Hidden in last week’s batch of 100 approved Steam Greenlight titles is a little indie game with an unusual story. You could look at it and play it and not even realize, but for developer Jason Oda, it’s a reminder of the time he tried the Peruvian hallucinogenic jungle drug ayahuasca and, a couple days later, wound up stranded in the New Mexico desert.

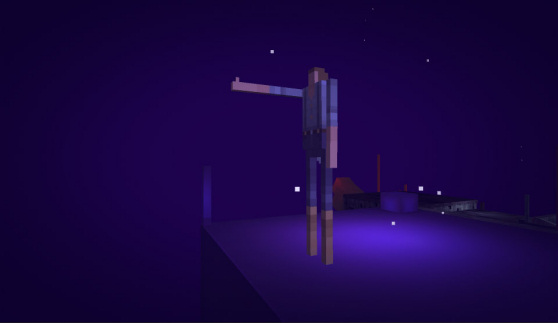

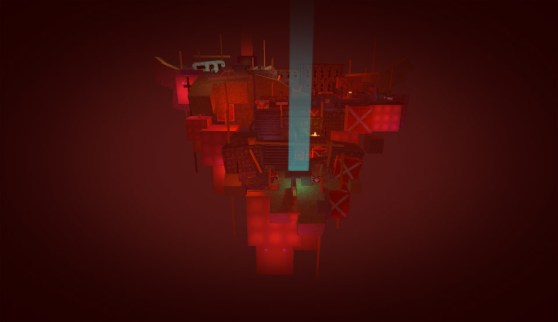

Continue?9876543210 (out for PC, Mac, Linux, and iOS) is about a dead video game character who wakes up in a limbo called Random Access Memory, where he tries to find some semblance of peace before the garbage collector inevitably comes and deletes him forever.

It’s a weird premise, but Oda has created odd titles before, such as the Zelda-esque Skrillex Quest, where you fight a glitch that has corrupted the world. (It’s really just a piece of dust on the game cartridge.) But I was surprised to learn (and Oda told me no one had really asked) that he made Continue? as a way to understand his own survival. When his southwest road trip earlier this year went wrong, all he could do was walk and hope to find shelter — or someone who could help.

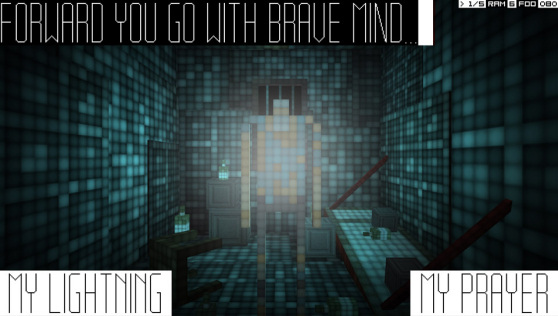

“Some games we play to kill time on a long commute, some we play at home to blow off steam after a hard day’s work, and some games are about escaping into a world more magical than our own,” Oda told GamesBeat. “I wanted to make a game that is meant to be played when a person is quiet and alone and sitting in bed late at night with a glass of wine or some weed, staring at the ceiling, thinking about their life.”

That kind of deep subject matter isn’t easy to convey in games, and Oda expressed some frustration over whether people are connecting with Continue? the way he intended. “They’re really stuck on the idea that it’s literally some kind of darker version of Wreck-it Ralph or something,” he said.

Humor and whimsy are part of Continue?, but its purpose is much more serious, philosophical, and “human” — so much so that Oda wonders if the medium can properly express it. He wanted to create an experience where abstract ideas aren’t nonsensical or meaningless, as in most games, but symbolic — so players can glean their own interpretation as they progress.

“Death in video games is common and forgettable, yet in our real lives, death holds an infinitely heavier weight,” said Oda. “I tend to be a bit of an existentialist, and I think the universe cares about us just about as little as we care about the lives of our dead video game characters. Continue? is about facing the disposable, meaningless nature of our lives and being at peace with it in a fulfilling way.

“… Rather than write a nonsense story about a dying character in some kind of a mystical purgatory, I thought it would be more fitting to imagine what happens to the millions and billions of characters in video games that die at our hands every day,” he said. “I thought about those little bundles of code that are blown to bits, fried by fireballs, or uppercutted into a pit of spikes.”

As players wander through Random Access Memory — a representation of our life and motivations — lightning periodically strikes, destroying the ground under your feet and thrusting you into battles down below. Prayer builds shelters where you hide from the garbage collector, buying you a little more time to continue your search.

Sometimes, players encounter abstract phrases, which are sayings that got stuck in Oda’s head during his drug trip. “One of them goes, ‘It is so hard, to find a good field, to lie face down in.’ In one of the randomly chosen interstitial parts of the game, a character walks into a field and lies face down as this mantra repeats three times,” he said.

“This little mantra for me represents the struggle we go through to find wonder and peace in the world, as well as the belief that it’s out there and worth searching for. Another person could choose to interpret this differently, but it being in the game is another example of a moment that encourages the player to interpret an abstract message and draw their own conclusions from it.”

In any single game of Continue?, players control one of six randomly chosen characters and encounter two to six of the 11 total areas. Some of these resemble the real places that Oda visited on his road trip, like the mining town in Clifton, Ariz., where he drove after some people helped him retrieve his car from where he had to abandon it in the snow — or a bar where he later thought about his life and felt thankful to be alive.

Oda tried to re-create those atmospheres. Each location in-game represent a different human desire.

“The idea is that each of us have lives that lean toward satisfying a particular set of desires,” he said. “These desires make up our ‘quest’ that we can see when reflecting back on our lives. … The explanation of what these places represent occurs just before you are deleted into nothingness.”

The developer is aware that this all might sound pretentious, but he hopes he can bring meaning to a medium that’s often shallow — to make people think about existence and life and how crazy it all is.

“When you take a moment to think about the things we do to get what we want, life can appear to be very stupid and bizzare,” said Oda. “For example, I need to get money so I can afford a haircut so that I can look nice, so that people will think better of me, so I can get love, acceptance, or a better job, which will make me happy and get me more money, so I can buy more haircuts … .

“When you zoom away, it can all appear to be very trivial and stupid, but really, these stupid pursuits of ours are all we have. And though we have to temper our greedy, less noble wants and needs, wanting and getting is all there really is to life. It’s so stupid, but really, it’s kind of beautiful, too.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More