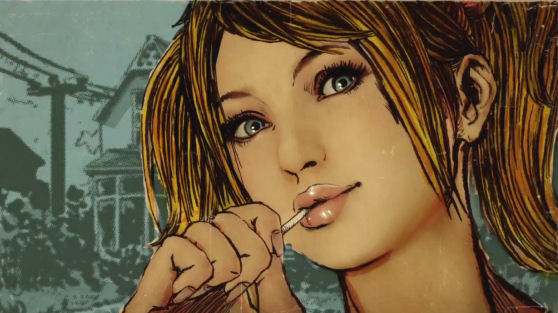

When the world first learned about Grasshopper Manufacture’s peppy action game Lollipop Chainsaw last year, more than one person connected the dots back to Buffy Summers, the Chosen One and all-around blonde bombshell who could deliver a roundhouse kick straight to your heart. Both are platinum beauties. Both enjoy decapitation and high school cheerleading. Both slay the undead. For Juliet, it’s zombies. For Buffy, it’s vampires and anything without a soul.

But Buffy came first, debuting on film in 1992 and later television, and she set an example far different than the one Juliet Starling embodies in Lollipop Chainsaw. Through show creator Joss Whedon’s feminist sensibilities, Buffy becomes more than a dream girlfriend — she plays sister to one, friend to many, and a role model to countless others. Sure, she chewed on a lollipop and wore miniskirts like Juliet (think back to Season One), but appearances do not make two characters evenly matched. Buffy deals with real death — the kind that wounds so deeply you don’t carry your boyfriend’s head around with you and use him to smack foes. She sacrifices herself for the good of the world and always comes back fighting.

For Juliet Starling to be a force as noble and unstoppable as Buffy Summers, she has to do a lot more than look hot in a tight outfit. She has to make us care about the difference between good and evil and show us that saving the world takes more than a chainsaw and someone bold or stupid enough to wield it. It takes a hero — and, in this case, a girl to inspire us, impassion us, and make us forget about gender and blonde jokes.

So, does Juliet amount to more than pom poms and glitter, or is she just another pretty face?

“Juliet is sweet and strong,” says Tara Strong, the voice of Juliet in Lollipop Chainsaw. “She has a real teenage quality in her, being hard on herself for having a ‘big butt’ and things like that. But then she can chainsaw someone in half…She’s the ultimate brave heroine, with a ton of fun girlie attributes. She always looks good, even when she gets splattered with blood.”

The problem is it seems nearly impossible to talk about Juliet’s redeeming personality and charm without mentioning her looks. Even the game’s developers focused less on Juliet’s brains than they did the zombies’, instead giving her a closet full of costumes and signing two cosplayers, one American and one Japanese, to play her in promotions.

Then the “Special Edition” live-action trailer hit the web in May.

In the video, marketing executive Ken Portman invites three of the game’s most “loyal and enthusiastic fans” to preview the special edition of Lollipop Chainsaw. He offers the teenage boys a chance to actually get their hands on a life-sized Juliet (cosplayer Jessica Nigri) and make her do whatever they dream up.

The most “enthusiastic” of the three starts counting the ways he’s going to play with Juliet after taking her home. His blatant sexual perversion, hardly decipherable through a storm of expletives, even makes his friends uncomfortable — not to mention Juliet herself. But she’s only a doll and does what they tell her to with a reassuring smile. It’s no small wonder the commercial (and its mildly less suggestive “Zom-Be-Gone” video counterpart) caused a stir in gaming communities.

Buffy fans may recall a handful of episodes involving a sex doll version of Ms. Summers (Season 5, Episode 18, “Intervention”) that one character had commissioned because he couldn’t satisfy his desire and love for the real version.

“Do I think that as a plotline it was somehow antiwoman?” says Lily Rothman, whose essay about the television show appears in the recent Joss Whedon: The Complete Companion from Titan Books. “Not really. There was never any implication, that I remember, that the bot could hold a candle to the real Buffy. If anything, it just shows how much more there is to the character beyond fighting and sex.”

After seeing the Lollipop Chainsaw live-action trailer, Rothman compares and contrasts Juliet and Buffy, looking beyond what she calls “superficial similarities” and pointing out the differences.

“Buffy isn’t fighting for a man, even though there are instances in which she does,” Rothman says. “She fights because it’s her destiny. She also doesn’t do it alone. And while she sometimes wore revealing outfits, mostly way-’90s thigh-high boots and miniskirts, she didn’t dress or act in that sort of way. This video game seems designed very much for the male gaze.”

