The Casual Games Association paid for Daniel Crawley’s trip to Casual Connect Europe, where he moderated two sessions. Our coverage remains objective.

Yosef Safi Harb is one of the most amiable game developers you’ll meet. He’s also an ex-aerospace engineer who’s created a mobile game that you control with your heart — the first of its kind.

Safi Harb is based in Amsterdam, where his small company, Happitech, is gaining notice with its first iOS release, Skip a Beat. I met up with three of the team at Casual Connect Europe on the day their game — two years in the making — released on the iOS App Store. It was a pretty big moment for them all, and their joy at seeing their passion project finally hit the market was kind of infectious.

When Julie Christine Wolsak, who joined Happitech as operations manager five months ago, told me her mother was heading to the Apple store to buy an iPhone just so she could play the game, it brought home how much the development process means to young companies — and how hard it can be at times.

Some darn clever tech

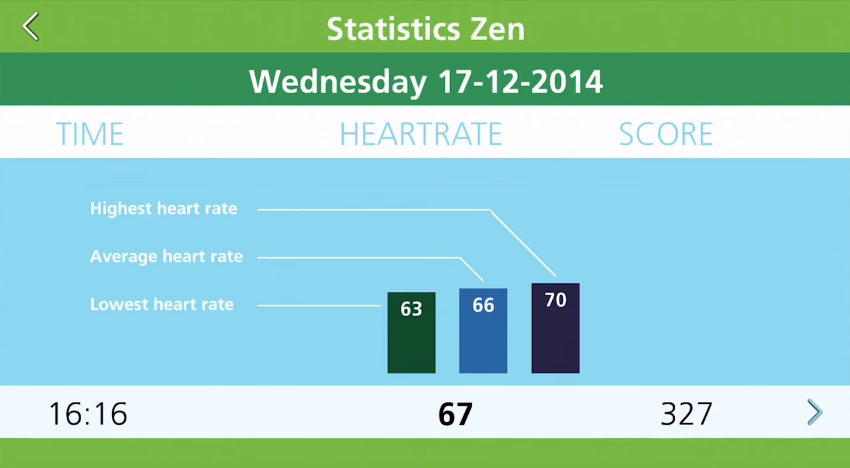

Safi Harb showed me how the technology behind Skip a Beat works. It uses the camera and flash on your iPhone to measure the blood flow moving through your finger. The tiny red pixel changes on the resulting video stream are nearly undetectable to the human eye (trust me, I tried to see them on the test screen that Safi Harb showed me), but they’re enough to measure your heartbeat accurately to within 3 to 5 beats per minute when done correctly.

It plays like a zen version of Flappy Bird, with you keeping your frog floating through a combination of staying calm and tapping the display. Seeing your own heartbeat displayed in the corner of the screen is strange at first, and the gradual realization that you can control it to a certain degree, with the way you sit, breath, and think, is pretty mind-blowing.

But Getting Skip a Beat to its launch state hasn’t been easy.

Sorry, you’re baby’s not that beautiful

Initial playtesting was with friends and family, which proved more or less useless, said Wolsak: “Friends are always, ‘Oh, it’s so nice,’ and we’re like, ‘OK, that doesn’t help.’” Even hitting the streets of Amsterdam wasn’t that helpful, as the people giving feedback still had to do it face-to-face and were far too “nice.”

Happitech turned to an anonymous testing service, PlaytestCloud, to get some better feedback. What they heard was tough to take.

“It was really hard for Yosef,” said Wolsak.

“We got bashed,” said Safi Harb. “You have no clue. They did the reviews, and they were saying it’s terrible.”

PlaytestCloud sends gameplay video that tracks player actions on the touchscreen, and this was a real eye-opener. “There was one person who was just staring at the screen. They didn’t even know what to do, right?”

The game was Safi Harb’s baby, and Wolsak likened hearing the feedback to that cruel moment when misty-eyed parents realize their baby isn’t actually the most beautiful child in the world. “Your baby is really nice, but it’s not the most beautiful baby ever,” she said.

But the team took the feedback on board and improved their game as a result, realizing along the way that they’d been targeting the wrong audience.

“We kept improving, improving, improving,” said Safi Harb, “and we realized, ‘Wait a second, we shouldn’t be in the game section; we should be in health.’ The people we want to reach are people who are interested in their health.”

One of the key changes they made was to the difficulty — specifically the ways you can die (or not). I looked at some early stats, and a whole lot of people were dying from hitting the bottom of the screen. Now you can ride along there without fear of failure, and it makes for a more stress-free experience — something that’s pretty key for a game promoting health awareness.

“What we’ve heard is that people who are interested in the heart, they’re not interested in getting more frustrated because they’re dying,” said Safi Harb. “So give them a simple game experience which is kind of challenging.”

