What if LucasArts never existed? What if the irascible filmmaker, beloved (and despised) the world over for his invaluable contributions to the pop-culture lexicon, had stuck to making space operas and juvenile fantasies about archeologists in fedora hats? What if George Lucas never entered the arena of gaming 30 years ago?

LucasArts revolutionized, created, or nurtured several whole genres, so its absence would’ve irreparably hindered the burgeoning video game medium. The San Francisco-based developer and publisher gave the point-and-click adventure – a heretofore obscure niche – a serious shot in the arm (and doctors everywhere an influx of carpal tunnel patients).

It reinvigorated the space shooter, redefined console RPGs, and when Jar Jar Binks took a dump on the collective geek fandom, it even reignited the ailing Star Wars franchise. LucasArts games have appeared on every major console, from early 1980s consoles such as the Atari 2600 and the Intellivision to the Xbox 360, PS3, Wii, including dank parlors of teenage truancy (i.e., arcades).

LucasArts has dabbled in almost every genre in gaming: point-and-click adventures, space shooters, first-person shooters, action, sidescrollers, role-playing games, MMORPGs, and even fighting games.

Suffice to say that the forerunner of Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Maniac Mansion, and Monkey Island had a significant impact on gaming.

Humble beginnings

Humble beginnings

George Lucas founded LucasArts, the gaming arm of LucasFilm, in 1982 – the same year that Lucas’ frequent collaborator, Steven Spielberg, unleashed the interactive version of his adorable, alcoholic, bipedal alien, E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial. While the latter nearly destroyed gaming in its infancy, LucasArts would weather the great crash of 1983 and reemerge for the medium’s second renaissance in North America in 1985.

LucasArts originally partnered with the premier North American video game company – Atari – and in 1984, produced inventive action titles like Ballblazer and Rescue on Fractalus! for the 5200 and 7800 systems. PC versions followed a year later.

During the era of Reagan, greed, and the imminent fall of the Soviet Union (aka the 1980s), LucasArts developed a number of military simulations, including PHM Pegasus (1986), Strike Fleet (1987), and Battlehawks 1942 (1989). This was no accident.

One of Lucas’ prime inspirations for the Star Wars trilogy – especially the gee-wiz, outerspace dogfighting scenes – were swashbuckling, jingoistic World War II flicks, and he’d explore this more directly with the 2012 film Red Tails.

LucasArts would revisit combat sims years later, but under the guise of its flagship franchise – Star Wars: Rogue Squadron (1998) and Star Wars: Starfighter (2001), to name but a few. They’d also return to the WWII era with 2003’s aerial-warfare title, Secret Weapons Over Normandy.

Planting the point-and-click adventure flag

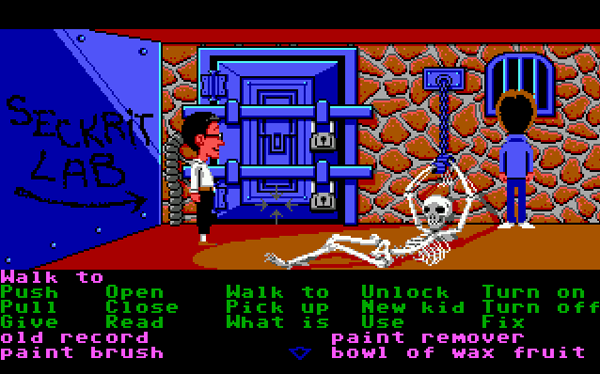

LucasArts found its stride with repetitive mouse clicks and a little game called Maniac Mansion (1987). Creators Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick designed a loving tribute to B-movies, kitschy horror films, and ’80s teen flicks.

Maniac Mansion – based on Skywalker Ranch – gave the intrepid point-and-click explorer the opportunity to solve puzzles, navigate the sort of prepubescent stupidity that only exists in horror flicks, and for the budding serial killer, microwave a hamster. Seriously.

It also introduced the Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion (SCUMM), a scripting/programming language that saw action in every subsequent LucasArts adventure game.

