This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Author UnSubject over at his blog, Evil As A Hobby, scrubbed through video game labeled Kickstarters spanning 2009 – 2012 and assembled the data into a compelling look at the extremely low rate of follow-through made by over 366 projects. It’s a great article that has encouraged quite a bit of discussion both there and across the ‘net.

It’s a revealing look at something that I could only touch on in the end summary to my survey of 2014’s gaming landscape on Gamesbeat – a disturbing implication of completely missing release estimates by Kickstarted projects based on only a tiny sample of reported releases slated for 2014. UnSubject’s exhaustive work not only nails home what I could only assume, but encourages discussion on just how successful hundreds of other projects have been in the past few years as part of a bigger picture.

UnSubject has also made the data available for everyone to look through and being interested in crowdfunding, particularly the ramifications of what Kickstarter and Steam’s Early Access have created for developers, I took the opportunity to explore a question posted in a comment to UnSubject’s original article by another writer, Odious Repeater, and one which I had also been curious about as well: does experience matter?

It’s no secret that experienced game developers, both indie and commercial, have used Kickstarter in the past and are continuing to do so today. But how well have they actually fared against teams or indies with little to no game development experience?

Definitions

The first problem was in defining what that experience was.

Because gaming, particularly electronic gaming, is still relatively young as a creative medium, terminology hasn’t quite developed at the same pace (just look at the debates over RPG definitions). I didn’t like having to use the term “inexperienced” which I felt has too much of a negative connotation to it. Instead, I’ve opted to define such teams or individuals as being new to development.

The next problem was just what that experience entailed. Is it having made one flash game? Or is it having made a dozen over the years for free? Does commercial success make a person experienced over a team of a fans that can code a game from scratch as a tribute to a classic title? Is it the resume-defined version of having X number of years and Y shipped titles?

The definition of experience that I used started with the following conditions:

- the developer has to have created and made available a complete game to the public; medium doesn’t matter aside from it being a video game of some kind

- said game has had to have been recognized by the public (such as being recognized at the IGF Awards or by a major outlet such as here on Gamesbeat, Gamasutra, Gamespot, etc.. or through popular acclaim) or has been made commercially available

Individuals/teams were automatically considered ‘experienced’ if they had the following:

- if the individual(s) has had experience at a major game studio

- if the individual(s) have aided or have produced a commercially available title

- if the individual(s) has had a long career in a field related to game development (such as having been a coder for several years)

The reason I had stuck to these set of requirements was to filter out situations where an individual may have created one Flash game years ago that no one had ever heard about.

If a Kickstarter had also claimed experience, I also had to be able to independently verify that experience using the information given to me in the same pitch that everyone else will be reading. If I couldn’t verify it, I couldn’t count the project.

I’ll be the first to admit that this isn’t a perfect definition. As Odious Repeater has also pointed out to me, the question of how that experience is spread out inside a team is also important food for thought that could impact a project in critical ways.

With that said, let’s take a look at what I could pull from UnSubject’s meticulous research to answer the question of just how much experience factors into their Kickstarter project data.

How many Projects

Based on the premise of UnSubject’s data, we’re looking strictly at successfully funded video game related Kickstarter projects launched in the years covering 2009 on through 2012 for a total of 366 projects.

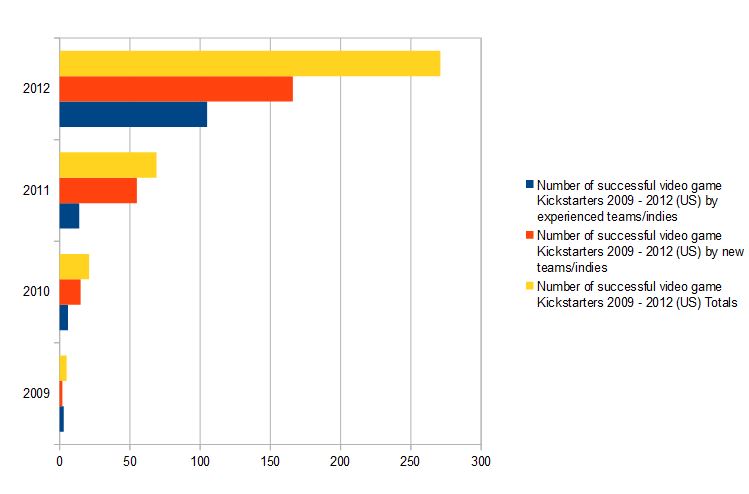

The chart above separates the projects into three categories per year. The yellow bar indicates the total projects, the orange shows the number of those that were launched by new indies/teams, and the dark blue stands for projects by the experienced teams/indies.

