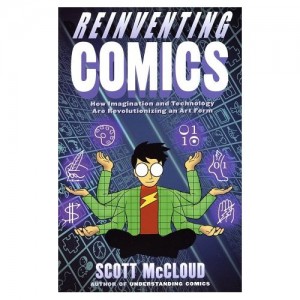

And I know… There’s a great book, I’m sure some of you guys have read it, called Reinventing Comics, by Scott McCloud. And in that book, he talks about… There’s a panel, actually, of a guy called Rube Goldberg, who… If you’ve watched The Goonies, or if you’ve played The Incredible Machine, he’s the cartoonist who pioneered these machine-creation cartoons, that was what he was famous for. There was a very similar conference to this for cartoonists back in the day, and this cartoonist came up to him, in this panel, with this… This was history. He was talking about how… “I feel that comics can be… They can tell stories, they can express philosophy, they can resonate.” And Goldberg was like, “You know, comics are knock-knock jokes, they’re vaudeville, you’re insane, don’t waste your time, don’t waste your life.”

You never want to be the Rube Goldberg of this argument, because you don’t want to be on the wrong side of things. I got into games because I wanted to merge movies and games, I thought there was a great opportunity to do that. But ultimately I started to realize that it didn’t work. I’ll tell you why I don’t think it works, first, and then I’ll tell you why I think it’s dangerous. I don’t think it works because… The first kinda hint of this for me a short-story teacher I had about 15 years ago. She said something that always stuck with me. She said that a great… Even a good story, a story that simply works, is one where you can… It’s a self-help book. And that doesn’t mean it’s a self-help book like you buy at a bookstore, and it doesn’t even mean… The reader shouldn’t be aware that they’re reading a self-help story. But it’s a story in which you can recognize your own humanity and get tools for living your life.

If you think of Indiana Jones, it’s certainly not a self-help movie, but he, or Rocky, is a character that we recognize our own vulnerability in. We also recognize the value of tenacity, of getting back up when you’ve been knocked down. You watch that movie, or you watch a film like Terms of Endearment, or Revolutionary Road, something that’s very sad or tragic, and even though you haven’t necessarily had those experiences, the nature of watching that film feeds your ability to say, “Hey, I’m not alone in the sadness in my life.” It gives you that energy to go back into the world.

To me, it’s almost like life is a freeway, and when you’re living your life, it’s akin to a simulation. Games are simulation. So if you get off the freeway to watch a movie, or to watch a show, or read a book, you’re taking a pit stop from life and digesting this stuff. You’re bringing this stuff into your life, and then you get back into life, and you use this, on an unconscious level in most cases, to make your life better.

But when you play a game, I think it’s more like living life. It’s not like watching a story, right? If you’re playing a game or living life, it’s like, “How do I go to the store to get all the ingredients I need to make the cake?” Or “How do I do what I need to do to put myself politically in the right position to get this promotion?” Or “How do I get this girl to go out with me?” Right? How do I do all these things? It’s very similar to resources management, spatial relation, interpersonal politics, trying to figure out… You know, I have these three objects, how do I get up to that cliff over there? If I’m Lara Croft or something like that? The brain is doing, in those cases… I think it’s much more similar, if not exactly, to what the brain is doing when you are living your life. That’s why I think that kind of pushing story language into life, or into games — which to me is the same thing, I don’t think the brain really distinguishes — I think it’s problematic and it doesn’t work.

I’ll give you another example. When you listen to Steven Spielberg, who’s one of my favorite moviemakers, talking about Private Ryan, he talks about the Normandy scene, which is very famous obviously. He says, “I didn’t want to use a dolly, I didn’t want to use a crane, I didn’t want to have any music from John Williams, I just wanted it to be guerrilla-style filmmaking, almost like the documentarians back in the day filming this for the newsreels, so it would be the closest to putting you actually on the beach.” But even with that desire, it’s not anywhere close to the same, and it’s not anywhere close to the same because you just have this… By the nature of watching it, the very nature of watching it, and the very nature of a director making choices, and the nature of you having a historical context of not just World War II, but your own life, you have this sort of omniscience, this… To get all Eckhart Tolle-ish, you have this kind of “Is-ness” of the situation. You’re above it, and you’re aware of it. You have enough brain ability to take in the lessons of it and the morals of it and the emotions of it.

But if you actually imagine yourself at D-Day, you’re probably not thinking of anything other than “How the fuck do I get to that rock?” If somebody came into this room right now and started spraying gunfire with an Uzi, we might think about our kids, we might think about our spouses, we might think about a lot of things, but the primary thing we’re going to think about is, “How the fuck do I get to the exit and how do I get out of here?” To me, that is how you think if you’re playing a good game, where they’ve made you actually care about your life, whether at a meta level or a moment-to-moment level.

And so I think… To me, when I realized that, it was sort of the beginning of going, “You know, this really doesn’t work.” But then it became even more important for me to question… “Why do I want it to work in the first place?” And not just me, but why are so many of us on this path to care…that games can be more? And I’ll talk about the “more” in a minute, but I want to talk about why I think this started. If you go back, and it’s kinda debatable, but I think they say the first game was about 4,000, 5,000 years ago. Some people say it was Parcheesi, but I think it was earlier that Parcheesi, but let’s just agree that it was millennia ago, was the first recorded game that was created. And all through millennia, you don’t see the people who created poker, or bowling, or the people who said, “Hey, we have to every couple of years change the rules in the NFL in order to adjust the game for modern times,” or what have you. None of them are saying, “Hey, you know what, let’s make a field goal worth four points, because that’s a reflection of the human condition.” They’re doing it because it makes the game better. It makes the game more competitive, it makes it more fun to watch, which is ultimately better business, and it makes it simply a better game. And so I started thinking, where did this come from? You don’t have a history of people making games all these years, trying to bring drama and human emotion to games, other than the fact that when you play a game, there’s human emotion in the nature of playing it.

I think it started in the early ’90s, really, when I started getting into games, and it started with two things that happened around there. One was CD-ROM, which was shipping games on CD-ROM, and that gave us two things. It gave us really elaborate cutscenes, and if you were lucky it gave you professional voice actors to do voices for your characters. If you weren’t lucky there were shitty actors. But you still had V/O in your games for the first time. So we were starting to see more cinematic trappings in our games. At the same time, you were seeing consumer-based 3D, whether it was the first PlayStation, or whether it was Alone in the Dark on the PC, early 3D graphics cards. And suddenly we could detach our camera from that 2D side-scrolling plane of Mario, or from the isometric view of Jungle Strike or Crusader: No Remorse, or the top-down locked view of Ultima. Suddenly we had all these beautiful cinematic camera angles, not just in the cutscenes but in the actual real time.

And I think we found ourselves kind of seduced by the language of film, the power of the language of film, going down this road where we were surrounded by the trappings of this. We started to think that… The expectations of film, we started to put them on games. And because they looked like movies and they were starting to feel like movies, we thought they needed to provide the same experience as movies. In that, I think we lost a lot of the fundamentals of what makes the medium special. Now, again, people disagree with me. And they’ll disagree with me real hardcore, like there was this lady… I really like her, she’s great, she wrote this great book called Smart Bomb, she was at GDC… It’s always GDC, or in EGM, I love EGM but they print articles about this, or on the internet ad nauseum, about how games should be more. “Developers are stunted adolescents,” is what she said. “You guys should be making games about the human condition, politics, why do movies do this, where’s your Citizen Kane,” and blah blah blah blah blah.