SCUMM was the subject of numerous in-jokes, not the least of which was the Razor and the Scummettes band from Maniac Mansion and the “SCUMM bar” in The Secret of Monkey Island (1990).

The latter, of course, established LucasArts as the premier developer of adventure games on the planet. Maniac Mansion and SCUMM alumni, Ron Gilbert, returned for The Secret of Monkey Island, and a young Tim Schafer (Grim Fandango, Psychonauts, Brütal Legend) cut his teeth on this seminal adventure title.

Apart from Star Wars, Monkey Island is probably LucasArts’ most enduring franchise.

Teenaged pirate Guybrush Threepwood returned for four sequels, including Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge (1991), The Curse of Monkey Island (1997), Escape from Monkey Island (2000), and the episodic Tales of Monkey Island (2009).

Talk about longevity – from the original Monkey Island to Tales, the series spans nearly two decades. This puts it roughly equivalent to video game stalwarts (and franchise superstars) like Mega Man, the latter of which only has about four years on Monkey Island.

Indy takes the spotlight

Before LucasArts made its bones in the adventure genre with Maniac Mansion, it dipped its toes in the water with Labyrinth, based on the Jim Henson (and Lucasfilm) fantasy movie. But that was just a taste.

The globetrotting archeologist (of the fedora hat and whip variety) also saw numerous video-game adaptations. Many of the early Indiana Jones titles were movie tie-ins (Raiders of the Lost Ark for the Atari 2600, The Last Crusade for the Genesis and NES), and LucasArts didn’t publish or develop most of them.

The house that Lucas built assumed auteur duties for the point-and-click adventure game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (1992), a critically acclaimed genre title, and LucasArts subsequently took charge for Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine (1999), Indiana Jones and the Emperor’s Tomb (2003), and Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings (2009).

Alas, I feel like I’m forgetting one particular franchise…

Wars among the stars

LucasFilm’s cash cow was a stalwart of video gaming since Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1982) for the Atari 2600 and Mattel Intellivision and the Star Wars arcade game (1983). But Lucas’ in-house development studio didn’t work on it until the X-Wing franchise.

LucasFilm’s cash cow was a stalwart of video gaming since Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1982) for the Atari 2600 and Mattel Intellivision and the Star Wars arcade game (1983). But Lucas’ in-house development studio didn’t work on it until the X-Wing franchise.

The DOS-based space-combat sim put you in the cockpit of various Rebel starfighters – X-wings, Y-wings, and A-wings – ultimately tasking you with assaulting the Death Star itself. Lead designer Lawrence Holland borrowed a number of gameplay elements from his previous WWII flight sim, Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe.

X-Wing included a revolutionary 3D flight engine, the template for every succeeding space-combat sim, and won the Origins Award for Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1993.

But it was the sequel – much like with the Star Wars cinematic franchise – that ensured X-Wing’s enduring legacy.

Remember Vader’s wingmen from A New Hope (DS-61-2 and DS-61-3, if my memory serves … yes, I’m a hopeless Star Wars geek)? Ever wanted to be them (or a reasonable facsimile, given that those two chuckleheads screwed up, one collided with Vader, and essentially helped saved the Alliance)?

Star Wars: TIE Fighter (1994) gave budding Imperialists the chance to play as the bad guys. This was followed by the multiplayer-oriented X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter (1997) and later by X-Wing Alliance (1999).

Star Wars: TIE Fighter (1994) gave budding Imperialists the chance to play as the bad guys. This was followed by the multiplayer-oriented X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter (1997) and later by X-Wing Alliance (1999).

Star Wars: Rebel Assault (1993) uses FMV cut-scenes, pre-rendered 3D backdrops, and digitized music and footage from the movies to re-create the trilogy beneath the helmet and behind the trigger of “Rookie One” (a transparent stand-in for another famous Tatooine moisture farmer who walks among the sky).

The sequel, Rebel Assault II: The Hidden Empire (1995), incorporated original footage of real actors, with high production values and expert use of John Williams’ iconic score. But the clunky, on-rails gameplay kept the game from achieving its predecessor’s fortune and glory (to reference another famous LucasArts franchise).

