On New Year’s Eve in 1996, Blizzard Entertainment inaugurated the action role-playing game genre with the release of the first Diablo. It was a massive hit and a novel experience. Diablo combined the procedurally generated dungeons and loot of games like Rogue, Moria, and NetHack with top-quality production values, a gothic fantasy setting, multiplayer, and fast-paced, clicky-clicky combat.

But it was 2000’s Diablo II that solidified the subgenre’s form—most current Action RPGs* are direct responses to the popularity and acclaim of Diablo II. D2 popularized four more major elements of the genre: an act structure, a competitive and cooperative online community, hardcore mode, and distinct character builds.

How we’re defining “action-RPG”*

We’re using action-RPG here to mean games specifically descended from Diablo, as opposed to RPGs that have action-based combat, like Mass Effect or Skyrim. This isn’t an ideal distinction, but genre titles rarely are ideal.

From those two games (which is not to say that there weren’t other Action RPGs in that era, just that these cast by far the longest shadow), we have the core elements of the genre, which almost every game today possesses:

- Procedurally generated levels: Each time you start, or sometimes even load, a game, the levels will be largely or almost entirely different in layout and creature distribution. As such, there’s rarely an expectation that you’ll see the levels more than once—whether starting new characters, replaying for experience or loot, or playing at a higher difficulty level.

- Procedurally generated loot: Action-RPGs have come to be known as “loot games,” where enemies drop randomized sets of items with procedurally generated attributes—like a “Lord’s Sword of Haste”—as a major part of the thrill. At the highest levels, these games continue to be viable and fun for seeking out better loot, from “Laz runs” of the first Diablo to the endgame maps of Path of Exile today.

- Click-based action combat: The basic setup of these games is that left-clicking you mouse does normal attacks, right-clicking does main special attacks, and using the keyboard brings in supplemental attacks. (In recent years, such games have started allowing players to hold down the button to continue attacking—as someone who gets repetitive stress injuries playing action-RPGs, this has been a godsend.)

- Top-quality production values: The fast-paced action combat has to be matched by onscreen clarity and both visual and aural feedback. Being good at depicting that’s happening, to keep players both informed and excited, is critical for these games.

- Gothic fantasy setting: Action-RPGs tend to take place in fantasy worlds, and darker ones than most games. This makes sense—they need excuses to have the player be motivated to slaughter foes by the hundreds, and necromancers and demons corrupting the world until a lone hero fights back works well for that. (There have been a few exceptions, but largely within games that are adjacent to the genre and probably on console: the superhero world of X-Men Legends, the postapocalyptic setting of Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel, and the high fantasy of Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance. I would like to see more thematic diversity in the genre.)

- Multiplayer and online community: Almost every action-RPG since Diablo allows small groups of four to eight players to join up and fight bad guys together. Many also include player-versus-player combat, though that’s very rarely any kind of game focus. With Diablo II and the expansion of Blizzard’s Battle.net service, it became a full online infrastructure for setting up teams and duels or trading items and tips

- Act structure: The stories of most action-RPGs since Diablo II has been three-to-five distinct acts, each taking place in distinct environments (in Diablo II: dark forest, massive desert, jungle ruins, Hell, and snowy mountain). Stories are usually slight and consist primarily of little more than explaining the backstory of the next dungeon or major enemy—action-RPGs rarely involve giving your player character enough personality that they can engage in any kind of meaningful non-combat confrontation or dialogue.

- Character customization: While player characters don’t have much personality in a story sense, most action-RPGs provide wide options for pragmatic customization. While the original Diablo only offered attacking and spells (making the Sorcerer a much more varied class than the Warrior), Diablo II made all of its seven classes have similar depth and multiple options for customization, both in skills you can learn and core attributes with choices given at each level-up.

- Hardcore mode: The old roguelikes that Diablo was partially inspired by were famous for their permanent death—once a character died, they were gone forever. While the original Diablo didn’t have that, it was present in Diablo II, and it has consistently been an option in most games within the subgenre.

This is a surprisingly strong subgenre of games, with several excellent and varied recent installments. We took a close look at a few of them: Torchlight II, Diablo III, Path of Exile — and a broad look at several of the rest.

First up is the elephant in the room.

