This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

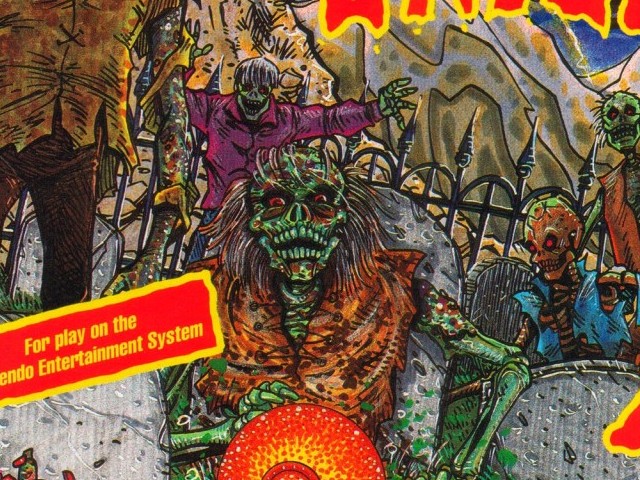

Haunted House

“… ATARI is unlocking the entrance to the HAUNTED HOUSE and letting you test your bravery. Do you dare enter the frightening old mansion? If you do, remember to carry matches; the HAUNTED HOUSE is very dark.”

The Atari 2600 was home to one horrifying game, which you can play over at Virtual Atari.

This was a top-down game set within a series of connected rooms with stairs leading to additional levels. The only thing representing you were a pair of eyes floating in the darkness. Matches lit up the area around them for a time and revealed hidden things, such as the three pieces of the urn that you needed to find and escape with.

You also weren’t alone. Critters like bats and spiders infested the old house, and a ghost could follow you through walls. Whenever you got close to one of these monsters, the wind would begin rising in crescendo, blowing out your matches. Contact with any of them unleashed a storm of effects like flashing walls and spinning eyes that took one of your nine lives.

Score was measured by how many lives were left and how many of the infinite matches you went through in trying to piece together the urn. There was also a scepter you could use for protection, but since your inventory could only hold one item at a time, you had to decide whether to chuck the urn pieces you had for it or not.

The horror came from the special effects. The rising wind, the monsters, and the ear-ringing thump of bumping into walls (higher difficulties made them visible only by using matches) all added to the subtle chill of exploring the place as if the light show after touching a monster wasn’t enough to shock your nerves.

Haunted House was one of those early titles that broke down the basics of what made a horror game tick, and it did it well. A lot of the concepts it touched upon back then have since found their way into many others, from Infogrames’ Alone in the Dark to Frictional Games’ Amnesia: The Dark Descent — two games that took that simple theme and ran wild with the possibilities that advancing technology made possible.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DZHnObwgGA&w=420&h=315]

