Unrelenting terror

Each game handles death slightly differently, but for the most part, it’s swift and brutal. You lose all the things you worked so hard to collect (or someone else picks them up from your body), and you end up spawning back in a different location on the map. It’s pretty disheartening to lose hours of progress because of a small mistake, but the developers love finding new ways of making that happen.

It’s no surprise then that zombies are so prevalent in the genre: They look creepy and they can attack in groups. Using zombies as an enemy isn’t the most original idea in video games, but DayZ and others like it have put a fresh spin on our never-ending war with these rotting corpses.

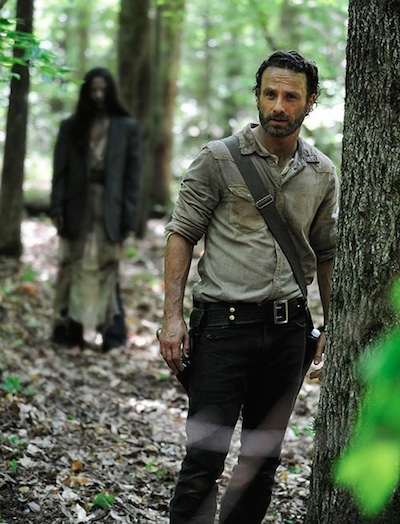

“My simple answer to [why the apocalypse is so popular in games right now] is The Walking Dead has taken zombies to a really mass-market level,” said John Smedley, president of Sony Online Entertainment, to GamesBeat. “It’s such a popular TV show that I think that thing has single-handedly given a massive boost to the zombie survival genre.”

AMC’s The Walking Dead, based on creator Robert Kirkman’s ongoing comic book series, just wrapped up its fourth season last month, where an average of 13.3 million viewers tuned in every Sunday night to watch the gory adventures of Rick Grimes and his constantly shrinking group of survivors.

SOE is hoping to capture some of that Walking Dead magic with H1Z1’s zombies, specifically with the concept of hordes, where dozens or even hundreds of zombies roam together in the post-apocalyptic wilderness.

“We want people to be afraid,” said Smedley. “Our goal is, by forcing that very scary threat on them, they are going to band together.”

Others have decided to just cut out the zombies entirely. When the alpha version of Rust launched in December, players had to worry about zombies while they scavenged for raw materials to craft weapons and shelters. But two months later, developer Facepunch Studios removed the undead and replaced them with tougher bears and wolves.

Nether eschewed zombies from the start in favor of agile monsters who use teleportation to get around. Unlike the vast countryside in DayZ or Rust, Phosphor Games’s vision of the apocalypse takes place in a more urban environment: a fallen metropolis partly inspired by the developers’ hometown of Chicago.

“Zombies in general tend to be an easier type of enemy to hold on a server because they don’t have ranged attacks,” said Chip Sineni, director and cofounder of Phosphor Games. “And the way they move is pretty slow. … We started designing around [problems] like zombies getting stuck a lot. We wanted to make sure our creatures never get stuck and that they’re always a threat and that they’re always gonna get you.”

Regardless of what they are, these enemies add some tension and horror to the otherwise monotonous task of collecting gear and ammo. Attracting the attention of just one zombie, monster, or animal can quickly pull in others, and before you know it, you’re running for your life. It’s that uneasiness, the thrill of not knowing when someone or something will attack you, that draws you into these games.

The power of emergent storytelling

Computer-controlled creatures can only do so much. The other half of the genre’s chaotic formula depends on the people behind the emotionless avatars you meet online. It all feels like some grand social experiment: Certain people will just shoot you on sight no matter how much you plead, but if you’re lucky, you’ll come across someone who’d happily feed you or heal your wounds. And the more bizarre stories — see the cult-like ritual from DayZ above — tend to go viral, strengthening the word-of-mouth marketing that these games rely on.

“The interesting thing is that when you’re looking at some of the research of online behavior — this is going back as far as the 1990s, with the emergence of the first chatrooms and later the first webpages … the anonymity of all of it is unleashing an id that’s inside of people, that maybe even they never realized is in there,” Donovan said. “If people are noticing this as early as the 1990s, now with these really advanced looking video games, it’s not a surprise that the technology is opening up sides to people that I would say are probably inside of all human beings.

“But it’s something that most of us don’t want to think about and acknowledge. But then you sit down and play a game like [DayZ] and suddenly it’s staring you in the face of what you’re capable of and what everyone else is capable of.”

That’s the flip-side of all this freedom: You’re not going to have a very good time if you’re mostly getting attacked by other players. During a recent play-through of Nether, for example, I had just finished killing one of the smaller monsters and was looking to see what kind of items it dropped when someone came from behind and shot me without any warning at all.

“I think the problem with these games is it’s too rewarding to just kill people to get more gear and more weapons,” said Sineni. “There aren’t a lot of reasons to befriend them. [With Nether,] we’re just trying to do that more and more, trying to group people up. … If you’re just a new player coming out of nowhere, and you want to jump on, you just have this world against you. We’re always trying to fix that without forcing players to play one way or another.”

When something fun or extraordinary happens to you, the apocalyptic setting becomes much more personal and unique, something that scripted stories, no matter their quality, simply can’t replicate. These spontaneous moments, also known as emergent storytelling, are a powerful part of the genre’s toolkit.