Diablo III

Diablo III’s initial problems were well documented: Server stability issues, an overbearing plot, poor loot progression, excessive difficulty, and the damnable auction house all served to give it a poor reputation. That was unfortunate for two reasons: first, a really good game was underneath the meta-game issues; and second, almost every patch since and the Reaper of Souls expansion have worked to eliminate DIII’s major problems.

Describing what actually worked about Diablo III presents some difficulty. It’s easy to look at meta-game systems like loot progression, but it’s much tougher to analyze what makes the individual animations of a shield bash superb. The sound and animation are all top-tier, with those Crusader Shield Bashes landing with satisfying thuds, while the Demon Hunter’s escape trick “vault” blurs across the screen with a nice little “whoosh.” As the game progresses, the situation onscreen becomes increasingly complicated with meteors falling, lightning hammers flying around, and bosses throwing up walls, but Diablo III always does just enough to feel comprehensible. The interface helps, too—all kinds of little things, like holding down the mouse button continuing to fire at the original enemy, even if it’s ported to the other side of the screen. Just fighting is incredibly satisfying. It’s also been ported to consoles and their controllers, to wildly successful reviews.

This is fortunate, because Diablo III has evolved into a game entirely focused on combat. The encounter design is effective for calling multiple groups of enemies together, turning fights into mobile, dynamic affairs, especially when multiple bosses get into place. The “Adventure Mode” added with Reaper of Souls, meanwhile, pushes the plot to the side and encourages consistent fighting. Finally, the controversial skill system, where every ability is available but only six can be used at once, works extremely well at allowing combat to be manageable even in chaos.

Those advantages come at a slight cost—Diablo III isn’t that good at creating a sense of character progression and history. You select whichever skills you feel like choosing, instead of building a powerhouse over time. Adventure Mode cuts out the repetitive story, but you just zap around the world with no sense of place. And the difficulty levels are player-centered—if you’re having a too-easy time, raise the level!—but that makes it tough to have a sense of accomplishment at getting to the next difficulty level, as the series used have.

If you want to focus on the “action” side of the genre, Diablo III is almost impossible to beat. But for a more satisfying, progress-centered take, Torchlight II is worth a look. …

Torchlight II

The most direct successor to Diablo II on the market today isn’t its sequel Diablo III. The Torchlight games have carried on that form, with several tweaks.

The most immediately noticeable aspect of Torchlight II is how colorful it is. In terms of story and setting, it has a similar tone to most other games in the genre (a hero from the previous game being corrupted and destroying all he touches is almost an identical story as Diablo II), but it does so with cartoonish bursts of color—bright blue ice-beams and red cannonballs. It’s not atonally garish, but it is immediately recognizable and compelling.

Torchlight II’s biggest selling point is its sense of character progression. Like Diablo II, TLII has distinct classes, each with multiple build possibilities. Each also feels distinct and exciting—an ice Embermage or a dual-pistol Outlander—I found myself rolling 10 characters so I could potentially play each one. Torchlight II also makes room for different decision-making while creating the characters. The distinctive visual style helps here as well—I was putting together a cannon Engineer when I realized that I’d created a sort of steampunk Big Daddy from BioShock.

Another major distinction for Torchlight II is its mod support. It’s even got a Steam Workshop page, which includes little things like minor interface tweaks as well as massive additions like SynergiesMod, which includes a robust endgame, or the Far East expansion which adds items and classes based on East Asian history and culture.

Torchlight II also plays much like it looks: fast and fun. This is a game built around running from place to place, finding massive groups of monsters, filling the screen with shiny destruction, and moving on. The controls and combat are a little looser than Diablo III, particularly in terms of sound effects feeling distant, but it doesn’t get in the way of combat feeling satisfying.

Continuing on the path of character customization leads to the next game: Path of Exile.

Path of Exile

It’s possible to imagine the three big action-RPGs existing on a linear scale, descending from Diablo II. In the middle is Torchlight II, a direct and balanced attempt to build off the classic. On one side is Diablo III, focused on moment-to-moment gameplay and smooth, high-quality player experience above all else. On the other side, then, is Path of Exile, an independently produced free-to-play action-RPG that’s built around customization and mastery.