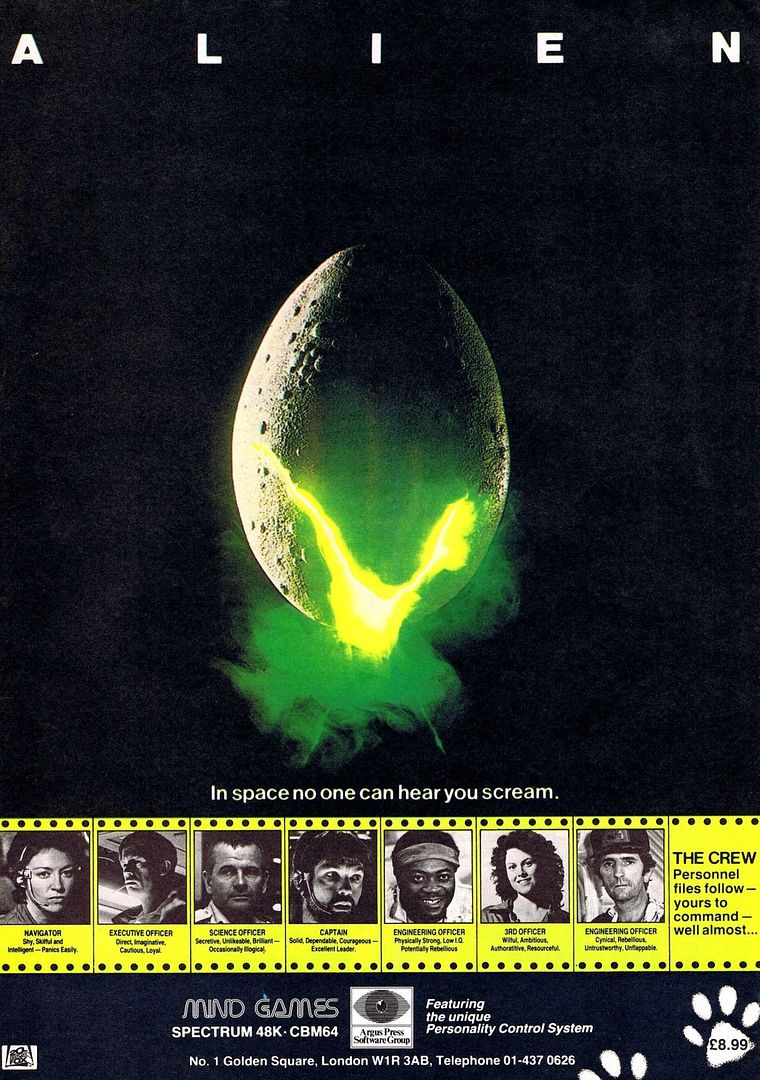

Alien

“In space, no one can hear you scream.”

Though the Atari 2600 got its own Alien game in 1982 as, oddly enough, a Pac-Man clone (which you can also play over at Virtual Atari), PCs would get a more tactical version two years later that put them in command of the Nostromo ship crew. You were the boss!

That also meant that the fate of everyone was in your hands, which left the opportunity open for you to try to change things.

To make it more interesting, the game randomly chose which character would be the murderous android protecting the alien. It could be Lambert. It could be Parker. It could even be Ripley. You just wouldn’t know until you started playing.

A “Personality Control System” also gave each crew member his own reactions. Dallas might not want to go into the next room for whatever reason even if you tell him to go in there to pick up Jonesy’s carrier.

At the same time, you could also alter how events actually played out from the film. Why use the shuttle when you can corner and then eject the alien out into space from the Nostromo instead?

So how about scares? The real worry was wondering which crew member was the android and where the alien may pop up next, making up for the lack of visual surprises and menu-driven, top-down gameplay.

Three levels of the Nostromo could be explored, and the alien kept moving about to keep players on their toes. All the while, oxygen slowly bled out, creating a time limit that you had to be vigilant in watching.

The scares didn’t jump out from a closet as much as they wormed their way into the chill creeping up your spine while wondering what was going to happen next. In a way, this could even be seen as one of X-COM’s early ancestors from a tactical perspective — a crew of bodies facing the unknown with their virtual lives hanging on whatever decision you make. And sometimes, that’s terrifying enough on its own.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzWDT_cwuTI&w=420&h=315]

