I’ve interviewed Cliff Bleszinski quite a few times in my career, but I noticed a little extra pep in his voice this time around. The game designer who’s most famous for his work on the Unreal and Gears of War shooter series has always been a high-energy kind of dude. But this time, he seems higher energy.

Perhaps I caught him at the right time of day. Or more likely, this is due to him recently returning from a two-year break — originally planned to be an early retirement — from the industry. You just get the sense, however, that he’s more excited about what he’s working on now than anything he’s done in quite some time.

He cofounded a new development studio, Boss Key Productions, and Nexon will be publishing its first project, a shooter codenamed Blue Streak (and you can read about how Nexon approached the deal here). With a background almost entirely in triple-A production, he doesn’t seem to worry at all that this will be his first free-to-play game. That’s Bleszinski: exuding confidence (yes, you can call it cockiness), even if it’s his first time in a new sector of the industry.

Energy plus confidence equals a rather long interview. Keep reading to get Bleszinski’s thoughts on:

- Comparing himself to Britney Spears

- The nightmares of working with big publishers

- How he’s changed as a game designer

- How the giant industry trade show E3 is going to die

- What books he read that helped shape his design sensibilities

- Wise words from hockey legend Wayne Gretzsky

- Insecurity among developers

- How the NFL, certain sci-fi books, and classic console games will influence Blue Streak

- What his weaknesses are

His time off

GamesBeat: Please recap for us why you retired a couple of years ago.

Cliff Bleszinski: I had been working, basically, since I was a kid, from having a paper route to working at McDonald’s and a yogurt shop to going to college and working on games all night long until I had enough money to drop out. I essentially grew up in this industry.

You know how when Britney Spears would go out and act crazy and get photographed by paparazzi and all that? That was me acting like an idiot at industry shows in my mid-20s, learning how to grow up and say the right thing and not come across as a child.

My point is that I was just tired. The industry was at such a massive tipping point. [Gears of War developer] Epic was figuring out how to do the new world order. I had saved up enough money to sit by my pool and get fat for a while, honestly.

GamesBeat: In the back of your mind, did you know that retirement would be temporary and that you’d be back in game development someday?

Bleszinski: The idea fountain hadn’t gotten turned off in the back of my head.

When I would travel or even take time off reading, I’d read about some interesting sci-fi weapon in a book, and I’d keep this idea in the back of my head and twist it around to see how it would work in a first-person shooter. Or different settings or environments, all that stuff. I had an idea in my head that married a universe and game mechanics together really well. I’m excited to start doing it.

GamesBeat: Did those seeds grow to the point where you knew you had to get back into it?

Bleszinski: I’m not even 40 yet. As much as I can enjoy sitting by the pool, it gets old after a while. I’ve taken up riding my bike, right? If I go for a superlong bike ride or a run, and then I sit down and play a game or watch a movie, it’s that much more relaxing because you did that work.

Anything worth doing in life is work. That’s why I’m more of a dog person, because dogs are a pain in the butt as puppies, but when they grow into really sweet dogs, you’re the one who helped mold that. The same is true of so many things in life.

There are two moments I want to play up. The first moment is when I put in my notice at Epic and I was getting ready to pack up all my stuff, and some build notes for Fortnite came through. An animation programmer had checked in some new animations for melee and some other tweaks.

I happened to see those build notes in my layout, and I was like, “Man, that’s one thing I’ll miss.” Getting the list and seeing what the programmers have put in, these new goodies to play with, firing it up when I get in, writing a bunch of notes, sitting down over the shoulder of one of the developers and going over tweaking this and reworking that. That’s compelling as a game developer.

The other moment was remaining friends with the guys at BitMonster, six guys who left Epic to go do mobile games. We’re having a pint with them in downtown Raleigh and went back to their office. We’re looking at the differences between Titanfall on an Xbox One versus a high-end PC — the lighting differences, the texture quality. That interoffice camaraderie is something that I didn’t realize I missed.

GamesBeat: Has that downtime given you any different perspective on game design itself?

Bleszinski: This was creeping in my head toward the end of Epic. I used to be about flash, about making people cry, about hitting that musical crescendo and all that. Now I’m all about systems interacting with systems. Traditionally I have not been a very good designer of that kind of thing. One of the positions I’m looking to fill at Boss Key is somebody who understands the crafting and implementing of deep systems like that.

It always goes back to getting to that [World of Warcraft publisher] Blizzard level of tremendous depth. I’ve played a lot of Hearthstone recently, and I know I’ve only scratched the surface after playing it for a dozen hours. It goes back to the greatest games of all time, like chess and go — easy to learn, a lifetime to master. That’s the pinnacle of game design.