Meatbags, Jedi, and console RPGs

By 2002, the consensus among the collective Star Wars fandom was that the franchise was overexposed. Episode I: The Phantom Menace took the series in what some perceived as a new kid-friendly direction, alienating long-time fans, and most of the games that followed in its wake were mediocre (at best).

Then along came a console role-playing game called Knights of the old Republic (2003), featuring customizable classes, witty dialogue, and a mature, multilayered narrative. In other words, it was everything that the prequel trilogy (Episodes I, II, and III) tried (and mostly failed) to be. KOTOR was an immediate hit with gamers, and PC and Mac ports followed shortly thereafter.

LucasArts published the sequel, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II — The Sith Lords, for the Xbox and Windows PC in 2004 and 2005, respectively.

‘Block’ party

In 2005, LucasArts inaugurated the Lego video game craze with Lego Star Wars: The Video Game, an instant multiplayer classic. And since your characters could never truly die (they explode in a cacophony of cute, Lego body parts, only to instantly respawn), it’s also a family-friendly classic.

While not the first Lego-branded video game (that would be 1997’s Lego Island), it indisputably launched the current renaissance, and its success compelled LucasArts to release a slew of sequels and spinoffs, including Lego Star Wars II: The Original Trilogy (2006), Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga (2007), a compilation of the prior two, and Lego Star Wars III: The Clone Wars (2011).

Henry Jones Junior (aka Indiana) also got a couple titles, Lego Indiana Jones: The Original Adventures (2008) and Lego Indiana Jones 2: The Adventure Continues (2009).

Credit LucasArts for igniting the Lego gaming craze – non-Lucas franchises, including Batman and Harry Potter, rode the former’s wave of success.

Experimental phase

Star Wars: Dark Forces (1995) capitalized on the popularity of Doom and took the Star Wars franchise into the realm of first-person shooters. It spawned a sequel, Star Wars: Jedi Knight — Dark Forces II (1997) and the Star Wars: Jedi Knight third-person action series.

LucasArts dabbled in strategy with Star Wars: Rebellion (1998), Star Wars: Galactic Battlegrounds (2001) and Star Wars: Empire at War (2006), and it ventured into the tempestuous world of massively multiplayer online role-playing games with Star Wars: Galaxies (2003) and Star Wars: The Old Republic (2011). While the former was plagued by bugs and an overly complex progression and class system, the latter acquitted itself much better.

LucasArts dabbled in strategy with Star Wars: Rebellion (1998), Star Wars: Galactic Battlegrounds (2001) and Star Wars: Empire at War (2006), and it ventured into the tempestuous world of massively multiplayer online role-playing games with Star Wars: Galaxies (2003) and Star Wars: The Old Republic (2011). While the former was plagued by bugs and an overly complex progression and class system, the latter acquitted itself much better.

In one of the most bizarre uses of the Star Wars license, LucasArts created the 1997 fighting game, Masters of Teräs Käsi, a poorly received mess.

Third-person action title Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire, a multimedia craze (punctuated by the official canonical sanctioning by one George Lucas), launched with the Nintendo 64 in 1996, while the recent Star Wars: The Force Unleashed (2008) presented an uncommonly superb narrative, even if it was mechanically flawed (and even if the 2010 sequel threw out all the nuance and subtlety of its predecessor).

The future

By now, you’ve undoubtedly heard that everybody’s favorite cartoon mouse purchased Lucasfilm (and LucasArts) for a cool $4.05 billion. What does this mean for the future of the gaming division? Lucasfilm spokesperson Barbara Gamlen told GamesBeat that “For the time being, all projects are business as usual.”

This might suggest that Disney has no plans to tinker with the forthcoming Star Wars 1313, the M-rated action-adventure title revealed at this year’s E3 (to the delight of fanboys everywhere, myself included). But considering the mass-media juggernaut’s family-friendly facade, gamers are rightfully concerned.

GamesBeat will continue to document the rich history of LucasArts as it develops and hope that a new chairman of the board subscribes to the light side of the force.

Here’s to 30 more years of quality LucasArts gaming.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More