First, realize that Booker DeWitt isn’t a good guy. He’s a brutal, immoral thug who scalped women during the shameful massacre at Wounded Knee and handed his own daughter off to his creditors. Booker has never, ever made a good decision in his life, and those mistakes haunt him. He’s come to Columbia to kidnap Elizabeth, a teenage girl. It’s just happenstance that his task turns into a rescue mission. Booker’s only interested in wiping away his debt.

He just doesn’t understand that it’s really a karmic debt, not a monetary one. BioShock Infinite is about his redemption. That’s why Booker — not heroine Elizabeth or her monstrous guardian, Songbird — is on the cover. It’s his story.

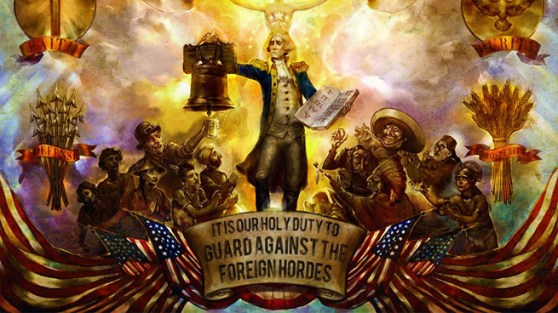

Through the magic of alternate realities, we even see just how much debt he’s racked up. The Booker DeWitt who justified his atrocities in the name of American greatness becomes Zachary Comstock, the architect of Columbia and its ultranationalistic “more American than America” creed. Yet another version of Booker commits mass murder for Vox Populi, the downtrodden rebels who readily become merciless oppressors the moment they overthrow Columbia’s ruling class. “Our” Booker merely slaughters his way through the city for his own selfish ends.

In every case, violence and fear are Booker’s only languages. When Comstock threatens to reveal sins that “our” Booker doesn’t remember committing, Booker instinctively murders him in cold blood to shut him up.

That prompts a question … the same question some people now ask about the extreme nature of every other killing in the game: Was that really necessary?

Possibly not. And that’s the point.

BioShock Infinite states, loud and clear, that there can be no morality in an extreme. Any extreme. Booker only finds his redemption when he finally lets go and chooses a middle ground. But to give his denouncement any kind of power, the road to it must be difficult. I’d argue that a few more orchestrated events to punctuate Booker’s violent tendencies might’ve had greater impact than hours of nonstop, frantic combat, but that would’ve made us, the players, less culpable. We participate in Booker’s rampages. We break those necks. We destroy those people.

Nothing in Infinite surpasses the kind of eviscerations and dismemberments you find in, say, God of War, Ninja Gaiden, or Metal Gear Rising: Revengence, but those games play at a safe, third-person remove. We, as Booker, take a step past what’s right and good and go into an uncomfortable extreme. That makes us more than ready for some catharsis when we come out on the other side.

I’ve seen people argue that this level of violence acts as a barrier to the message. You can’t show Infinite to your kids, your girlfriends, your parents. You can’t hold it up to the mainstream media as an example of the depth and thought-provoking maturity of modern video games. Not in our current hypersensitive, post-Sandy Hook atmosphere.

I understand wanting Infinite to transcend those limitations, and I don’t entirely buy the argument that it can’t. We have plenty of cultural touchstones that don’t shy away from bloodshed. Just looking at Best Picture winners, you’ve got The Godfather, Platoon, Braveheart, Gladiator, The Silence of the Lambs, and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, which sports a bodycount in the low 800s. Gory death punctuates those films without defining them. Violence has existed as a storytelling device stretching back to the ancient Greeks and beyond, and when it’s used to a real purpose, few things nail home a message with such authority.

Put BioShock Infinite in that category. Its violence makes you feel violence is wrong, and the story doesn’t just reinforce that idea … you’re forced to confront it. That’s something only a video game can do.

If only more video games did.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More