This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Ah, division, that inconvenient wind against the illuminating candlelight of concession. The game industry is full of it — conflicting philosophies, differences in taste, ideologically driven claims of right and wrong. Everyone has the ultimate truth, it seems.

Fittingly, certain games become that very line in the sand, one recent example being “Gone Home” by The Fullbright Company. Some lauded it as a cutting-edge take on gaming narrative (wrong), while many others condemned it as a potential threat to traditional game design (also wrong).

Despite all of the noise, one thing is certain: Games like Gone Home are unconventional. And while I don’t see such experiences as being inherently valueless, I’m compelled to analyze them with regards to the other mechanically driven titles in the same vicinity.

My conclusion: The Gone Homes, Dear Esthers, and Kentucky Route Zeros of this medium are fragmented experiences in comparison to countless others with similar qualities…plus more.

Some people I know will be pissed if I don’t mention this game, so…

The false negative

“It’s not a game” has become a somewhat common form of criticism regarding interactive entertainment that goes a bit light on interplay. It doesn’t take much effort to understand why this is used, particularly against titles that share a space laden with mechanically driven games. In all directions of the Steam store, you’re faced with numerical systems, puzzles, ball-numbing action, spreadsheets and/or micromanagement, and all other manner of technical frivolity. Occasionally, though, stands a ‘game’ that pitches itself as a “nonviolent and puzzle-free experience” (taken straight from Gone Home’s store page).

Of course this would raise a brow or two. What such skeptics don’t understand, though, is that claiming the absence of a particular quality or state as a negative is a logical fallacy with no value to artistic critique. If one attempts to fault Dear Esther because it’s nothing like a traditional game, one must then apply that same criticism to, say, the film “Eyes Wide Shut.” But of course nobody would do that, because they would look really, really stupid.

“Not a game” is irrelevant regarding the intrinsic qualities of an individual piece of art. It has no real meaning or purpose until it’s explained further and given substance. Those who use such a criticism obviously have a greater point to make, so it’s better to identify what absent qualities leave an “environmental storytelling experience” desiring more, and, most importantly, WHY those absent qualities leave such an experience so bare-assed.

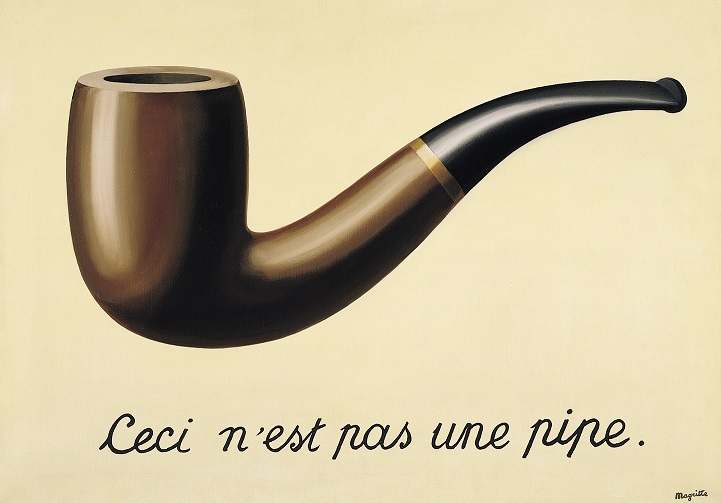

Actual smokers gave this a 2 out of 10.

Cars become scooters

When comparing the descriptions of such divisive games, one finds similar language used. “Explore incredible environments,” reads Dear Esther’s list of key features. “The Stanley Parable is a first-person exploration game,” reads another. Kentucky Route Zero: “A focus on characterization, atmosphere, and storytelling rather than clever puzzles or challenges of skill.”

OK, I’d say the writing is on the proverbial wall. These games are about plopping the player into an environment and having them decipher a narrative based on expositional facets of that setting. But, all things considered, what games DON’T do this nowadays? If you play any title with some small emphasis on adventure, characterization, and/or setting, you can almost guarantee that an element of environmental storytelling is going to be featured.

A close and objective look at games like Dear Esther reveals mere pieces of greater experiences. To get something like Gone Home, you simply must strip an average game of mechanics, artificial intelligence, character modeling and animation, and any form of governing system/s linking all of those together. In the end, your final product includes the simplest aspects of design — voice acting, written narrative, hard-surface modeling (the easiest to learn and achieve), and so on.

The Greenbriar home can have a secret door, but not a little puzzle to open it? How contemporary.

Anything you can do…

The usual counter: “Games that emphasize but a few of the medium’s many features can place more focus on them, effectively doing them better.” Well, not exactly. Time and resources do not directly correlate with quality and effort. “Star Wars: The Old Republic” was a bloated, narrative-driven commercial mess that became nothing more than a punchline amongst seasoned MMO players. Quantic Dream games are not candid about their emphasis on writing and storytelling, yet the resulting quality is often tepid and, well, pretty hilarious at times.

No, the fact that Gone Home, Dear Esther, The Stanley Parable, and Kentucky Route Zero place the bulk of their focus on specific, basic facets of the gaming experience does not, in any sense, mean they can or will do them better. Environmental storytelling has been common in video games for decades now, and it’s not only treated as a complimentary side next to its main course (gameplay), but the two also often work hand-in-hand, making the overall result arguably more unique, gripping, and impactful than the limp “walk here, listen to this” approach of the aforementioned.

When interactivity becomes the baseline standard, you get an empty, lifeless family home with written notes and quaint 90s paraphernalia to inspect. When it’s an additional context to the technical aspects of gameplay (your abilities as the player), you get Adam Jensen’s apartment with exposition referring to his traumatic mechanical transformation…or disfigurement, as he sees it.

Environmental storytelling is one of many tools that developers use to provide information and unveil the player’s world. One could go on for days listing specific examples, and so I have little doubt that anyone reading this can instantly think of their own.

Can I introduce you folks to Fallout: New Vegas – Old World Blues? (Stay away from Dr. Dala…)

For its own sake

With all of that said, I must clarify one important thing: I do not, at all, believe that what “environmental storytelling experiences” lack in relation to traditional games instantly qualifies them as bad. Incomplete, sure, but if what they are attempting to accomplish is done in a skillful, admirable manner, then they certainly deserve some kudos. Kentucky Route Zero owed itself to be the best it could be with what it had, which is exactly why I quite enjoyed it. Nonetheless, despite how good it was individually, a part of me felt something was missing.

Many people dislike these types of experiences for a reason. The term “game” was not invented along with this medium; it’s use and relevant qualities stem back thousands of years, from what we’ve managed to dig up. It’s meaning and qualifications are not going to change overnight, particularly at the existence of “Read the Letter” by Indie Studio #841.

We all were drawn to this hobby based on specific factors, and many of those are now expected standards within the medium. It should then come as no surprise that gamers sometimes assume they’re not getting the full potential experience when those elements are missing.

This is not, I repeat, NOT a game concept. It’s a story idea. You would not pitch this to a publisher. Sooner or later, people need to learn the distinction.

Mechanics make the game; they always have and likely always will. They are all of the little details that cannot be found or experienced in any other form of entertainment, and they are likely the reason you picked up a controller or grasped a mouse in the first place. Sure, other factors impressed you equally along the way, but that’s always been icing on the cake, has it not?

Storytelling is not foreign to art, overall. It permeates virtually every other medium, and so it stands to reason that an emphasis on such only forces something so unique as gaming to blend in with the rest. Narrative is not a problem by default, but it becomes stifling when it’s placed before that which is inherent to video games. To deprive any game of mechanics in favor of forced sentiment or “meaning” is to effectively strip it naked.