Ask any game artist what they’re packing in their toolbox, and I guarantee the vast majority will name drop an Autodesk application. Being a game artist myself, I can’t remember a time where I didn’t have 3D Studio Max and Maya installed on my work machine.

While you have that game artist’s attention, ask them what they think of Autodesk getting into the game-engine business. If it’s their first time hearing this, I suspect their face will twist into a what-the-fuck shape as everything processes in their brain.

Yet, that whimsical “what if” is becoming a reality. The owners of Maya, 3ds Max, and Mudbox have gone and overhauled the Bitsquid engine, which Autodesk purchased in June 2014, and heavily modified it into Stingray.

In a private demo, I got to look at Stingray. It has some serious potential to, if anything, alter the development pipeline.

The pipeline today

The big-picture idea that Autodesk is shooting for with Stingray is cross-program integration. The current pipeline for an artist is crammed with several different programs, all acting as self-contained environments locking down an art asset at different stages:

All-purpose 3D programs, such as Autodesk’s Maya and 3ds Max, are primarily used for basic polygon modeling, skeletal rigging, and animation. Then, 2D raster programs like Adobe’s Photoshop are used to tweak and paint texture maps. High-resolution sculpting programs like Pixologic’s ZBrush and Autodesk’s Mudbox are used to create pre-render level models and to generate special in-game textures (such as normal maps).

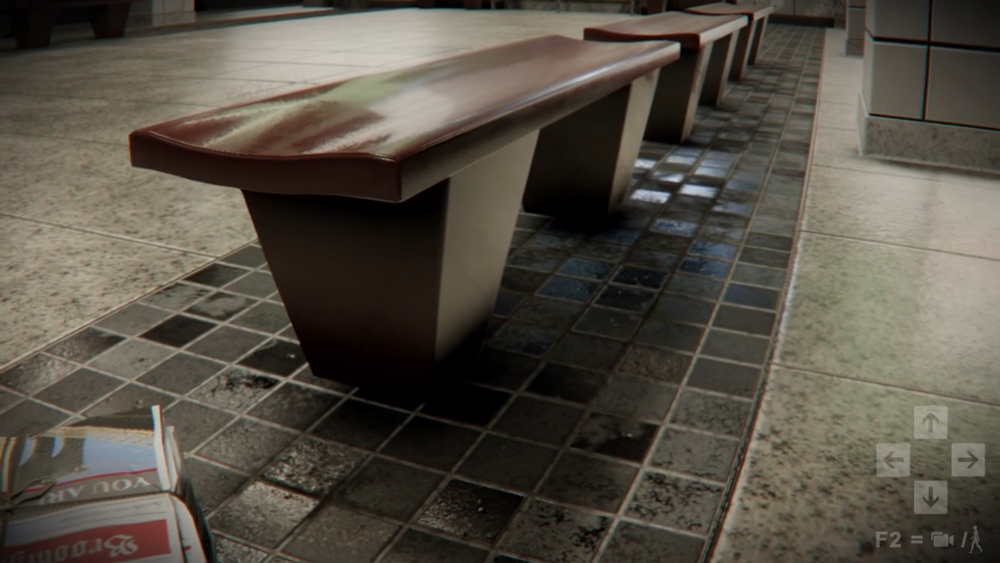

An in-game object as simple as a crate, in a current generation game, can have a lot of different elements to it, which require multiple programs to generate. Usually, when the asset reaches the game engine, it still isn’t complete. So the artist spends a lot of time refining the object, bouncing back and forth between the game engine and these other programs to tweak it.

This hopping back and forth doesn’t sound horrible to the uninitiated, especially when talking about making a change or two to an object. The thing is, it is never just a change or two. Oftentimes, hundreds of changes are necessary. And those moments are filled with monotonous reloading and checking of work that add up in both hours and tedium.

Making the pipeline smoother

So, we have a procedure that requires a lot of jumping from program to program, reloading files, and reinitiating a game engine to check the work. Autodesk happens to develop a good chunk of the programs involved in this pipeline, which gives the company an advantage when it comes to improving this process.

