Why does DeWitt become Comstock?

When I asked the GamesBeat staff for their questions about Infinite, this one came back again and again. Why would DeWitt, who turns to Christianity to try to escape the atrocities he committed at Wounded Knee, become Comstock, who plans even greater atrocities?

The Natural Asshole Theory

Since my coworkers had nothing, I attempted to outsource a solution, preferably from someone smarter than I am. I wanted to talk to someone familiar with the technical aspects of drama and character, so I reached out to Cassandra Silver, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies to see what she could come up with.

She came up with a lot, but here’s a sample.

[C]onsider a few things about Booker in the universe in which he refuses baptism. Think about the exchange that Booker has with Elizabeth shortly after she kills Daisy. Elizabeth asks Booker how he gets over killing people. He tells her that he doesn’t, that he just learns to live with the knowledge of what he’s done. He seems to suggest that she shouldn’t bother with regret or remorse, that she should just put her action behind her and move forward. He suggests that he knows himself as a man who is capable of murder and indeed as a person who has killed. He self-identifies as a killer.

Relatedly, consider the ease of Booker’s violence. Of course, options are necessarily delimited by the game construction, but from the get-go he is violently aggressive. At the fair, when he “wins” the raffle, his two choices are to throw the ball at the couple or at the hawker. There is no third button to walk away. (I recognize that this isn’t a sandbox and that the game needs an active choice to push the story forward, but the fact that his only options are aggressive is indicative of something significant about his character.)

[Edit: A commenter points out, correctly, that one can choose not to throw the ball at either party by letting the decision timer expire. Immediately afterward, however, the game removes player control so Booker can graphically shove one guard’s face into another’s Skyhook regardless of the previous decision, so the game is still painting him as violently aggressive in this scene.]

Jump to the end of the narrative, and we see Booker, seething with anger, brutally beat and then drown Comstock. Violence is his primary action from beginning to end. Based on this, I would suggest that Booker’s fundamental nature is aggressive and even violent, and that this is consequently true of Comstock as well.

And so, in Columbia, he cobbles together the bits of ideology that allow him to justify his megalomania and wrest complete control from those who find comfort in absolute leadership. In this interpretation, he never regretted his actions at Wounded Knee; he just didn’t have a good reason for them. He didn’t have the right story to fit his experience. We see his continued tendency toward violence inside of Columbia made manifest in the spectacle of the public beating

of the mixed-race couple and in the exhibits in the Hall of Heroes.Comstock has recuperated his violence to control his population. It isn’t a surprise, then, that in an alternate future Comstock would want to send his flying city to destroy New York. He never had a problem with violence or with totalitarianism, and the story that he weaves to help explain his actions allows for one group of people to dominate another in the service of a “greater good.”

So basically, Booker is a violent jackass no matter what he calls himself.

The Monopoly Theory

Shamus Young wrote an interesting column at The Escapist in which he offers the following possibility:

[Comstock] seems to have a twisted view of both baptism and his religion. Instead of repenting of his evil, he acts like baptism is some kind of “get out of guilt for free card.” Instead of feeling remorse at his crimes, he celebrates them and uses them to build his persona as a heroic figure. [. . .] At some point Comstock gets the idea to baptize the world in fire. Baptism worked so well for him, so he figures it will be good for the human race in a “doomsday that kills all unbelievers” kind of way.

Young supposes that rather than helping him justify his crimes, Comstock’s baptism frees his mind to focus on his next big project: himself. His new identity garners him a congregation — later worshippers — who bloat his sense of self-worth. And if you dangle a floating warship-city in front of a guy like that, he’s guaranteed to do increasingly self-aggrandizing things with it.

“Another Ark for Another Time”

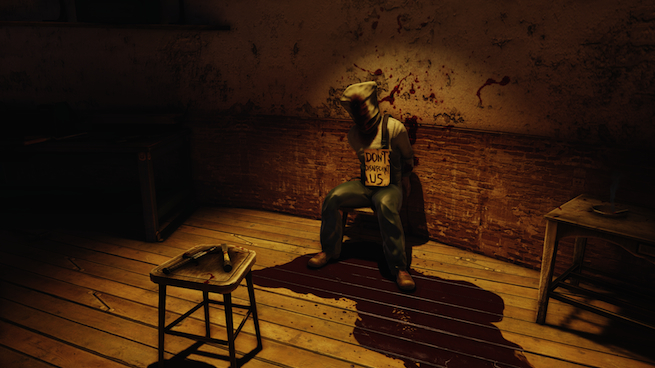

Who was that guy in the chair?