Not having a project to promote, not having an agenda has allowed me to take a step back and look at where the industry is going more objectively. I went to [industry trade show] E3 for the networking, but I see the entire thing as largely a waste of money. It’s a model that’s eventually going to die. I see developers killing themselves for these stage demos, and that’s a moot point in this new world order that we’re in.

After having the time to stay outside of it and watch where things are going. It’s like Wayne Gretzky says. You don’t watch where the puck is. You watch where the puck is going. People say, “You’re doing free-to-play?” Yeah, because that’s where the puck is going. Let Microsoft and Sony fight it out and see how the consoles do, and maybe we’ll consider that at a later date. Not having an agenda has been tremendously freeing, creatively as well as professionally.

GamesBeat: Did you experience anything in your time off that’s changed or heavily influenced you? It could be something that you saw, a place that you visited, a game, movie, or book?

GamesBeat: Did you experience anything in your time off that’s changed or heavily influenced you? It could be something that you saw, a place that you visited, a game, movie, or book?

Bleszinski: It’s basically been reading. Let me grab my Kindle, and I can read you off a list.

I read the first book of the “Swarm” series. I read “The Lean Startup,” which was recommended if I was going to get back in the business. I’ve read some biographies. It makes you insightful about your own life and what your own art is going to be, especially as I’m going on what’s essentially act two of my professional career.

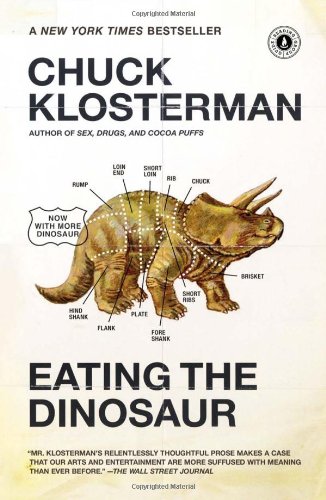

Let’s see. “Eating the Dinosaur” by Chuck Klosterman. “All You Need Is Kill,” before I saw the film [“Edge of Tomorrow”]. Sci-fi is in my DNA. As much as I like fantasy — I have this huge dragon tattoo on my back — I always go back to sci-fi.

The game designer

GamesBeat: Compare Cliff Bleszinski the Jazz Jackrabbit designer to Cliff Bleszinski the Unreal designer to Cliff Bleszinski the Gears of War designer to Cliff Bleszinski now, the Blue Streak designer?

Bleszinski: Phase one was throwing whatever you could at the wall and seeing what stuck — whether it was coherent or not, whether it made absolutely no sense. That’s the Jazz or Unreal phase. A lot of it, especially with Jazz, was taking what I like and twisting my own spin on it. There was clearly a lot of that Gunstar Heroes, Sonic the Hedgehog, Ristar vibe in what I was doing with Jazz.

When you look at the Unreal series, we always used this philosophy of zigging when other people were zagging. You can’t have a shotgun, but you can have the flak cannon. I have a saying – when you spend all your development time figuring out what players think you need in your game — things like standard shotguns — you’re not putting in the features that make your game unique.

Gears was caring a lot about gameplay but also caring about how cinematic it was. A lot of that — especially around 2006 and 2007 — was the result of a continued Hollywood envy, that insecurity that the video game industry suffers.

When I was at Epic and we’d have a weekly meeting and do Q&A, when the Gears movie was being worked on, the number one question from people was, “How’s the movie coming?” For the majority of those developers, it wasn’t cool enough to tell their parents that they made video games. If there was a movie based on their video game, suddenly there was legitimacy.

Going forward to where I am now mentally, for me it’s all about the player-to-player interaction. What kind of unique YouTube game-winning moments can this yield?

As we start to reveal the game’s design, a lot of that is tied to things that I’ve learned from watching pro football, becoming a big fan of football on Sundays. This isn’t to say I’m going to make a sports game, but there’s so much to be learned from the fan loyalty, the branding of the teams, the player personalities, the broadcasting, the rules of the game. Things like introducing randomness with that initial flip of the coin or the shape of the ball. All of those things are a massive influence on what I’m doing going forward — how we can get the most compelling player-versus-player arena shooter.

GamesBeat: It’s funny that you say that, because the last time I interviewed you, when you first went into retirement, you talked about getting into pro football.

