Check out our Reviews Vault for past game reviews.

Correction 9:52 p.m. Sunday : The Philips Hue bulbs are $60, not $20 as this review initially said.

As an indie developer in 2015, it’s difficult to get noticed. Waving down attention from the masses gets significantly harder when your project is a 2D platformer, because, come on, it’s the genre every developer that grew up on the 8- and 16-bit eras has been dying to design.

So what do you do to get more eyeballs on your game? I say go the honorable, yet possibly naive, route: create a forward-thinking idea and have a good sense of play design. Others would recommend finding a gimmick and exploiting the hell out of that.

Firma Studio’s Chariot for the Xbox One (available now) decided to run with both suggestions.

Chariot looks like a clever and thoughtful side-scrolling platformer on its own, yet it has also adopted the gimmick of interacting with the Philips Hue line of lightbulbs. Playing with the colors in my game room sounds like a cool idea, but it is also the kind of feature that I’ve come to expect from projects trying to distract me from its flaws.

What is Firma Studios hiding behind this feature?

Before we play, I need to jerk around with some lights

I wasn’t familiar with Philips’ line of Hue lightbulbs, at least not enough to have installed them in my place. The starter packs seem to run between $80-$200, with replacement bulbs in the $20 range (product descriptions claim a life span of 24,000 hours), which is more than I am typically willing to spend on something as practical as light bulbs.

My copy of Chariot came with a starter set, which included three bulbs and a bridge. After playing around with the set for a while, I began to think $20 per bulb wasn’t a bad idea, and I was soon trying to calculate how much I’d need to run these bulbs throughout the house (the answer is, a small fortune).

Each bulb uses a wireless link to a central hub, which is connected to my home’s wired lan network via a RJ45 cable. After downloading the Philips Hue app on my mobile phone (Android and IOS supported), I was able to talk to each light bulb and change its color and brightness. When the bulbs are the only lights in the room, the entire color palette of the space transforms. I can go from a bright warm sunny day to a deep dark cool blue cavernous setting with a quick poke of my phone.

With the Hue system on my network and easily accessible on my phone, I became concerned about security issues. I’m not tripping over someone having fun and hacking my lights to do crazy things, as annoying as that would be, but the ease of accessing the hub feels like an open invitation to my network. That Chariot recognized that the hub was available and immediately started gaining access to it added to my paranoia. Supposedly, the set up is secure.

When I was done playing amateur armchair security expert, I set up Chariot to interact with the bulbs, which required a few seconds to bind specific lights to a location map on the screen. Once set, I was ready to play.

What you’ll like

A charming narrative hook

The protagonists of Chariot are two royal pallbearers following a command to take the body of a deceased King to its final resting place. The problem is that the ghost of the recently departed highness is still hanging around, shouting orders at anyone who will listen. And the unfortunate coffin-draggers happen to be the only ones within ear shot.

The King doesn’t want to be buried in just any old hole in the ground. He demands a spectacular plot that reflects his grandeur, preferably filled with rare stones. Monarchs seem to have a thing for being buried in, what are essentially, bank vaults.

The King’s self-centered, spoiled child-like banter with the voiceless pallbearers, who find themselves swinging from great heights and fighting off countless bandits, plays perfectly into the narrative-by-mechanics of the gameplay design. The royal pallbearers can’t proceed through obstacles without the King’s wheeled coffin, and the royal corpse most definitely will not survive without its loyal servants.

The King is a physical drag on the player’s progress, and he seems to find uncanny timing in complaining when his coffin is acting as a dangerous hindrance.