When DeWitt first arrives at the lighthouse that serves as the entry point to Columbia, he finds a tortured and bloody corpse with an ominous note (“Don’t disappoint us”) pinned to it. We might assume at this point that the body serves as a warning to DeWitt from his shadowy employers: succeed, or this will happen to you.

But once you’ve finished the game, that corpse makes no sense. DeWitt has no “shadowy employers”; he’s going to Columbia to wrap up the Luteces’ unfinished business.

So who the hell is that guy?

A previous Booker

One forum poster has an interesting theory about the corpse’s identity: he is one of the 122 previous Bookers that the Luteces sent to save Elizabeth. He failed to do so, and the quantum twins left his body in the lighthouse as a warning to his successors.

I’m including this more as a fun guess than a particularly convincing one. For starters, the corpse wears the clothes of the Fink workers you fight later in the game and not what I assume would be the threadbare once-suit of a drunken, washed-up private detective. Nor does his hand bear the “A.D.” mark that Booker’s does. It’s also unclear whether the Luteces are actually using different Bookers from different universes or the same one, over and over. The latter seems far more likely; it makes the most sense that they give the same DeWitt who sold his child the chance to reclaim her. And Rosalind Lutece says as much on one of the Voxaphones:

“An Ultimatum”

So it’s probably not another Booker, but I do like the possibility.

A false memory

Before the game begins, we see a quotation from a book called “Barriers to Trans-Dimensional Travel” by R. Lutece (either Robert or Rosalind): “The mind of the subject will desperately struggle to create memories where none exist. …”

This idea is key to the plot, contributing to Booker’s amnesia and allowing the three or four giant revelations at the end of the game come as giant surprises to him when they otherwise wouldn’t. A poster in the same thread (linked to in the previous section) suspects that the man in the chair isn’t there at all but is instead a projection of DeWitt’s newly established identity as a gun-for-hire working for mysterious and sinister forces. One thing about mysterious and sinister forces: they love torturing and murdering people. And if they can leave a spooky note on them for the next person who walks by, that’s like Christmas plus their birthday.

According to the theory, Booker knows this, so he imagines this scary corpse into being. It doesn’t otherwise exist.

The lighthouse keeper

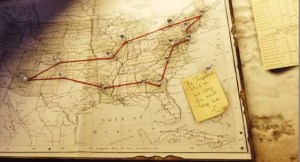

The most realistic possibility, however, is that the corpse is simply that of the man charged with guarding the lighthouse against Booker’s incursion. A note on the map in the previous room (at right) says, “Be prepared. He’s on his way. You must stop him. -C.”

The most realistic possibility, however, is that the corpse is simply that of the man charged with guarding the lighthouse against Booker’s incursion. A note on the map in the previous room (at right) says, “Be prepared. He’s on his way. You must stop him. -C.”

That note comes from Comstock and instructs the guard to stop Booker from reaching Columbia. The next logical question then is, how did he end up so tortured and dead?

Later in the game, you go to the Lutece home and discover a picture of the lighthouse with the note “only one obstacle.” That “one obstacle” has two parts: the code necessary to summon and enter Columbia and the guard who protects that code. It’s a little hard to imagine the prissy Luteces torturing and murdering a man, but it may have come down to a matter of utility. Whether they did it themselves or hired someone to do it, the “us” refers to them, and the sign — and even the body itself — are there to motivate Booker and impress upon his swiss-cheese brain that he is about to enter a very dangerous place.

And if you needed any more confirmation, skip to the 5:45 mark in this video from IGN. Irrational’s creative director Ken Levine identifies the body as the lighthouse keeper. He also mentions that the team added him very late in the game’s development, so everything in this section may still be suspect. But the important part is that that’s definitely the lighthouse keeper.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More