Neil Young has watched mobile gaming evolve on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, particularly since he sold his San Francisco startup Ngmoco a couple of years ago to Japan’s DeNA for $403 million. Now he is leading DeNA-Ngmoco’s expansion as it tries to become a worldwide entertainment giant born from mobile gaming. Last year, DeNA earned $1.4 billion in revenue, and it is now counting on Ngmoco and its NG Core platform to help make its mobile social gaming network, Mobage, into a global phenomenon.

Will DeNA’s success in Japan, where mobile gaming has exploded, repeat itself in the U.S. as smartphone and tablet games come to the fore? And will DeNA-Ngmoco be able to outmaneuver rivals such as Zynga, Electronic Arts, and Gree?

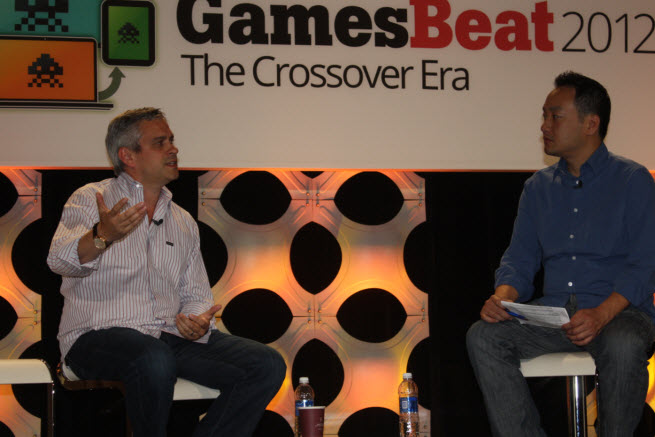

Young spoke at our GamesBeat 2012 conference in a fireside chat with Dan “Shoe” Hsu, editor-in-chief of GamesBeat. Their topic was about crossing over from one territory to another and the lessons that result. Here’s an edited transcript of their conversation.

GamesBeat: Why do you have to do more than just create a good mobile game to get it noticed?

GamesBeat: Why do you have to do more than just create a good mobile game to get it noticed?

Neil Young: It’s certainly true that you can detect a well-crafted game [and] that you can appreciate a well-crafted game. But it doesn’t mean that, scientifically, it’s going to appeal to a broad group of people or have the type of systems in place to make it a successful business.

GamesBeat: This seems to be a common theme that we’re hearing from a lot of people: that it’s not just about having the passion for creating games. You need to know your marketing and distribution.

Young: Yeah. It’s art and science, in terms of what you know. There’s a very simple equation at the end of the day. You’re trying to build a game that has a lifetime value that’s much higher than the cost of acquisition. If you can get that equation the right way around, you can afford to spend lots of money acquiring customers through mobile advertising or whatever mechanisms that you have available to you because every dollar that you’re putting into the software is returning something that is profitable. And then you start running into the challenges of just the scale of the market — how the dynamics of the market exist right now for the sort of app-buying spectrum.

GamesBeat: You have said that there’s a lot to learn from Japan and that user behaviors are pretty similar across the ocean. Would you recommend for a developer to, from the beginning, plan its game to go worldwide?

Young: No, I wouldn’t do that. You’ve seen the traditional console space — the number of Western games that work in Japan are very, very small relative to the number of Japanese games that are produced each year. And the percentage of those that make it in the West is very, very small. I think you should start with what you know, and you should make sure that you’re loading the deck in your favor by building something for an audience that you understand.

You should absolutely apply your passion to it and your energy to it, but you should also layer in the science. Observe what else is happening in the market and try to absorb as much of that as possible. So I wouldn’t try to build a worldwide game. I’d try to create a hit in a territory. And then what I’d try to do is — I would say, “What are the underlying things that make this work for gamers?” And then I would find a partner that really understands their market, and I would say, “OK, what do we need to do to take these underlying systems and repurpose them for the audience in a given territory?” It could be as simple as changing the art, or it could be as complex as just looking at the game design and completely rebuilding it.

GamesBeat: We hear from a lot of companies that have switched course. They say it’s difficult to work with a Japanese parent company or a Japanese counterpart just due to the cultural differences. Things they think will work here, people on the Western side might not agree, and vice versa. How did you overcome some of those barriers?

GamesBeat: We hear from a lot of companies that have switched course. They say it’s difficult to work with a Japanese parent company or a Japanese counterpart just due to the cultural differences. Things they think will work here, people on the Western side might not agree, and vice versa. How did you overcome some of those barriers?

Young: I think DeNA is a really unique company. It is not like any other Japanese company that I’ve interacted with before. It’s very entrepreneurial. It was founded by a woman [Tomoko Namba]. It has at its core this idea that the entrepreneurial spirit is very important, and that’s enabled it to kind of evolve and shift and change its business to meet the needs of the times. It’s not filled with chain-smoking 60-year-old Japanese dudes around a table. It’s exceptionally energetic. It has an amazing work ethic. Both in equal blends visionary and execution-focused. And so I think DeNA’s unique culture has enabled us to thrive. That’s the first thing.

The second thing is that it does turn out that there are cultural differences and [that] there are language differences. The thing that you have to learn to do is understand the intent of the people on the other side of the table. Often, we don’t spend enough time as individuals really truly understanding the intent of our colleagues. What we do is we react to the words that they say. That can become exacerbated if you’re in a situation where you’re dealing through translators. You have to operate with a degree of trust and patience. Time and time again, my colleagues in Japan have proved to me that they’re really great people who share the same vision that we share about the global opportunity in front of us. Once you fully believe in that, the words are just, you know — it’s just the words. The intent and the vision is the same.