The actual numbers look like this:

Given Kickstarter’s initiative as an crowd funding enabler for new teams and independent projects, this shouldn’t be too surprising to see such projects outnumber the “veterans” with 2009 as an exception.

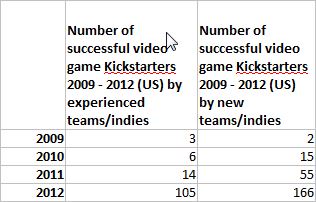

Cash flow also tells an interesting story:

Teams boasting some experience or popularity based on their previous work still pulled in a respectable share of donations with new teams/indies beating them in 2010 and 2011, likely because they had the most projects for backers to throw more money at. In 2011, 14 funded projects were launched by experienced teams competing against 55 launched by those without experience, for example.

But 2012 saw a major money shift. That’s arguably thanks to the focus on the massive success of Double Fine’s project and the Ouya Kickstarter later in the year.

At the same time, the argument could also be made that seasoned teams would still have found the same degree of success given time. This is borne out by sixteen experienced projects with a number of well-known names behind those as well posting over 500k in donations following Double Fine’s. Even if we took out Ouya’s and Double Fine’s Kickstarter numbers, experienced teams/indies still had drawn in almost roughly 3x as much cash in the 2009 – 2012 period versus those just starting out ($26,609,622.94 vs. $9,574,700.01)

Finally, successful Kickstarters by experienced indies/teams saw a nearly tenfold increase to a total of 105 such projects in 2012 versus only 14 in 2011.

Also interesting were how many projects allowed for external funding options, such as Paypal. Out of all of the experienced projects, 22 opted to support that initiative versus 15 for new devs.

Completionist

So how do Kickstarters seasoned with experienced individuals fare against those just starting out?

Let’s take a look at a few charts below:

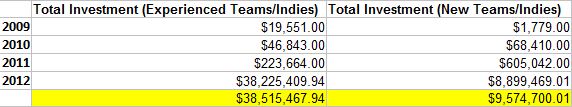

Here, we’re seeing that, to date, only 40% of those projects with experience have been completed. On the other side of the coin, 13% have been released in a partial state which can include Early Access on Steam, an ongoing “beta”, or as “Part One” with subsequent releases to arrive later.

