The microchip computer was, arguably, the most significant invention of the latter half of the twentieth century. The closest preceding innovation to provide humanity with such a large opportunity for intellectual advancement was the printing press.

Computers have redefined every aspect of human life, from how we communicate and do business to how we study and explore our universe. In just a few years, we have moved from telegraphs to video conferences; from the first manned flight to sending robot rovers to Mars.

Despite the depth and complexity of the problems computers are tasked to solve, the general populace expects them to function with the simplicity and ease of a household appliance. Consumer demand for computing simplicity is so strong that Apple, the most valuable computer hardware and software company on Earth, has centered their entire public image around the slogan, “It just works.”

Over the last decade, popular perception of computer technology as more servant than tool has grown stronger. In that time — even as computers and electronics have become a larger part of our daily lives — worldwide Google search interest in the Computers and Electronics category has dropped by more than fifty percent.

The category’s top search terms in 2004 included “Linux,” “drivers,” and “Java” with rising terms such as “Sasser,” “computer worm,” and “Eclipse,” a software development environment. Last year’s results tell a vastly different story with top terms like “Apple,” “Google,” and “Samsung” and rising terms “Galaxy S3,” “Minecraft,” and “app store.”

The rise in adoption paired with a decline in comprehension presents a major dilemma for software companies: How do you address public demand for short learning curves and simplified experiences while performing increasingly complicated tasks? How do you manage a product that hinges as much on client perception as it does on technical reality?

As tough as those questions are to answer, the situation is even more daunting for engineers inside these companies. They must not only deal with this client demand, but also with the opinions and wants of their non-technical co-workers who are members of the “it just works” demographic. These employees often shape the direction of the product yet rarely understand how things operate under the hood.

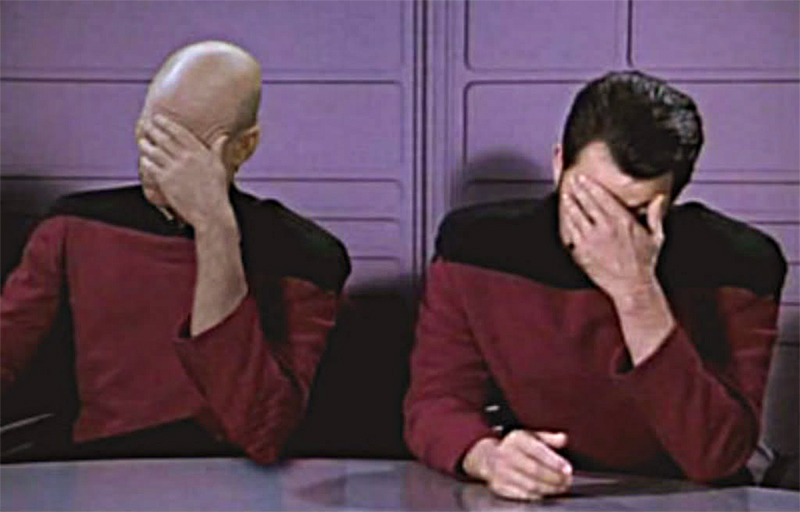

Any experienced software engineer or systems administrator can regale with seemingly endless tales of technical hubris from producers, sales directors, or C-level executives. The clichéd “disgruntled programmer” is often just tired of being told that one plus one equals three, especially when he was hired to do calculus.

It is difficult for anyone to be told how to do their job, let alone by someone with little understanding of the tasks involved. This is the world software engineers at small to medium-sized companies live in, where the relationship between sales and engineering is rarely buffered by project managers and a CTO.

With rapidly changing technology now ubiquitous, understanding the latest devices and the methodologies behind their use is culturally perceived as a sign of both youth and intelligence. Delegation of skilled tasks by unskilled leadership is a common problem in any business, but it is an epidemic in a software development space where executives are constantly urged to be ahead of the curve.

Compounding this problem is the unspoken yet universally acknowledged truth that many people drawn to technical professions are not very adept in social interaction. Though they may be unable to constructively express their frustration, it does not mean that it is unjustifiable.

A popular stereotype among non-technical employees of software companies is that programmers say no to everything. While anyone has the capacity to be negative and stubborn, more often than not this behavior from engineers is a direct response to illogical feature requests or unreasonable time constraints.

For example, here are some actual feature requests that I have either witnessed or have been expected to personally deliver, some with threats of termination if they were not accomplished:

- Modify the source code of the Google Analytics platform to meet the company’s tracking needs.

- Secretly and automatically install a native application to a smartphone’s desktop when a user hits the company website.

- Triangulate a user’s position to less than one meter accuracy, via cell phone GPS, while they are inside of a building.

- Match Playstation 2 graphics quality on a first generation Nintendo DS (PS2 can render 75 million polygons per second, while the DS can only render 120,000).

It is irrelevant that the executives who made those requests did not understand why they were unreasonable. The problem is their failure to heed two principles that can be found in any book on leadership or management:

- Be quick to ask questions and slow to offer solutions.

- Avoid micromanaging at all costs.

As it is with any type of business, the best technology managers assist teams of skilled employees in finding their own solutions to both internal and external problems. Ask a software engineer what they enjoy about their job, and the answer will probably include something about problem solving.

In order to drive a development team towards productive results, an experienced software manager might reformulate the previous requests in a way that allows the engineering team to visualize potential solutions.

- “What can Google Analytics do, what are its limitations, and how can we meet our tracking needs if it’s not enough?”

- “We need to increase our app’s circulation. Let’s brainstorm some ways to do that.”

- “What are the best results we can get from a cell phone GPS and what are some ways we can improve the accuracy of triangulation?”

- “The client is not happy with the graphics quality on the DS. They want it to look like the PS2 game. How close can we get it and what are some technical details I can relay to them?”

Stepping back from your personal investment in a project and deferring key product decisions to your engineering staff can be difficult, but it is essential to growing and maintaining top tier software teams.

After all, no one has ever been hired to a skilled position because of their lack of ability. The best managers know that the fastest way to motivate a team towards results is to exhibit trust in them. As the poet George MacDonald said, “To be trusted is a greater compliment than being loved.”

Blake Callens is lead engineer for mobile e-commerce platform SpotTrot, which powers stores for many of the world’s leading entertainment brands, such as Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber, and Sesame Street. Blake is known for his contributions to e-commerce technology, especially within the realms of computer vision and natural user interface UX. He was lead architect and co-inventor of the DEMO-winning Webcam Social Shopper, is a Webby award winner, and is co-inventor on e-commerce based U.S. Patent 8,275,590 for virtual dressing rooms. If you would like to connect with him, follow him on Twitter.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More