Most adventure game protagonists talk to themselves. A lot.

Such is the case for a video game genre dependent on players observing and/or picking up everything for the purpose of puzzle-solving. For decades, intrepid adventurers spent a concerning amount of time rattling off mundane details about nearby objects to give players hints about their potential use, looking like a disconcertingly lonely person in the process.

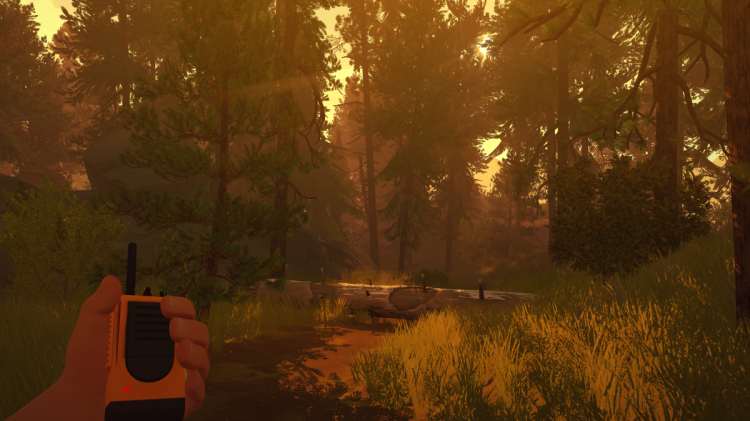

Firewatch (the exploration-driven adventure from developer Camp Santo coming to PlayStation 4, PC, Mac, and Linux on February 9) at least gives us someone to talk to. Newly hired national park fire lookout Henry meets and interacts with his supervisor Delilah through a walkie-talkie throughout the adventure, getting handy exposition and exploration tips from the other side of the radio.

But keeping your chief pair of characters on the opposite sides of a speaker presents its own challenges. So we recently chatted with Firewatch’s writer Sean Vanaman about how he went about bringing a relationship to life without those within it actually meeting each other.

Voices made for radio

The first step to realizing such a limited relationship, according to Vanaman, is casting. Having your main characters interact on a voice-only basis requires an actor with a specific skill set — skills that Vanaman and Camp Santo found in Cissy Jones and Rich Sommer.

“We knew Cissy Jones had the range to communicate emotions and meaning without having it be directly in the dialogue,” said Vanaman. “[B]ut it took us a very long time to find Rich Sommer. They both have such a subtlety of expression in their craft that it meant I didn’t have to overwrite. Sometimes I’ll just have them say ‘OK,’ but I spend lots of time directing them so they know what weight that ‘OK’ carries. And they’re just amazing actors, so they nail it.”

The actors weren’t the only ones limited by the physical distance of Firewatch’s central relationship. A strictly aural communication meant that characters lacked the ability to emphasize emotion in any kind of physical way, not able to “look away, storm off, [or] shake their head.” Performances had to be nuanced enough to be realistic but also straightforward enough to be understood through audio. Such a challenge ultimately proved to be an asset when it came to feelings of anticipation.

“I was able to re-create that feeling of being on the phone with someone, that bated breath of not knowing how he or she is going to respond,” Vanaman said. “You know, the thing that makes you not want to tell folks bad news over the phone. That became this great asset to the script, so challenges become strengths pretty fast if you’re thinking about them the right way.”

Delilah will remember that

Emotional consequences have played a major role in Vanaman’s game bibliography, particularly his work on the first season of Telltale’s lauded The Walking Dead adventure game series. Firewatch is no different.

“I think the game is rife with emotional callbacks,” said Vanaman. “[W]e wouldn’t put the actions in the game if we didn’t want players to think about them and expect ramifications. To do so would mean we were just making a sandbox, not telling a story.”

One of the most demoed elements of Firewatch has been an interaction Henry has with a pair of skinny-dipping women early on in the game. The two teens are rude and in flagrant disregard of several park policies, including setting off fireworks during a period of heavy fire warnings. As Henry, the player has the option to tell them off politely (or not so politely), steal the boombox loudly blasting music on the lake-shore, or drop said music player into the water. Delilah’s reaction to Henry’s handling of the issue will change depending on what action he took, and that’s if Henry decides to tell her the truth.

Vanaman isn’t committing to hard numbers when it comes to how far these emotionally loaded events go (and how many of them there are). But he did make a soft promise of dialogue options leading to noticeably different conversations, which will shape markedly different adventures depending on what you elect to say and the topics you broach.

“I don’t know what the math is, but I suspect hearing the same dialogue on multiple playthroughs, learning the same things would be very, very, very difficult,” Vanaman said. “You probably won’t hear the majority of the stuff they have to say, but the stuff you do hear will completely define your story. I don’t want that to sound too ambitious, but we don’t really get caught up in ‘there are x number of branches,’ there is ‘x breadth of divergent progression.’ We just sorta let the story expand and contract via player actions and choice as much as possible. It’s ‘yes, and’ game design.”

Emotional trigger

An often overlooked component of radio communication in games is the mechanical act of that communication itself. In addition to designing its walkie-talkie relationship, Camp Santo is attempting to emulate the physical act of operating a radio handset. When using a controller to play Firewatch, selecting a topic to discuss with Delilah requires that players press and hold the left shoulder button (the button on the same side of the controller as on the in-game walkie-talkie). Releasing the shoulder button selects the topic and gets Henry talking.

It’s not entirely how walkie-talkies work outside of Firewatch (real ones requires that users hold the button to continue the connection), but it’s enough of an approximation to get the mechanics across. And with this interaction taking the place of the usual X or A action buttons common to most console games, it does take some getting used to. Our brief time with the game at this month’s PlayStation Experience didn’t quite leave us aching to hop on the ham radio, but it did convince us to step further into our talks with Delilah. But for the road to (kind of) walkie-talkie immersion wasn’t an entirely easy one.

“That was the byproduct of lots of prototyping,” said Vanaman. “We just revved on it. We had some walkie-talkies around the office, so we held them in our hands and just thought a lot about it. I’m really pleased with the way it turned out. We tried it the ‘true to life’ way, but it didn’t have the same feeling. It’s more important to conjure the feelings of being real than to stick to the truth, I think.”

Radio play

We don’t always need to see a character to connect with them. Firewatch’s hope is that — through proper casting and a script that takes advantage of the anxieties of radio communication — we as players can explore Henry and Delilah’s relationship solely through audio.

Camp Santo has emulated — if not strictly replicated — the act of speaking over a walkie-talkie, and the developer promises both weighty actions and conversations. But it’s up to the player how much conversation is had at all.

At least, as adventurers, we aren’t talking to ourselves anymore.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More