This post was written by entrepreneur Dan Shapiro.

This post was written by entrepreneur Dan Shapiro.

Everyone knows of the mythical elevator pitch. You find yourself in an elevator, rocketing towards the penthouse suite of a downtown office edifice, when you realize that the person standing next to you is a powerful and influential investor. She asks what you do, and you calmly deliver your pitch. Just a sentence or two, properly chosen. The doors open, the conversation continues, the IPO is near at hand.

I’m here to tell you that the elevator is real. While you may not be trapped in a small ascending room, the potent entrepreneur’s life is full of inflection moments: brief opportunities to shift the destiny of your company. And a proper pitch is essential to take advantage of them. But contrary to what you might have heard, the solution isn’t the 60-second elevator pitch. In fact, the elevator pitch is only a simple, basic example of a much more powerful tool: the Pyramid Pitch.

The Pyramid Pitch is based on a simple and fundamental principle: Startups are dictated by randomness and chaos. Sometimes this is obvious, as in the elevator case. Other times the situation appears controlled, for example when you have five minutes allocated to speak at a pitch event. But minds wander, distractions beckon, bladders fill … if you don’t grab your audience immediately, you may never get them back.

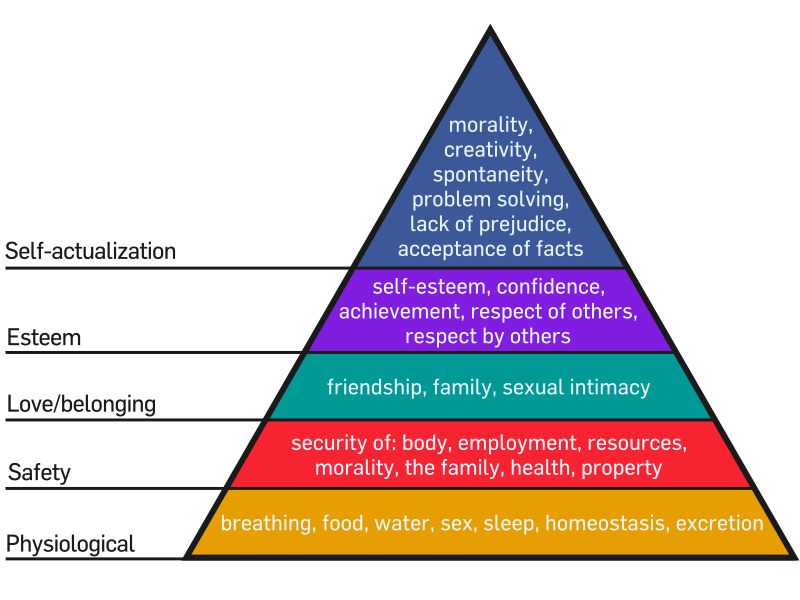

The Pyramid Pitch draws its name from Maslow’s famous hierarchy. Maslow postulated that humans had many “needs,” but some were more fundamental than others. Until fundamental needs like food, water, and excretion were met, people would not be able to strive to achieve needs that were higher in the pyramid, like morality, spontaneity, and self-actualization. Or, as I like to think of it, it’s hard to attain enlightenment when you have to go to the bathroom.

So the concept is simple: when you pitch, deal with the most urgent matters first. What those are will vary by company and by listener, but let me give you an example from my first startup, Ontela. Ontela was founded in 2005, as the notion of including a camera phone was just taking off. It was two years before the launch of the iPhone, and at the time, people were just starting to come around to the idea that a camera on a phone was more than a gimmick. Here was the top of my pyramid pitch. It would usually start with someone asking me what we do.

Ontela makes it ridiculously easy to get pictures off of your camera phone.

This is the first line of the pitch. It addresses the most urgent and pressing matter in the investor’s mind at this point in the conversation: “Do you do something that I find the teeniest tiniest bit interesting?”

Today, 74% of people can’t get pictures of their phone. With Ontela, you just hit the shutter button and the picture appears on your PC in less than a minute.

There are now two possibilities. The first is that the conversation has been brought to an abrupt halt by something like “That sounds fascinating but I only invest in clean tech companies”; “Oops this is my floor”; or “申し訳ありませんが、私は日本語を話す.” The second is that they are thinking, “OK, how do you do that?”

We license our software to wireless carriers who include the software on your phone.

Again, two options: They say sayonara, or they nod agreeably and start wondering what the actual business looks like. So you explain to them the most important thing: distribution. In this case, through the wireless carriers.

The service is free for a month. Then, it prompts you to subscribe for $2.99/month to continue using it.

If they made it this far, things are going pretty well, and they’re probably wondering about how we (and by extension, if they invest, they) are going to make money.

The pitch goes on from there, but the philosophy is incredibly simple:

- The most important stuff goes first, and

- If you stop at any point, they walk away with a solid idea of what you’re doing.

This may seem simple and obvious, but I’ve seen too many people mess it up. In fact, here are three of my favorites bad pitches.

The story pitch: They lead off with a five-minute backstory on how they thought of the invention, how they met their cofounder, or why they care so much about this business. Sometimes this is appropriate – like when you’re seated next to someone at a dinner, and you know the story’s good. But it’s usually the wrong move. First, because you get cut off, and now they know about your college DJing business but have no clue what your new company does. Second, because they zone out hoping you’ll just get to the point. Third, because if you’re not a great storyteller (and it’s not a great story), this will backfire terribly.

The business plan pitch: They lead off with market sizing, competitors, and business case analysis. Great for your second meeting, not so good for an introduction.

The feature pitch: They start rattling off a list of all the nifty things their product does. This is a great way to say to your new friend with the crossed arms and distracted smile, “I may ignore strategy for tactics, but at least I’m deaf to social cues.”

The disease is sloppy and meandering pitches. The solution is the Pyramid Pitch. Just remember: Think about your audience. Respect the random hand of fate. And happy pitching!

This post originally appeared on Dan Shapiro’s blog.

[Top image credit: StockLite/Shutterstock]

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More