Is there more to Juliet than “fighting and sex?” Did developer Grasshopper Manufacture mold a girl out of plastic parts, or did they create her with real flesh, blood, and bone?

Lollipop Chainsaw story writer and Hollywood filmmaker (Slither, Super) James Gunn believes the latter. Similar to Buffy’s destiny as the Slayer, Juliet has “been trained to kill since she was a baby,” he says. “I think we’d all have a different perspective on the world if that was our situation.”

Back in January, Gunn told IGN that Juliet has “an innocence about her that’s completely unique.” In relation to Juliet, who dresses in skimpy outfits and appears in life-size doll commercials, what does that mean?

“Well, I think Juliet is wide-eyed and innocent, but it isn’t in the typical way people try to portray innocence in characters,” Gunn says. “Usually, they mean ‘lack of sexual experience’ when they mean innocence. Although I don’t think Juliet has a lot of sexual experience, she has some, so she’s not innocent in that way. But I do think that she has this innocent, optimistic way of looking at the world — turning bad situations into something positive, and turning cataclysmically awful situations into slight bothers. She sees the good in almost anything and means no harm towards anyone. But cutting off the heads of zombies is second nature to her, and she loves it. It’s an unusual mix.”

Can, as Gunn phrases it, “blood and rainbows and little pink hearts” describe a girl whose one true love is massacring the undead, and can those ostensibly superficial qualities be genuine, as Gunn is suggesting? Buffy fought evil in “stylish yet affordable boots” (Season 6’s “Once More, with Feeling”) and would complain when she broke a nail or found a split end, but she’s still one of the most praised female characters in fiction.

Even Juliet’s relationship with Nick sounds comparable to Buffy’s romantic experience with former boyfriend Riley Finn, giving her a sense of depth. “He’s used to feeling like the one with the control in a relationship — and in one day he loses his body while simultaneously learning his girlfriend is capable of superhuman feats,” Gunn says. “This brings on a lot of feelings of worthlessness. The fact that Juliet sees the silver lining in everything becomes pretty irritating to Nick almost immediately.”

Many recognize Whedon’s character as a leading figure of feminist empowerment, but when it comes to Lollipop Chainsaw, people have commented on the derogatory and arguably misogynistic nature of the game. These allegations are steep, but they don’t worry Gunn.

“I think a lot of people have a difficult time distinguishing between lust and misogyny,” he says. “It would be dishonest to say that Lollipop Chainsaw doesn’t exploit — and I’m not using this term in a negative way — Juliet’s physical beauty. But I don’t think this is antiwoman any more than how Spartacus featuring male bodies is antimen. And I’m not even really on board with saying it’s not misogynistic because Juliet is a ‘strong character’ or ‘a symbol of female empowerment.’ I generally think that’s a simplistic way of looking at things.

“When a female character becomes only a symbol of female empowerment, you are nullifying who she is as a person, and that’s as misogynistic, or misanthropic, as the thing it’s supposedly reacting to. When I write — whether it’s a game or a movie — I feel the female characters as strongly as I do the male characters. I feel 100 percent female while writing them. I also feel 100 hundred percent female when listening to an Adele song, but that’s a different story. I think my female characters — whether it’s Starla in Slither, Ana in Dawn of the Dead, Libby in Super, or Juliet in Lollipop Chainsaw — are all fully rounded characters. I don’t fall back on the traditional, easy ideas of women solely as victims or solely as symbols of female empowerment. They’re weak in some ways, strong in some ways, smart in some ways, and stupid in others — but they’re full people, even in the case of Lollipop, which is largely a silly, spoofy, campy, rock ’n’ roll, in-your-face romp.

“What is misogynistic — or, at least, sexist — to me,” Gunn says, “are 90 percent of films and games out there that have a bunch of well-written male characters with exciting characteristics, and then a female character whose only personality trait would be ‘being pretty’ or ‘good.’ Think of 95 percent of every mainstream comedy ever. Boring! I wrote Juliet. I really truly love her as a character in the same exact way I love Nick and Gideon and the male characters in the game. So I don’t know where this supposed misogyny is rooted.”

Perhaps the explicit marketing surrounding Juliet Starling has diminished the power and potential of her character, making a bad impression. Maybe she’s just as admirable as Buffy is, only “far more flawed, sexual, and just overtly more comedic,” as Gunn thinks.

If Juliet is as eager to defend the world from zombies and find the good in the people around her as Buffy is, who are we to tell her to wear a longer skirt?

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More