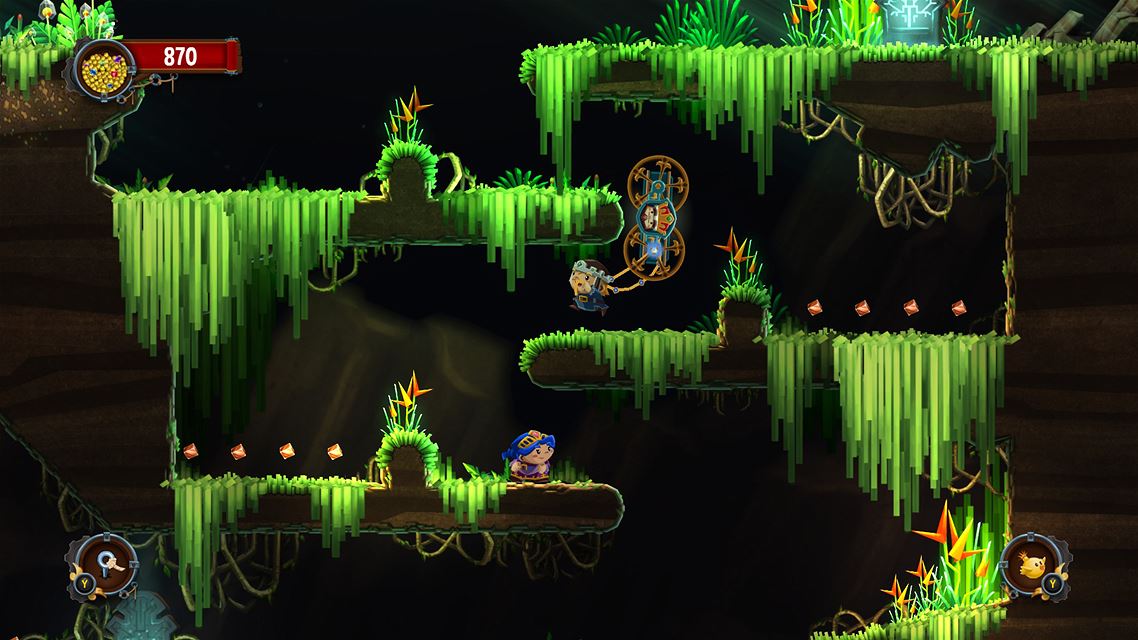

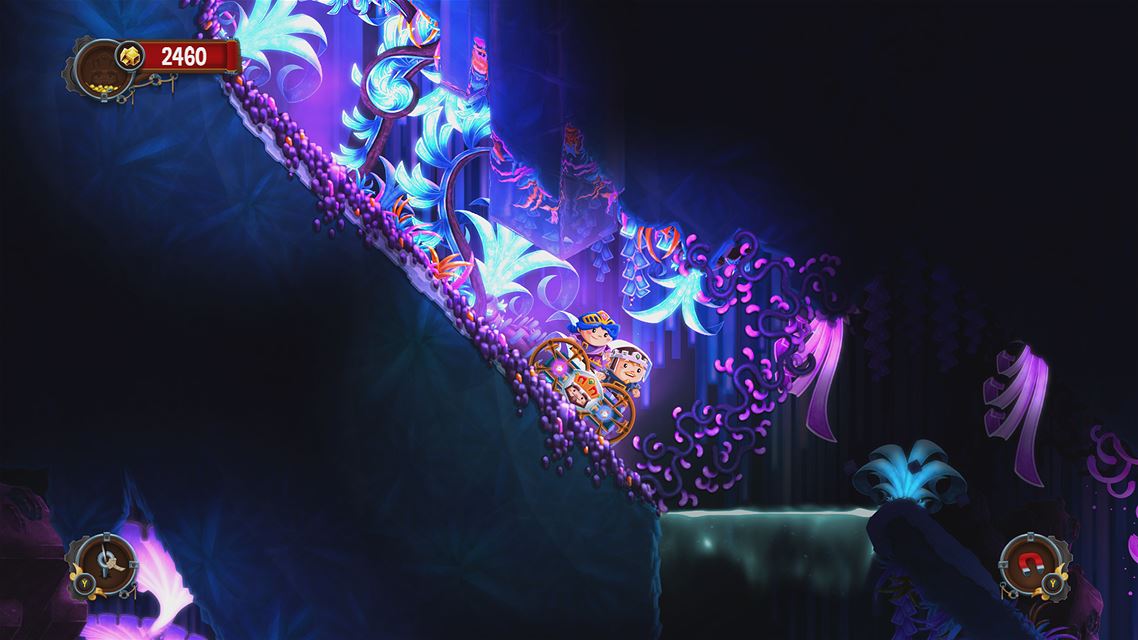

Beautiful art direction and use of the smart lightbulbs

Even without the Philips Hue lights, this game begs to be played in a darkened room. Especially if you’re a fan of color.

Levels are full of vibrant mood inducing hues and beautifully laid out compositions. Activating the Philips Hue lights add an extra layer of visual ambiance that no other peripheral can provide. When the servants are outside, the room suddenly blooms with the warmth of the sun and the clear blue skies of noon time in the spring. When the King’s coffin dives into the caves below, the room darkens with faint splotches of intense color.

The lights also interact with incidents that are happening on the screen. If I walk on certain platforms, the room will glow a specific color. When I hit a checkpoint, the room is blasted with a bright light. And when bandits are aware of our presence and begin attacking, the bulb closest to their spawn point will begin flashing red.

