This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

All right, quick-time events. You’ve served your purpose. Please exit the premises, or I’ll have you tased. Yes, that means now. Yes, Tasers hurt. A lot. How do I know? Well, I’ll tell you this: Never take your pants off when you’re — wait a minute; quit stalling. And stop crying. You’re embarrassing yourself. Look, you’ve had a good run, but let’s face it: You were a stopgap at best. No, you don’t get a severance package. Stop giving me the finger; it’s juvenile.

Best I can tell, game designers have used quick-time events in the same way that rednecks use duct tape. They asked themselves how they could best convey complex in-game cinematic moments in a way that still engages the player, and (after three beers and a hearty shrug) decided that a series of predetermined button presses at just the right moment could hold the whole thing together while they waited for a part to come in the mail.

Unfortunately, it took over a decade to get the part, and in the meantime, they had company over and had to make the duct tape look attractive, so they decided to draw some designs on it. Then they forgot it was there for a while, and by the time the part showed up, they’d already started doing meth and had completely forgotten what the damn thing was for and — OK, this metaphor seems to be getting away from me. Let’s take a step back.

I don’t know that quick-time events were ever intended to be a permanent solution, but they’ve certainly become pervasive. If you have a narrative-heavy video game, then by god you’re going to have some quick-time events. How else are players supposed to feel like they’re part of an interactive storytelling experience? Actually control it? Madness.

Not that we can really blame game designers. They’ve been grappling with the magnificence of their own creation. Utilizing a relatively new artistic medium to tell stories in ways never before told isn’t exactly a precise science. As graphics, physics, story quality, acting, control, and every other aspect of game creation has improved and evolved over the past decade, the delivery method for these cinematic moments has remained decidedly unchanged.

My reaction to quick-time events in modern games is akin to watching a prerendered trailer. The hero does amazing things that I’m completely incapable of doing once it’s my turn to guide the action. This disappointment was one of the very reasons I joined the masses in uproarious applause after seeing the first demo of Watch Dogs last May. I knew it was gameplay all along, but it wasn’t until the protagonist entered a car and sped off into the night that I realized Watch Dogs was a sandbox game. At any point the player could have veered off in a completely different direction, handling the presented situation in her own way. The inherent cinematic elements of the game would then turn those choices into something amazing.

Above: More amazing than dodging cardboard boxes by pressing “A”? Witchcraft!

Time is eventually going to make a fool of quick-time events (there’s a really bad pun in there somewhere). They served their purpose for a while, sure, but we seem to have broken through the barrier that was preventing us from experiencing in-game narrative in a truly unique way. We’ll have it all: The cinematic benefits of quick-time-event-driven experiences like Uncharted or Heavy Rain and the gameplay mechanics of a sandbox title. No more strings to hold us up. The player is left in complete control of the cinematic aspects of gameplay. The story will be written for us, but the nature and quality of the action will be a direct product of our play style.

And that would seem to be rub, wouldn’t it? To break the chains of Hollywood’s linear storytelling guidelines while utilizing its refined means of character conveyance. The story must be told to us, but we must simultaneously tell ourselves the story. We must control the actions and decisions of the character but not in such a way that completely derails a well-crafted tale.

Or at least be tricked into thinking that we’re in control.

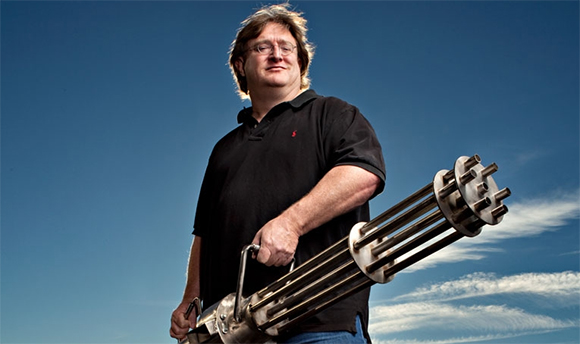

In February, Gabe Newell took to the stage with J.J. Abrams to discuss methods of storytelling in film and video games. In the midst of some awkward scripting, bad jokes, and clips of movies that everyone has seen and games everyone has played, there was one absolutely brilliant insight from Gabe Newell in regards to Portal 2.

We had to spend a bunch of time with the Portal 2 ending … to the point where not only did it seem possible that you could to shoot a portal to the moon but [that] it was the obvious choice, and yet the player felt incredibly creative for coming up with that as a solution … . When players are constantly trying to optimize, we give them a focus that allows them to isolate on the variable that we want them to optimize.

I felt clever when I shot that portal to the moon. There was no other decision to make, but for some reason it was my decision. Though, I do like Newell’s use of the word “allow” when speaking of manipulative methods of controlling the player’s decisions — quietly making us tell Portal 2’s story with our own hands. Still, this is a beautifully conceived, brilliantly executed replacement mechanism for the shoehorned monstrosity that is the quick-time event.

Above: You magnificent bastard.

Part of me can envision a world in which quick-time events still have their place. A world in which the iPhone generation saddles its withered, girdled frame to a dusty old 3D TV in the game room next to the ping-pong table and mindlessly presses square, triangle, circle, or x while they wait for that hot nurse to bring them their meds. They hope that their grandkids are coming for a visit today, but a combination of dementia and — “Ooh, look at that Nathan Drake and his toned buttox! Hey, Skyler! You remember the good old days when games were really games and not these brain-operated whatevs that the kids are using these days? Lawl!” Then their colostomy bag bursts. And while that might sound a little depressing, fret not: It’s pizza day in the commissary!

I just made myself sad. I’m going to go do something youthful and reckless while I play with my smart phone.