Above: Bruce Nesmith speaking at Game Design Expo 2012 (image credit: Vancouver Film School)

When the development team of Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls role-playing game series began to work on Skyrim, the need to make the game world understand itself in relationship to the player was identified. But that was easier said than done, as Bethesda’s director of design Bruce Nesmith recalled from a conversation he had with executive producer Todd Howard:

Todd: “I like that responsive thing. Give me some examples.”

Bruce: “So when I kill a guy, his family will come after me.”

Todd: “Give me some examples that aren’t about killing someone.”

Bruce: “…uh…”

Nesmith gave a lecture on the development of Skyrim’s new “Radiant Story” system during the 2012 Game Design Expo hosted by the Vancouver Film School. His team’s goal was for the player to “feel like he’s part of the world and not just moving through a still life painting”. Skyrim’s genesis is interesting because it was one of the best-selling games of the holiday season and it took more than five years to develop.

In order to achieve that the developers started by defining 30 player actions and ways the rest of the game world might react to them. These included small things like having bystanders gawk at a slain dragon, tussle over an item that was dropped to the ground, asking the player for a potion after witnessing her alchemy skills, or even just having an item topple over when the player brushes past them.

Nesmith pointed out that “just because a response was reasonable in the real world, it doesn’t mean it’s good in a game”. For example, originally an NPC [non-player character] could claim that an item bought from a vendor was stolen and demand it back, but it was scrapped for story reasons because “it didn’t feel good; you ended up always killing the guy”.

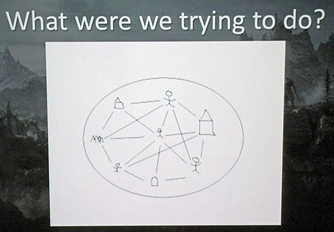

Above: The player is the centre of the game world

Skyrim’s “Radiant Story” system tailors quests to the player, their progress and relationships in the game world. As a result, a never-ending stream of generated quests can be placed specifically in locations the player hasn’t visited yet and be related to earlier adventures. Nesmith called it a “pretty Herculean task” to create the necessary new data types and add these to objects in the game.

But during development the Bethesda team realized that it was “really easy going too far with that kind of thing.” For example, they discussed the idea of using the Radiant Story system for the main quest. “Sounds great, would play horribly”, quipped Nesmith, because a hand-crafted storyline is always more intriguing than quest objectives cranked out by an automated system.

Still he encouraged the audience of aspiring game designers to push the boundaries, as long as they realize when it’s time to dial back: “If you don’t end up going too far, you’re not stretching yourself as a game developer. It’s like in football: if the team isn’t taking any penalties, it’s probably not playing hard enough.”

Several course corrections were required during development of Skyrim’s Radiant Story system. Job quests were limited to certain NPCs that felt right for them, like innkeepers, to avoid Radiant quests feeling mechanical. To reduce repetition, custom dialog lines were written for different NPC voice types. Conditioning limits had to be expanded so that certain events wouldn’t happen too often: “When every time I drop something on the ground, half the town comes over, it is starting to get really silly”, Nesmith recalled.

The Skyrim team also realized that players only want so many of the “job quests” that are not advancing the main story. “We ended up doing many more custom pieces. It felt better.”, concluded Nesmith, “Players expect from game developers that we use our creativity to create content they want to experience. If we pass the buck to a system, it’s not the same.” He doesn’t expect that a procedural story system will be able to deliver results of a similar quality level to hand-crafted content anytime soon.

The inner workings of the Radiant Story system are exposed in the Skyrim Creation Kit Bethesda is about to release for the PC version, enabling players to come up with their own modifications, which can then be loaded into the game.

The Vancouver Game Design Expo is an annual event organized by the Vancouver Film School (VSF) to raise the profile of its game design program. Bethesda’s Bruce Nesmith was one of the lecturers during the VentureBeat-attended Industry Speaker’s Day that took place at the VanCity Theatre on January 21, 2012.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More