“It’s about the heart,” added Wolsak. “It’s not about how hard it is! It’s one of the first games where you need to calm down instead of stressing yourself out.”

With less focus on providing a hardcore gaming experience and more on the heart-rate functionality, Happitech has created a game that is now turning heads for the right reasons.

“Now it’s a really, really beautiful baby,” said Wolsak. “We’re really proud.”

The game that never was

Happitech hasn’t just been testing its heart-rate technology in Skip a Beat. The team made another game that never launched.

A maze game for two players, it required teamwork and showed some interesting trends when you examined the heart-rate data.

“If one person loses, you both lose and start over again, so there’s a feeling of loss of control,” said Safi Harb. “It’s really funny to see what it does to stress levels. We’ve tracked that and we see that a junior manager and a senior manager … their peaks are way different.”

The junior manager played the entire time worrying about failing, according to Safi Harb, while the senior manager was cool as a cucumber.

It sounds like a great idea, and “people loved it,” but the team decided it wasn’t good enough to launch. Instead, they took it a stage further and added elements like fire and water to the game that you could control with your heart rate.

“You’re the ball in the maze and you can change between elements,” said Happitech cofounder Jelmer Raaijmakers with a great deal of enthusiasm. “You can change into a fire ball, a water ball, depending on your heart rate. If you’re cool in water you’ll be ice — if you’re stressed you’ll be steam.”

They only made one level in the end, as the concept became impossible to live up to given the small size of the team. “It’s so ambitious,” said Safi Harb. “You need to be Disney to make that stuff.”

Getting a feature

Back to Skip a Beat, and the day after launch it was featured in the iOS app store’s educational games section in 70 countries. It was a huge moment for a team of first-time game developers whose backgrounds are firmly rooted in engineering.

“For first-time developers, we don’t know what’s behind the doors,” said Safi Harb. They were even unsure of the best way to even get on the iOS store for a while. Luckily, veteran developer Peter Molyneux kindly pointed them to the best person to email at Apple, and before long, they had a viable point of contact.

“Apple actually replies to your emails,” said Safi Harb, explaining his shock at receiving his first positive response. Getting a follow-up phone call was even more staggering.

But despite Apple’s reputation for mystery, Julie points out that “in the end, it’s people behind it.” Which is kind of good to hear.

Even after connecting with Apple, though, there was a lot of work to do — particularly for a team of self-confessed perfectionists. “If you read the last VentureBeat article,” laughed Safi Harb “[it says] we’re going live in August … we’re going live in September … we’re going live in November … and now we’re actually going live!”

At launch, Skip a Beat was the top health and fitness app on the Netherlands iOS app store. In fact it was the top-selling app overall for three days. It’s also hit the No. 1 spot for health and fitness apps in India, and it’s made the top 10 in that category in China, Canada, and Germany.

That’s impressive for a game that got bashed so comprehensively in its first round of proper playtesting.

Safi Harb reckon that Chinese success is partly down to Skip a Beat’s eye-catching graphics and partly because Asia is keen in health and biofeedback technology. He points to the Japanese viral success of the Necomimi brainwave cat ears as an example.

“We expect Japan and China to be our biggest markets; that is why we localized the Appstore description and screenshots,” said Safi Harb.

The future of Happitech

Happitech decided to make a Skip a Beat a paid-for app. In a mobile market dominated by in-app purchases and advertising dollars, it’s a brave decision. But Safi Harb thinks the proposition makes financial sense to people interested in tracking their health.

“Normally if you’re using a biofeedback device you’re paying 100 euros ($110) or 80 euros ($90) at least. We’re offering that same functionality plus a game for [a fraction] of the cost,” he said.

And Happitech is hoping to use the anonymous data that Skip a Beat collects, giving it meaning and sharing useful trends with its players. “People compared to your age have heart rates between this and this,” suggests Safi Harb.

Beyond that, there’s the potential for giving more specific data, provided Happitech can do this safely without impacting anyone’s privacy. “The best part would be that we could also do some predictive analysis,” said Safi Harb. “We’re measuring three minutes of heart rate data — that contains a lot of information because heart rate variability is kind of like a key into yourself.

“There are lots of applications of how to interpret the data and we just have to find, in the coming months, what is the best application — where is the biggest need.”

Thinking beyond the game, Happitech is also looking to license its technology to other developers for use in their own games. And a couple of days ago, Safi Harb told me that two major wearables companies had got in touch, although he didn’t divulge any further details.

“The next step is we want to create mindfulness apps all with health in mind,” explained Safi Harb. “So let developers make those awesome games or already use existing games that are out there and add this educational mindfullness to it. And we will be focusing on making the heart rate technology smarter by making the heart rate data more meaningful.”

Who knows, one day we might get to calm down those Angry Birds by deep breathing.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More