This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

What does it mean to honor a fictional character?

I wrote previously about the parameters of acceptable loss … about what made the difference between a loss that I was willing to accept and one that I felt forced me to reload. I looked at the question in terms of comparing a lost soldier’s value as either a character or a pawn — their gameplay versus narrative value.

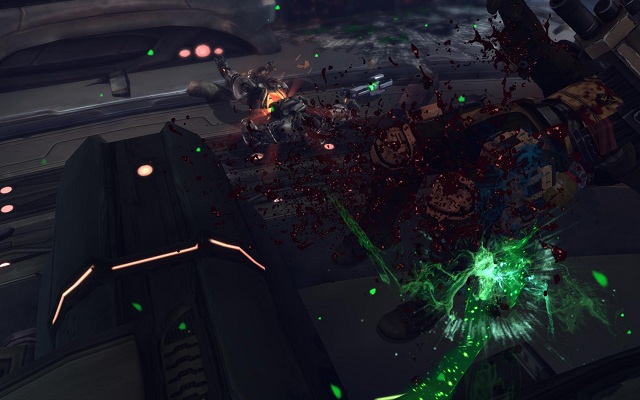

Recently, Tycho of Penny Arcade wrote about watching Gabe play Firaxis’ XCOM: Enemy Unknown, noting how if Gabe lost any soldiers, he wouldn’t “dilute their sacrifice with a reload.” But what does that even mean? We have some sense of what it means to honor someone, to act with respect, to keep your word, etc. But just how these ideas apply to fictional characters is not entirely clear.

One option would be to use the word’s other definition, as in honoring a contract to fulfill (an obligation) or keep (an agreement). If you view narrative as a kind of agreement between player and game in which the player agrees to suspend his disbelief and the game in return agrees to tell him a story, then this sense of honor applies quite naturally. To honor a fictional character becomes a matter of keeping an agreement: You don’t reload after a loss or play out of character because that would break the implicit agreement between you and the character and thus between you and the game. Breaking this agreement nullifies the game as narrative as if you decided to stop reading a book because you “disagreed” with the plot.

But that brings up an interesting point: Does it matter that these are characters that you, the player, have created and controlled? Not only are you made a part of the narrative and characters by setting your mind and imagination at its disposal, you are complicit in crafting it by your acts as the player. The question becomes not “What does it mean to honor a fictional character?” but rather “What does it mean to honor a character you have created and controlled?”

In a certain sense, it makes no difference at all. It doesn’t fundamentally alter the account given above of honor as keeping an agreement. If narrative is an agreement between player and game, this agreement is ultimately in some sense an agreement between the player and himself since the only enforcement of the agreement is the player’s own conscience. Thus, honoring a narrative is always, in some way, a matter of self-obligation.

But, although this doesn’t fundamentally alter the notion of keeping an agreement, it does complicate it. To honor a character you have created and controlled is really just to honor yourself and more radically than simply honoring a narrative. That character which you have created and controlled is you. You are the architect of his story. The crafter of his life and death. Thus, his sacrifice is your sacrifice; his stupidity is your stupidity (or more likely, your stupidity is his). Honoring him means treating him with respect and respecting his decisions and their consequences. And you do it because ultimately it means respecting yourself. You could reload and try again, but that would mean reneging on your previous commitments and ignoring whatever it was in you that directed those choices when you made them.

Which bring us back to the balance between gameplay and narrative: Changing your mind, rethinking your strategy, reloading, and starting again all make perfect sense with regard to gameplay. But as narrative, things get more complex: Those choices and that strategy are manifested in a character, an element of the narrative that is essentially the condensation of your choice that is positioned over and against you as the player. A simple reconsideration and a retry become something entirely different when you are confronted with a manifestation of those past choices that sharpens your concern for the narrative, which calls on you to respect the integrity of your own self in the past.

And this is why I believe games have the potential to be truly powerful aesthetic experiences. This is a new and different medium for the experience of the self and self-transformation. To be posed in your gameplay decisions against a manifestation of your past choices offers a powerful moment of self-reflection. Whether any games have yet made the most this is another question entirely, but the potential is fascinating.