Bleszinski: Here’s the thing. When you look at people gathering in bars to watch the World Cup — I don’t remember the World Cup being this much of a deal the last time. Maybe I just had blinders on. Maybe social networking wasn’t as big four years ago. But at pubs downtown in Raleigh, people who don’t normally watch soccer get caught up in it. It’s the same if you’re at a sports bar in North Carolina in March, getting caught up in the college basketball tournament. It’s the tribal nature of humanity. People want to be a part of something.

I was watching the enthusiasm of the fans at the Evo championships in Las Vegas last week. That’s absolutely amazing. The reason why people want to get into it is this tribal nature. It’s getting into something that everyone can be a part of, based on game experiences that are simple at first — anybody can kick a soccer ball — but when you look at the ultimate skill of the people who play in the World Cup or the people who play in EVO, there’s no real ceiling to how good you can be.

To have that level of skill, to make a game experience that allows for that — I want to get back to an experience where anyone can pick up a weapon and shoot somebody, but the right players can pull off stuff that will blow your mind.

GamesBeat: You said that you’re not building Blue Streak to be an eSports game, but it sounds to me like you might secretly love it if it blew up and became a huge eSports phenomenon.

Bleszinski: Anybody would love that. Everybody would love to make a MOBA [multiplayer online battle arena] that becomes an eSport right now. I like MOBAs. I appreciate them. I just don’t understand why everyone is still chasing them. It’s like my whole cola theory. You have room for Coke, Pepsi, RC Cola, and then everything after that is Publix brand cola, right? There’s only room for so much in that area.

So, would I love to make an eSport? Absolutely. I used to go to some of the Quake tournaments in Dallas and other places, watching people like Fatal1ty playing professionally. They didn’t set out to make that at Id. They set out to make the most airtight multiplayer game possible, and then the community rallied behind it, and then it made that magical leap. You can’t force that. Part of it’s the right place and the right time, but it comes down to making that airtight, easy to learn, difficult to master game that players can shine in.

GamesBeat: You’ve been honest about enjoying the fame and attention you’ve gotten in the game industry over the years. Do you think that’s changed you, either as a designer or as part of a larger creative team?

Bleszinski: It’s a blessing and a curse. It attracts a certain amount of talent, but as I build the studio, I don’t want to surround myself with a bunch of yes men or a bunch of sycophants. I need people who know when to question me at the right time and know when to let me do my own thing with the company.

From that end, when I left, I didn’t have the PR person on the call taking notes and cringing occasionally. I was able to be brutally honest about the state of the industry. For those people who were fans of my work and the things that I say, it bolstered their confidence. But at the same time, it created a certain amount of ill will among gamers who just wound up seeing a pull quote or a headline without reading the full explanation of why things are the way they are.

I’m now the one looking at the bank account. I’m the one calculating the burn rate. I’m hiring all these talented people, some of whom have children they need to feed. No pressure. You need to make a great game and build a great community that hopefully makes money for those employees you’ve brought on board and relocated.

One thing about being visible, though: It’s been extremely useful for attracting talent.

The new game and company

GamesBeat: Give us an idea of what we can expect from Blue Streak.

Bleszinski: I’m so tired of shooting tiny characters through iron sights when they’re so far away. You never get to see them. Part of it, we have things like big vehicles and mechs to blame, but part of it is the success of the modern military shooter.

I look at my multipage design documents for weapons and maneuverability, and there are still so many things that people either haven’t done recently in a first-person shooter or haven’t done at all. They date back to mechanics in Genesis and Super Nintendo games, relating to weaponry and player movement and things like that. They’d make for an absolutely fascinating take on a first-person shooter.

I’m not saying everything needs to go all crazy like Serious Sam or Ratchet & Clank, but there is absolutely a lot of room for some compelling stuff that can allow for some really cool trick shooting in a first-person shooter environment.

GamesBeat: For example?

Bleszinski: From what I’ve gathered from Destiny and Titanfall, they’ve started to scratch the surface of that. Destiny has a bit of a ground-pound move. You look at the double jumping and the wall-running in Titanfall. There’s so much more you can do with that. Things like the way certain platforming characters could dash. They could burst upwards or sideways. All these omnidirectional movements. Teleportation.

When you look at an arena shooter, movement can be so much more than just running and hopping. You look at the skiing from Tribes or the teleporting and rocket jumping in Quake and UT. I want the players to not be afraid of verticality in a first-person shooter.

One of the things Halo did well, especially in the early years, was stay relatively horizontal. Gears was almost completely horizontal. On a PC, though, I have a keyboard and a mouse, and things are going to get a little more Jumping Flash. That feeling of flying through the air and then falling down, the sensation of movement. It’s one-third of your arsenal at the very least: how you float through the world.

