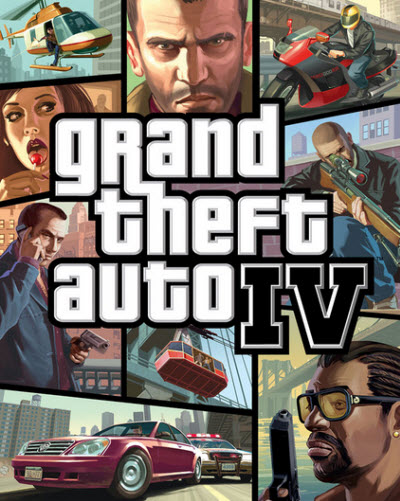

GamesBeat: What do you think the point was where these guys actually crossed over into making something that was of the highest quality? There’s a certain period of time where people thought they were making sensationalist games. They were not works of art. But if you look at GTA IV, it’s clear that they’ve crossed that point. When did you think that they got there?

Kushner: It’s funny, because if you talk to anyone who plays or is a fan of GTA, and I mean, look, I was certainly and remain a fan of the games. Everyone is going to tell you something different. People will say Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, people will say San Andreas, some will say GTA IV. I guess for me it’s Vice City because Vice City was funny. I would almost say it was the funniest of the games. I like the humor of it, I loved the social satire, that it was set in that period of time, that it was celebrating things like Miami Vice and Scarface. Just extrapolating that into this twisted gaming universe. And that it was just a pretty game. People don’t usually think of the word “pretty” when they think of GTA, but it really was a pretty game. All the sunsets of Vice City were terrific. So I think for me, Vice City was that moment. GTAIII certainly was a massive breakthrough, but Vice City defined the voice of that game in a way that it hadn’t before. The radio stations. Maybe more than anything, it gave you the freedom to explore a time and place that felt really palpable. I think that certainly that went on, that continued in San Andreas, and it did continue to GTA IV. Personally, I found GTA IV to be a little more dour than some of the earlier titles. But it’ll be interesting to see what GTA V holds.

GamesBeat: Yeah, you talk about how there isn’t much humor in GTA IV.

GamesBeat: Yeah, you talk about how there isn’t much humor in GTA IV.

Kushner: I’m not the first person to say that. But you know, it was cool, though. GTAIV, what I loved about it even more than the other games was just the detail, the attention to detail. That was incredible. Especially as someone who was living in New York, to basically go down to the equivalent of Brighton Beach in the game. That was cool because I knew Brighton Beach. It was amazing to see how detailed that was.

GamesBeat: It seems like an awful lot of years to cover here, maybe 15 years. Did you have a tough time deciding what to include and what to throw out?

Kushner: Um…. You know, that’s a good question. To me, writing is editing, ultimately. There’s so much information. So writing is editing. I used to have a great-uncle who had a linoleum business, and his motto was, “We always tell people to cut with confidence.” To cut the linoleum with confidence. To me, that’s what I had to do, and I guess what anybody has to do when you’re telling a story that unfolds over 15 years. The way that I approach it is to say, “What is the story? What is this about?” Then everything falls into place. It’s kind of about, and I wrote it in the first line of the book, which is “How far would you go for something you believe in?” That was the reason I did that because, to me, that was the theme of the story. On the one hand you had these gamers who completely believed in what they were doing, and how far would they go for what they believed in? And on the other side you had these “haters,” and how far would they go? Because they certainly believed what they felt. I tried to just stay out of the way and tell that story. Not be judgmental, not caricature anybody, and just kind of render as it was the best as I could.

GamesBeat: It is written as a narrative as well. I wondered if there was any part where you felt like you could take some license — almost fictional license, or whether everything that’s in there is written either as an eyewitness or something rooted in a document or something like that. I wondered: When you’re setting up some of these conversations between these people, you’re obviously not there…. How do you do that?

Kushner: That’s certainly something. I’m not the first person to have to contend with it. But it’s the same as I did for Masters of Doom or any story I’ve ever written. Journalists have had that same challenge for a long time. Every single thing in there is drawn from either a document or an interview, and nothing is fictionalized. Everything that’s in there came from the reporting. What I did, and what I like to do, is to make it cinematic. Just to give the reader a feeling that they’re there. All the dialogue and all of the e-mails and everything came directly from documents. The great thing is, with a story like this, you don’t have to make anything up. It’s all reality. That’s why I write non-fiction: because reality is way more compelling than anything you could imagine.

GamesBeat: One of the parts that I thought was actually a good idea was the writing about their experience as they played their own games.

Kushner: That’s a good example. Somewhere, I had read about Sam Houser talking about how much he loves to play darts in the game. I read about that and why he liked it, and why he liked it, as I recall, was because maybe he wasn’t as good of a darts player in real life or something like that. The way, I think, to write that, to keep a reader in the story, is to write that from the point of view of sitting down to play it. That’s in GTAIV, where you can go and play darts. I just think you’re trying to keep the reader in the story, and you’re trying to humanize it. To filter it through the eyes of the people who are experiencing that. It’s the same way that I might describe Jack Thompson playing GTA. What’s it like for Jack to play GTA, to look at GTA? That’s what I try to do. When possible, it was nice to be able to describe the game through the eyes of whoever was playing it. This is a big moment early in the book, and one of the moments I found kind of funny, which is when they had game testers come in to DMA Design in Scotland, sit down, and play. They had all of these people playing it who were running this. This is at the time when the game was set up so you were a cop. All these people were sitting down playing and they wanted to just run stoplights. And you had all of these programmers saying, “No, you can’t do that. You’re a cop. You can’t run the stoplights.” And people are just mowing through stuff, mowing over people, running through stoplights. That was important because their point of view was, “Why can’t I run the stoplights? This is a video game.” And of course that was a huge epiphany for the developers, and I got their point of view on it. That was when they said, “Just let ’em be the bad guy.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More