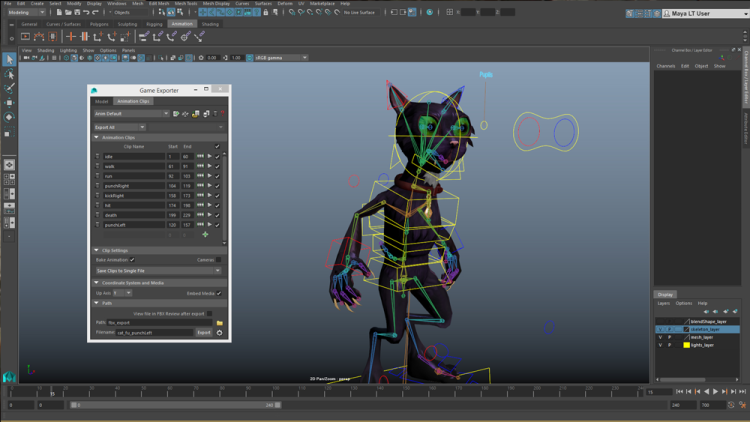

Stringray’s first big feature is how its editor can work in conjunction with Maya. Portions of the demo I saw showed how the artist could manipulate a character’s 3D model in Maya and have the changes show up in Stingray in just a few seconds. A bit of a pause still exists in the process to allow the asset to load, but no convoluted file manipulation is required. Make a change, click a button, and the change shows up in Stingray.

Another hassle of the traditional pipeline is the difference between what you see in one program and what you get in a game. This problem is partially tied to shaders. Put as simply as possible, think of shaders as a collection of information that tells the game engine how to make the surface of an object look.

For example, some shaders make an otherwise flat polygon surface look like a pool of water. Another shader applied to the same polygon can make it look like a solid brick wall. Manipulating shaders is one of the 3D game artist’s most valued skills, because they can turn basic shapes into detailed objects.

Part of the problem used to be that you could create a cool real-time friendly shader in Maya, but that shader didn’t necessarily translate to Unity or Unreal. If the shader system in one program is different from the game engine’s, replicating the shader meant a lot of translation work between the two programs. Which didn’t necessarily guarantee that the shader would function exactly the same.

So, again, the artist that has to go back and tweak an object outside of the game engine was not necessarily seeing what he was going to get in the game.

To fix this issue, Autodesk implemented the shader editor, ShaderFX, into both Stingray and Maya. ShaderFX is a node-based editor that allows artists to manipulate shaders visually. Users manipulate a visual graph that is filled with individual pieces of data (nodes in this situation), as opposed to having to hardcode the shader via a coding or scripting language.

The fact that both Maya and Stingray use the same shader network means that artists can confidently see an object they are working on and know how it will look in a game. As a side bonus, even if the artist creates a shader that’s wildly inefficient for the game engine or does not meet the programmers’ specifications, a coder could tweak the shader and give it back to the artist. The shader can then be plugged into Maya without any hassle.

Another major annoyance for everyone involved in game development is checking work on multiple platforms. Typically, if someone wants to make sure something is working correctly on a multiplatform project, the person stuck having to check the change has to load the tweak in the game editor and render out a test build of the game to run on said platform. This can mean rendering several different types of test builds for different platforms just to check if one tweak looks OK.

Autodesk has implemented a quick cross-platform deployment system that allows developers to set up an instance of the Stingray editor that sort of streams to another device, such as a mobile phone or a game console. Not only can all edits be seen on the gaming device, but the game can also be built and run from there as well. This feature can wind up being a big time saver.

Visual coding

One of the truisms of those who enter game development is that they tend to start off as one of two types of people: a good artist that’s terrible at coding or a good coder that’s lousy at art.

To help those that are programming illiterate, Autodesk is introducing a node-based coding system in Stingray. I know some hardcore coders are going to look down on this feature, preferring to write out every little nuance of a game in their language of choice (which Autodesk assures you can still do if that’s your thing).

The thing is, visual node-based scripting is a smart feature to implement at this time. Game development has been progressing toward becoming more accessible, but the abstract nature of programming is still a tough obstacle to climb for many.

It’s beneficial when we can allow people to put together simple gameplay prototypes and behavioral scripts, that they would otherwise fail to create when handed a text editor and a giant manual. This node based editor could even, perhaps, be a great educational tool as well — a tactile Lego set of code that give those who learn visually a new perspective on how scripting works. I’m excited to see how this node-editor works and what can be done with it.

Sounds great! Can I test drive the floor model yet?

I’ve been fooling around with different engines as an artist for many years. On the surface, Stingray seems to offer someone like myself a lot of great benefits. I love the visual coding aspect, and the steps being made toward eliminating the tedium of the pipeline are fantastic. You will need to pay the licensing fee, by the way, which runs $30 a month. That includes a subscription to Maya LT as a bonus.

All this stuff is great, but we’re still just dealing with hype from the sales brochure.

Although Autodesk showed a live demonstration of Stingray’s features at GDC 2015, I have to keep my enthusiasm in check. I need to feel the tool in my hands. I need to be allowed to swing it around a few times and maybe see what others are creating with it before fully investing my enthusiasm. If Autodesk can nail all of this stuff in the first revision, however, Unity and Unreal have a serious problem.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More