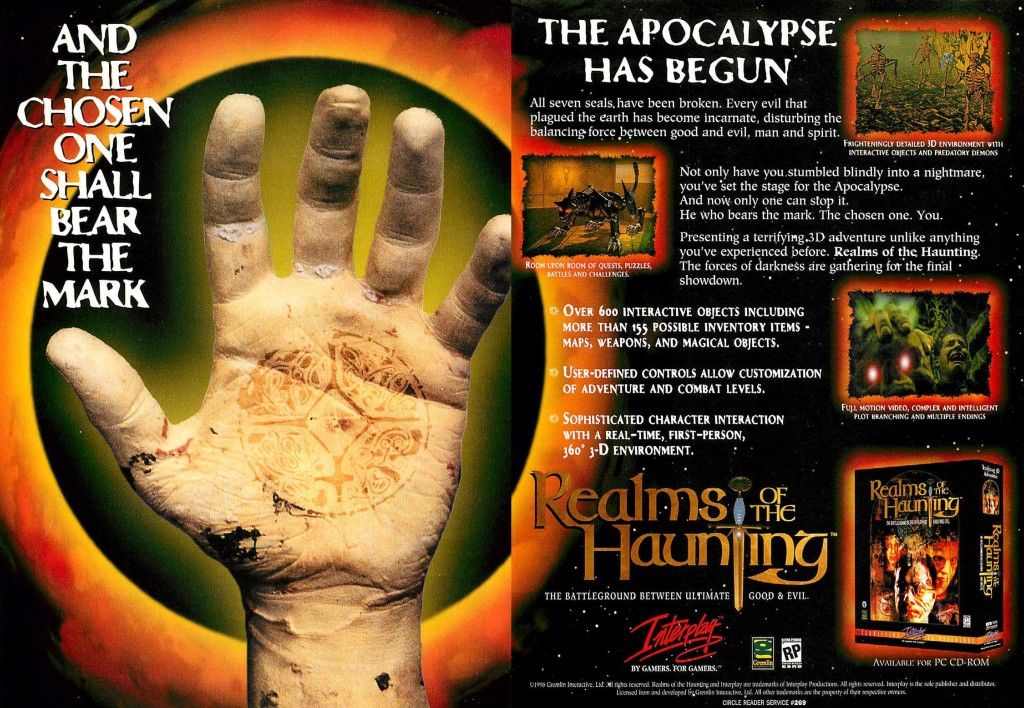

Realms of the Haunting

“Realms of the Haunting is a disturbing vision of the future, based on the many beliefs of the Apocalypse. The horror in Realms is the underlying fear of the end; the collapse of light and the dawn of a new age of darkness.”

An often overlooked gem is Gremlin Interactive’s Realms of the Haunting from 1996. This was a big CD-ROM game that blended both full-motion video shots of live actors against CG sets and backdrops. It came across like a first-person adventure game, complete with an inventory for items, clues, puzzle-solving, and whatever else wasn’t nailed down. Later, it felt something like a first-person shooter with slightly clunky controls.

In the game, you play Adam Randall, who arrives at his father’s mansion to see to his affairs now that his father has passed on. The problem is that what he finds only adds to the mystery of how he actually died — and what he was involved with.

The player later discovers that the house is sitting on a nexus of worlds and is where the balance of the cosmos will be decided. It’s like the movie Poltergeist, but instead of a house built on an ancient burial site, the mansion is sitting on top of a piece of Planescape.

The miniature manual laid out the mechanics on how to go about your investigation, along with a small tutorial walkthrough, but the majority of the lore shoring up the arcane backdrop and terror of Realms was within the game. Reams of text described the objects you’d pick up, revealed what was written on forgotten pages, and subtitled the ranting evil issuing forth from vile maws.

Creepy doors, curious paintings, darkened hallways, and the first encounters with evil beasties with little to fight them with made for a few harrowing early hours until Adam began growing his arsenal. As the encounters became more commonplace, Realms went from being terrifying to more of an action-adventure set within the nightmare of a potential apocalypse.

Story-wise, the game didn’t subscribe to specific belief systems in sewing up its backdrop, instead basing its narrative on an abstraction of the cosmic battle between “good” and “evil” and the reflections of their struggle seen in angels and devils. The writing and characterizations grow ever more arcane in their twisted strangeness the further the player progresses until the final curtain. For a game that used a lot of FMV, it didn’t do a half-bad job with what it had — especially casting-wise.

The good news is that Realms of the Haunting is actually available on Good Old Games. Though the graphics are a bit dodgy by today’s standards and the lack of a more extensive control-customization scheme can make getting around a little iffy, Realms of the Haunting’s metaphysical and multiversal mega battle between forces beyond our ken brings enough horror and adventure to make this haunted house worth visiting.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xSM7K23djU4&w=420&h=315]

(These were drawn from a small series I did last year on my blog, World 1-1, that explored horror games of the distant past.)