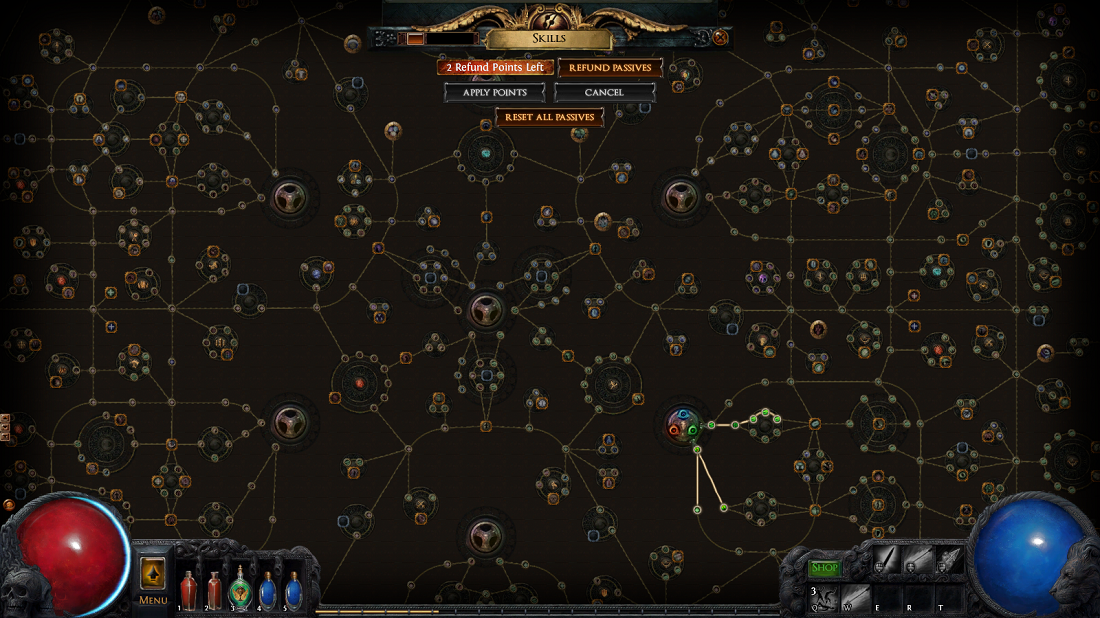

Path of Exile’s great appeal can be seen in a single image: one of its skill trees. This massive construct looks a lot like Final Fantasy X’s Sphere Grid, but unlike that game, Path offers legitimate choices from the beginning. Starting as a Witch (the mage class), the first few levels involve adding to the Intelligence attribute or building up energy shields. But a few levels later, new areas open, like increasing Dexterity and Strength, giving the opportunity to build any class in any particular direction.

Skills improve in a similarly open fashion: Each skill is tied to a gem, which can be found or traded for throughout the game. Every equippable item can have colored slots that the gems fit into, so you want to be looking for gem and item combos that will work. (The gems can also pair with one another, calling to mind another Final Fantasy, VII and its Materia system.) While the quest reward gems align with class early on—magic for mage classes, melee for fighters, etc.; spending a little more time acquiring gems gives you a much wider variety to build a unique character with.

But Path of Exile’s customization options inherently lead to the issue that the game can be unfriendly to newcomers. It’s not immediately clear which skills and attributes are most important, and this could lead to some failed character builds. This unfriendliness extends to other aspects of the game; for example, the inventory in Path of Exile holds maybe 10 equippable items—somewhat similar to the original Diablo—while its competitors offer significantly more convenient inventory management. But convenience simply isn’t a goal of Path like it is Diablo III—they’re ideologically opposed.

It’s fortunate that Path of Exile offers so much in terms of meta-game customization, because it definitely lags behind its competitors on technical. It looks and feels clunky compared to other action-RPGs. For example, a constant attack spell in Path of Exile like Lightning Tendrils works like this: You press the attack button, and the character casts the spell for a couple seconds in the direction you’re pointing. If you hold down the attack button, the spell repeats. If you move the mouse so the attack changes, the spell casts again at the new angle when it completes after the old. In Diablo III or Torchlight II, casting a repeating spell like that allows constant pivoting—moving the mouse around your character in a circle while holding the button down makes your character turn in that circle, attacking all around. This doesn’t mean that Path is unplayable, but it’s much more focused on the “RPG” part of the genre than the “action”

Path of Exile does have one of the best story/theme connections of the main three action-RPGs. In it, you play a criminal exiled to violent continent and help its developing communities learn about the land and create safe havens. This manifests in interesting ways outside the story, like a lack of direct in-game money. Instead, you sell and buy via barter, using things like Identify Scrolls or gems that buff armor. (Out-of-game money is spent on cosmetic effects, with no pay-to-win.)

