This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Dancing with the Devil of Dollars

It obviously isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that, not only do financial considerations influence a game’s structure and content, financial outcomes affect a studio’s likelihood of survival in the industry, based upon the machinations of its publishing overlords. Activision killed Bizarre Creations, Eidos ruined Looking Glass Studios, EA crushed Westood, Pandemic, Bullfrog, Origin Systems… well, the list could go on, until I turn a strange, purple color, but you get my point. And, when 3.4 million copies sold for a Tomb Raider reboot isn’t enough by a publisher’s standards, you can’t help but feel concern for a developer’s future.

It obviously isn’t beyond the realm of possibility that, not only do financial considerations influence a game’s structure and content, financial outcomes affect a studio’s likelihood of survival in the industry, based upon the machinations of its publishing overlords. Activision killed Bizarre Creations, Eidos ruined Looking Glass Studios, EA crushed Westood, Pandemic, Bullfrog, Origin Systems… well, the list could go on, until I turn a strange, purple color, but you get my point. And, when 3.4 million copies sold for a Tomb Raider reboot isn’t enough by a publisher’s standards, you can’t help but feel concern for a developer’s future.

But, if a publisher can kill a developer, outright, what do they do when in partnership? When elaborating upon the pitfalls of industry financing protocols, former Ubisoft Associate Producer, Yann Suquet, observes the two parties:

He goes on to paint a vivid image of the milestone system, a series of contractually-imposed objectives and deadlines, used by a publisher to encourage progress. Suquet notes two obvious problems with this arrangement. Firstly, a studio’s overheads don’t necessarily stack up with the revenue received from the publisher. So, if a hamstrung developer is strapped for cash, the publisher can capitalize, by withholding finances until certain milestones are amended or added. Secondly, it compromises a studio’s independence and creativity. This opens up the flood gates, allowing pushy publishers, who know little about game design, to assume control. Aside from this, artificial deadlines can potentially lead to a game feeling rushed, affecting content and/or quality.

In addition, an endless slew of, decidedly less than exemplary, deals continue to be struck behind closed doors, to this day. Many publishers seek to instill punitive regimes, deterring failure of any kind, by incorporating clauses into the contractual agreements of their development teams. Perfunctory, Metacritic score targets are a sorry sign of the times, recklessly brandished as a narrow-minded litmus test of performance, and a publisher’s underhanded means of depriving hard-working developers of their entitled bonuses and royalty payments. Shockingly, these arbitrary schemes are now mandated as part of the hiring process, by certain employers, and have been used as the cornerstone of publisher-developer negotiation, in condemning another studio’s work, to bring about more profitable terms and conditions.

And then, there’s the development time frame. We’ve all heard of zombified programmers, hooked up to IV drips of Red Bull, working their bloody fingers to the bone, and pulling unpaid all-nighters, just to meet the deadlines thrust upon them. A disillusioned spouse of an EA employee, Erin Hoffman, substantiated these concerns. In an online post, during 2004, she described the abhorrent working conditions, which sound not too dissimilar to that of a North Korean shoe factory, during a Kim Jong Un inspection; 12 hour days, 7 days a week, with no overtime, no compensation, no sick leave and no vacation, it’s astonishing that legal ramifications are not rife. It seemed the lid had been well and truly lifted, and a string of similar allegations were issued from other workers’ spouses, enrolled at Rockstar San Diego (2010) and 38 Studios (2012).

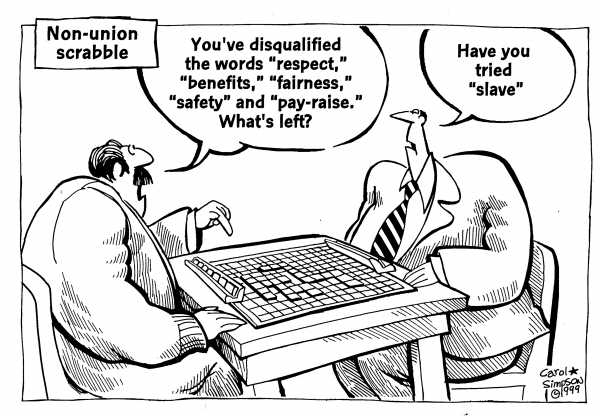

But, let’s face it, this reprehensible treatment is hardly surprising when considering game developers belong to one of the rare industries, which lacks union representation. The unsavory nature of this impugnable arrangement was unequivocally demonstrated when 100+ developer employees, who’d contributed their creative efforts towards the production of L.A. Noire, were surreptitiously excluded from the credits; this is an act, which violates IGDA Game Crediting Guidelines. However, no unions, no recourse.

It bears note, some of these issues may be studio-inflicted, whilst others may be publisher-inflicted. Professional employees are, quite understandably, unwilling to stick their heads above the parapet for fear of facing redundancy and litigation, which could materialize from prior signature of non-disclosure documents. Therefore, to date, these complications make it remarkably difficult to get an inside picture of the working conditions under some of the major publisher-developer partnerships. Recently, however, Hoffman asserts that conditions under EA have improved markedly; even if you’re no fan of John Riccitiello’s legacy, this is something to be proud of.

Indie developers don’t have the same restraints imposed upon them, as they are not in receipt of financial backing from a bunch of bean-counting creativity-crushers. Even when taking into account the introduction of Kickstarter campaigns, these low-key developers are beholden only to the consumer. In contrast, the so-called “publisher-developer” relationship has a tendency to drive a disconnect between the studio and the very people they should be trying to impress (the customer), as they, instead, chase the fleeting desires of their publisher. There’s no devil on the shoulders of the independents asking about multiplayer gameplay, set pieces or contrived plot devices and they’re able to freely explore all intended avenues, without fear of contractual barriers or threats of backing being pulled. They acknowledge a specific target audience and tailor their efforts to a niche area, rather than pointlessly branching out, in a vain attempt to generate “broader appeal”. Indie games are priced more competitively, and appear in a great many sales. On the surface, indie developers seem to display less greed. Take the Humble Bundle, where the customer purchases a selection of games and determines how much money they put in and its split between the creators, Bundle organizers and a chosen charity; consider this, since Humble Bundle’s inception, onlyone major publisher added their wares to an event (THQ), and only during a period of financial crisis.

[In Part II, we explore how overwhelming, publisher power stifles creativity and evolution of the industry, as well as the speculative development tactics, adopted by the big execs, based upon movie industry models, and the eternal litigation woes between publishers and developers]