This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Video games are only about 40 years young as a part of our cultural consciousness. They’ve gone through a lot of transitions that correspond with advances in technology — they’re really the only form of entertainment that depends so much on it that each new push forward is a “generation.” After decades of evolution, video games have become the multibillion-dollar, massive business it was always destined to be. It just took a while to get there.

“There” is the question, though. What is “there”? More graphics power? More investment money? More gameplay time? More polygons rendered? More buttons on a controller? Waggle sticks and people leaping around a room trying to get their onscreen avatar to dance? I’m still waiting for more blast processing.

No. “There” is the implementation of story, and, like games themselves, it’s experienced its share of growing pains. For years, games really didn’t have stories as much as they had concepts. You take an idea — say a robot guy with a blaster for an arm who has to fight other robot guys because the evil mad scientist is just an evil mad scientist — and build the narrative around that. Story was secondary because the design of the game was more important.

Expanding priorities

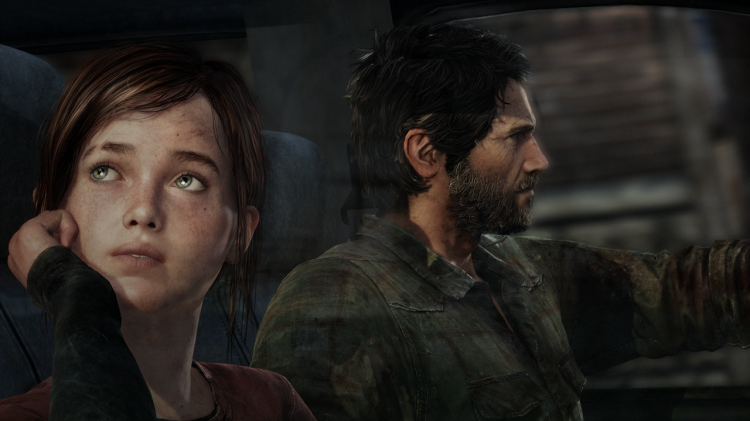

Above: Video games rely on technology to advance itself in how it expresses its artistry. The Last of Us is the apex of that evolution and shows what video games are capable of — not just high-concept stories but human ones. Ten years ago, a subtle and beautiful scene about petting a giraffe would have been unreasonable.

Years go by. Technology advances, and expectations rise through stronger stories in games — first with just text and basic character arcs, then with structure and plot twists, then cinematics and cutscenes, and ultimately seamless integration of all those elements into a new design where story is no longer secondary but primary. It slowly became the driving force of where game design would go over hours of gameplay, determining what was to happen and what journey the player would go on. After a good decade of current consoles building up to now, the twilight of another gaming generation, we’ve reached the culmination of all that effort: Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us.

Its story not only corresponds beautifully with the post-apocalyptic action-adventure game’s concept and design but also raises the bar — not for what video game stories “should” be but for what they can be as their own unique storytelling form.

For all that forward momentum of implementing stories into games, the stories themselves were often the problem. Many were convoluted, and developers couldn’t find a balance between pace and gameplay. Most were just poorly written because the people behind them were game designers first and screenwriters second. This past generation, we’ve seen it all elevate to great heights (and new lows), but all these stories were moving forward toward something. We just didn’t know what. It was like trying to think of the words to say when they’re stuck on the tip of your tongue. The Last of Us proves that struggle wasn’t for naught.

Higher standards

My full-time job isn’t blogging and tweeting about movies and video games or wondering why I’m still single. I work 40-plus hours a week in the film and television racket and have for years. It’s fine — pays the bills. It’s not exactly what I thought I’d be doing when I was 12 and reading back issues of Detective Comics and dreaming of inventing cool gadgets and designing awesome mansions with secret caves, but it helped me find an outlet for creativity.

With this job, I read a lot of scripts. Some good. Most bad. My apologies to those who ask me to read them, but some of these scripts make you wonder how bad movies get made at all when the bad stuff rarely gets past some low-rung ladder-hopper like me in the first place. In terms of ratio of bad writing to good writing, it’s 99 to 1. The deciding factor could simply be bad dialogue, unclear action, bad pacing, an idea that’s probably hard to sell, or just an overdone plot to the point of you saying, “Oh, another one of these.”

The Last of Us is good writing. It’s a good video game first, but it wouldn’t be nearly the masterpiece — yes, that’s a word I’ll be using, so deal with it — that it is if not for the writing. Smart writing, clever writing — writing with a humanistic angle rarely seen in a video game, a medium dominated by dudebro gun-toting and anime-action sword-swinging because when you’re a medium this young, mindlessness is the easiest thing to do. Video games have tried so hard to be entertaining and “cool” that they’ve neglect the fundamentals of good writing over the last 40 years trying to find themselves. The Last of Us shows you don’t have to try so hard. You don’t even need to try all that hard to be original. You can take a risk. Instead of being broad with one too many parts to keep track of, The Last of Us uses simplicity, boundary-setting, and familiarity to explore the best parts of its character and theme.