In Gears, cover helped the game as much as it hurt it. We wanted to go for the stop-and-pop thing, but players’ instincts to flow through that 3D world took over. They would roll, roll, roll. I don’t want to fight that. I want to embrace that sense of the first-person shooter zen flow of movement.

GamesBeat: If you weren’t Cliff Bleszinski, how would you like working with Cliff Bleszinski the game designer?

Bleszinski: First thing would be to get used to food and pop-culture metaphors when I try to explain what I want to see.

I can be a bit of a shotgun game designer. I just spray ideas out there. Figuring out what I want and how to make it the most fun — being a hands-on game designer as opposed to a system designer — is a fun but challenging thing.

GamesBeat: What’s it going to be like working for Cliff the CEO, then? The businessman?

Bleszinski: One of our company pillars is “no bullshit.” We’re serious when it comes to making games and being straightforward. We’ve been around the block enough to see corporate bullshit and call it when we see it. I’m going to make every effort to make sure that there’s none of that corporate crap at the company. It just gets in the way of making a great product.

As much as we know how to make great games and love making them, we also want to last. That’s important, as a studio and as a culture, to not forget. It’s a business, but it’s also the business of fun.

Case in point, some people I was getting close to hiring, I wasn’t able to work out something with them, or they went somewhere else. That’s OK. A lot of them I’m still friends with. Being able to separate that is something that I’ve had to learn from being the one who’s in charge.

But I already learned some of that from my partner in the restaurant business. We can go back and forth and have a heated discussion, and next thing we go back to friend mode. Not everyone can make that transition. I’ve learned more about business and finance in the last few years than I had in my entire adult life to that point.

GamesBeat: You’ve worked with big publishers before, so I’m curious as to what’s different this time. Before going with Nexon, why did you get feedback on all these different companies when you have so much experience yourself?

Bleszinski: It depends on the era. The Activision of the PS2 era is not the Activision of today’s consoles. Especially in the console business, when you look at the cost of making a disc-based game that people see as a campaign rental, your risk tolerance goes so far down. You get more and more of the traditional console executives treating their video game portfolio like they do their stock portfolio. Mitigate risk and diversify.

Nexon is very much a creative-first company. Give the creative people the ball and let them run with it. Check in occasionally and hope it makes that magic. When the time comes, we’ll see if we can make it on free-to-play and continue to roll out internationally. They’ll be there.

Some of the people I talked with in regards to working with Nexon, they said, “They funded us, and we didn’t hear from them for a year.” Tell me if any of the traditional old guard would act that way. Inevitably, at the old guard you’d have these mid-level executives who want to get involved. They want to tell you what genres they think will well. “MOBAs are big. We need one of those.”

GamesBeat: Blue Streak is going to be your first free-to-play game. I assume you’ve been doing your homework. What free-to-play games have you been studying?

Bleszinski: I started playing Dirty Bomb. I was playing Hearthstone. I don’t really like Facebook free-to-play or mobile free-to-play. I want to see if we can do pay-for-variety. One of the reasons people love League of Legends is that you pay for the heroes and pay for the skins. Or Team Fortress, or Counter-Strike: Go, which is fascinating with the gun skins. That’s still an airtight game, by the way.

It’s one of those things like calling something “open world.” What kind of open world? Are we talking about Grand Theft Auto, Fallout, Skyrim? Free-to-play for Candy Crush is completely different from free-to-play in Dota 2, which is different from Counter-Strike’s gun skin model.

What model we’re going to wind up with remains to be seen, but we’re looking at what the players care about that has the least amount of direct impact on player victory. My goal is to make it so that someone who hasn’t dropped a dime on this game will have a weapon that could kill someone who has spent $100 on the game.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that you wanted to work with the people at Nexon because they’re going to leave you alone on the creative side, and you can lean on them to learn how to monetize free-to-play. Don’t those two go hand in hand, though? At some point don’t you have to design to monetize?

Bleszinski: I’m with you. The key is to have the hooks in regards to what the game’s design is. The game can potentially be deep enough to not only be good but allow for free-to-play hooks. In regards to systems that can allow for a tremendous amount of variety in regards to weapon packs, things that can attach to them, cosmetics in player skins or weapon skins … if you have enough areas that you can silo into, they could later potentially have hooks, and you could start tuning that toward a monetization model.

Again, for each game it’s completely different. You can do it step-by-step on the PC, where you can issue an update every week and do A-B testing. I’m going to be straightforward and get a lot of feedback from the community.

I’ve never shipped a free-to-play game. I have a lot to learn in this area.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More