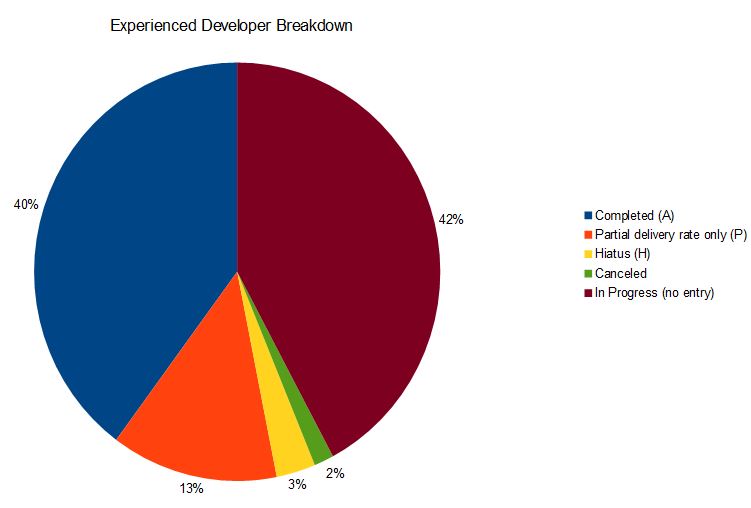

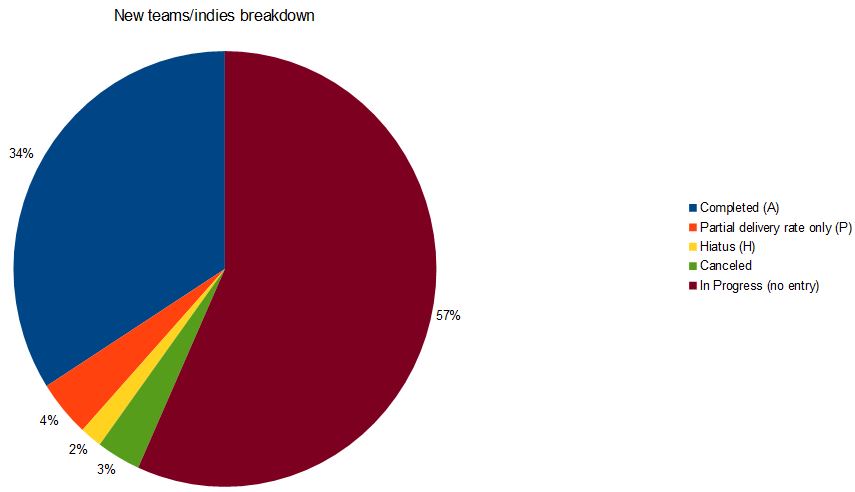

Compare the results above with those from new devs:

Highlights include seeing only 34% of those projects launched by new teams/indies having been completed to date. A whopping 57% are still in progress. An interesting point is that only 4% of these projects have released a “partial” game in lieu of a complete one versus the 13% in the experienced camp.

The charts appear to indicate that veteran developers have the edge in completed projects as well as releasing partials to satisfy backers and garner additional income via initiatives like Early Access. But breaking down the numbers is a bit more revealing.

For one, new teams/indies continue to have the lion’s share of projects on Kickstarter resulting in higher numbers in nearly everything else as noted earlier in the bar graph above. Let’s take a look at a few of the numbers bearing this out:

- Compared to the 128 that belong to the experienced camp, new developers have launched 238 projects.

- For the 51 projects that experienced teams have technically completed, those starting out have 81 in the same category.

- Experienced teams have 54 projects that are still in progress versus new developers who are busy working on 135.

So while the percentages skew things towards experienced devs, the actual numbers can argue that newcomers are busy on a much larger range of projects with more releases.

Pitch Quality

A common theme for both camps is that regardless of experience, creating informative pitches continues to be a problem for both potentially misleading investors. It’s a topic Odious Repeater had touched on in an article they had written last year which digs deeply into breaking down a number of the unrealistic expectations, and inherent dangers, of Kickstarters focused on game development. Of particular interest are some of the hidden costs that adversely affect the final output of any one project — it’s not all fun and games — which Haje Jan Kamps has recently written about here on the topic of backer rewards.

Projects that have had professional artists, not necessarily game developers, as part of their push have also often had the most impressive looking pitches. That should probably be no surprise, yet at the same time, the lack in mentioning other disciplines such as programmers, hard designers, managers, etc.. that normally would accompany such a project is also pause for thought.

Conclusions

So does experience matter?

The data presents a compelling argument that it brings a certain level of professionalism enabling, at least percentage-wise, more projects to completion or partial release although the breakdown paints a more nuanced picture. I can’t speak to the quality of the final products, but it’s safe to guess that an element of that experience is in knowing how to build an efficient production pipeline process right from the start. There is also the factor of being able to work with fellow developers that may have shared similar working experiences over many years.

Scrubbing through the projects myself also affirms the notion that having experience isn’t necessarily a guarantor of success or product quality, especially when the results can wildly vary.

I’ll also re-iterate UnSubject’s warning – investing in Kickstarter is a risk.

If you can’t stomach the thought of potentially losing money on an investment, it’s probably not for you. Experienced and new developers have both canceled projects or have yet to deliver on their promises after several years of development as the above charts and UnSubject’s original findings bear out. Last year, The Daily Dot ran an article covering findings showing that only 25% of tech and design Kickstarters delivered on time.

The biggest lesson for anyone thinking of investing in a Kickstarter project is in whether those launching the project have provided enough to go on, realizing the risk involved with the scale of their projects, and then choosing to invest accordingly — or opting to wait for the final product and contribute to it by buying it on the day of release.

I still believe in Kickstarter as a valuable crowdfunding option for developers weighed with the understanding that it’s still a gamble, at least as far as release dates and the final quality of the project is concerned. But blind faith is no excuse for not doing your homework, no matter how much experience any one project may have on their resume.

(Full disclosure – This article was originally published at my blog and has been edited for clarity and additional information. I have backed Kickstarter projects. The data for the following article is based on UnSubject’s original data. My worksheet with the new variables and my final numbers is located separately here.)