It’s amazing to me what these light bulbs can do to a completely black room and I think it’s a gimmick that Chariot exploits with great success. I don’t know that the game itself is worth the $100-plus investment to see this effect in action, but if you already have a set of lights, I think paying $15 for Chariot is a worthwhile way to see these bulbs interact.

An innovation in pallbearing

Chariot’s base mechanics are a reworking of the “defending the usable object” routine, where you must progress without letting go of an item of value. Yet you can also exploit these as a tool for moving forward. In sports, it’s often represented by the ball. In video games, it’s usually a second person. PlayStation 2’s Ico, a game where the protagonist must protect and use a little girl in order to solve environmental puzzles, is probably the Internet’s favorite example.

In Chariot, it’s the King’s coffin, an ungainly double-axle hearse whose wheels are slaves to gravity and inertia. The pallbearers can shove the vehicle in any direction and can sling ropes onto either side for pulling. Proficient platforming requires mastering shoving the coffin into situations where it can be used as a step or as a form of high speed transport.

Getting the timing and spacing down on whipping the ropes onto the coffin is important. You face many situations where the servant must act as a counterweight to the King’s dangling coffin, and visa versa.

It’s a fluid play against the world’s gravity and physics, and a play metaphor for the characters’ relationships, that becomes enjoyable when mastered. Every movement is responsive and there are no surprises when it comes to how the King’s coffin is going to react. What goes up, must go down. What I can pull, can likely tug back. In some cases, right over the edge of a platform.

Part of the secret to making 2D action games, as I have said countless times before, is to also nail a level design that understands a player’s abilities. When it comes to individual obstacles that the King’s funeral procession face, they can be extremely clever and ramp up in difficulty in a way that is not frustrating or intimidating. Nothing’s unfair about how these obstacles are set up, and at their most complex, they simply beg for a little experimentation in order to proceed.

But, when I look at these individual puzzles as a coherent level, I run into a severe problem.

What you won’t like

The pacing

After a grueling four-hour session of Chariot in which I thought I was making great progress, I was sickeningly deflated when the completion counter only read 18 percent. I don’t mind games with a lot of content. Hell, who would? Especially since we’re in an age of quick buck games and being nickle-and-dimed by DLC in order to gain a complete experience.

But with Chariot, I felt fatigued by the time I was part way through just the first chunk of levels. After a second rough go, I got maybe halfway through the second group of levels and squeezed out another 2 percent of progress. I was exhausted and wanted to do something — anything — else.

The level designers may have been clever at creating obstacles that take advantage of Chariot’s unique platforming mechanics, but when it came to the larger experience of these environments, they lack a sense of editing.

Chariot’s bite-sized moments of brilliance are smashed together in a mad man’s long distance marathon that doesn’t enjoy letting up for a breather. When I tackle a handful of obstacles and think I am near the end of the level, I find it keeps going … and going … and going. …

Adding to the infinite grind of these levels are pitfalls where a misstep would place me several sections back. It has checkpoints, but the spacing between them is often poorly thought-out.

My final frustration came when I had slipped off of a tricky ledge for the third time, which was just before the next checkpoint, which sent me hurdling down towards the last checkpoint every time. This wouldn’t be a horrible situation if the path in between didn’t take me five minutes of tedious tugging and swinging to get through.

Conclusion

Chariot nails a lot of great ideas. The platforming mechanics of dragging a rolling coffin around, swinging from ledges while holding onto the swaying vehicle as a counterweight, and using the cart’s inertia to successfully traverse clever obstacles — make for a unique experience. The colorful in-game art direction, including the well thought out plan for using the Philips Hue lighting system, also makes Chariot a gorgeous title. And the narrative for the first 20 percent of the game is humorous and charming.

But 20 percent is all I was able to get through.

This is an incredibly rare situation for me. My personal policy is to complete a game, as much as possible, before giving criticism. When it comes to reviewing 2D platform titles, I have never been in a situation where I could not 100 percent them before writing an article (and the turnaround on those is tight).

Yet the pacing of Chariot defeated me. The size and layout of the levels turn what should’ve been a large gathering of enjoyable challenges into a tedious slog, where after being teased with one false ending after another, I was just left begging for a break.

Score: 60/100

Chariot and the Philips Hue lightbulbs are available now. GamesBeat received an Xbox One code and a set of bulbs for the purposes of this review.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More