Path of Exile has several clever systems like this, but it can be difficult to switch to after the crisp combat feel of Diablo or Torchlight. Picking Path of Exile becomes very much about prioritizing full customization and free-to-play options.

With the big three down, there are also several other relatively recent action-RPGs out there. …

And the rest

Grim Dawn: Grim Dawn has been making its way through Steam Early Access for a while now, but it’s certainly got the feel — if not the content — of a fully-formed game. It’s not as slick as the most recent Torchlight or Diablo, but it’s slightly more reactive than Path of Exile, although not as focused on total character customizability.

What sets Grim Dawn apart from most other action-RPGs is its focus on the campaign. Most games of the genre use quests and storyline purely to maintain forward progression — here’s the reason you have to go to the next zone. Grim Dawn’s model is closer to other RPGs, like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim or Dragon Age, where you get multiple quests in similar areas, and try to efficiently cross them off and gain their rewards. As such, Grim Dawn is probably the most self contained-feeling game in this, where the impulse is to progress through its narrative instead of progressing through its systems.

Borderlands: The Borderlands games are one of the biggest divergences from Diablo, but they’re worth mentioning because their loot model particularly is so Diablo-inspired. They’re first-person shooters that drop piles of randomized guns on players who build up customized characters in what should be a co-op mode. They’re not procedurally generated in terms of level design, but the embedded levels are filled with personality.

But Borderlands struggles with the application of first-person shooter gameplay to an action-RPG structure. The FPS is heavily reliant on player skill, while RPGs are built more around the skills of the character. As such, both Borderlands games can veer wildly in difficulty, where the combination of skill, level, and items doesn’t always fit together into a coherent whole — although the second game is significantly less frustrating in this respect. But if the loot aspect of the action-RPG that’s exciting, this is a good variation.

Din’s Curse: Din’s Curse comes from the days before Unity and other accessible, good-looking 3D modeling development tools, and it shows. This is not at all a contemporary-looking, or feeling, game. But if you can get past that, Din’s Curse has strategic depth and procedural randomness at a level beyond almost any other action-RPG — you have to defend your town from attacks as well as normal journeys.

X-Men Legends/Marvel Ultimate Alliance: Whatever licensing agreements have stopped the Legends/Ultimate Alliance games from being digitally distributed is unfortunate for players, as these are fast, fun, and occasionally deep superhero action-RPGs. There’s not a whole lot more fun in the genre than having Colossus pick Wolverine up for a fastball special. These are very much worth looking up if you can find them.

Marvel Heroes: This more recent offering theoretically serves as the next step after the Legends/Alliance games, but in going more massively multiplayer and free-to-play, it’s lost much of the controlled linearity of the earlier games. In other words, Marvel Heroes plays loose — like it’s more about finding a particular skill and exploiting it than constructing a character and understanding combat options.

But Marvel Heroes does offer a great deep dive into the Marvel universe. Beyond Captain America and Iron Man, there are also Kate Bishop skins for Hawkeye or playable side characters such as Squirrel Girl or Taskmaster. And it may not be balanced, but there’s not much more satisfying than finding a plaza full of bad guys as Daredevil and tossing a bouncing baton that critically hits all of them with a “ping, ping, ping” and cashing in on their loot.

Titan Quest: If you’re looking for a game that bridges the historical gap between Diablo 2 and the current crop of RPGs, Titan Quest may be the best bet. Its combat and space design feels similar to the controlled chaos of Diablo 3, although the customizability and variety in its skill system feels much more advanced than D2’s, and closer to Path of Exile and Torchlight 2. That said, Titan Quest’s interface and battle control feels decidedly archaic, with multiple clicks involved in targeting tiny spells. Another notable attribute of Titan Quest — its Greek mythology setting is dramatically different from the usual gothic fantasy of the genre.

Sacred 3: The Sacred series has been around almost as long as Diablo, but its reputation has taken a serious dent lately with the poorly reviewed latest installment, Sacred 3. All three installments are easily accessible digitally, however, for another view of the history of the genre.

Victor Vran: Very recently out of Early Access, Victor Vran is notable for accenting the “action” part of the genre dramatically, offering twin stick controls via either mouse+keyboard or a controller. What’s more, it does it shockingly well — controls are taut, and combat paced for quick, interesting choices for movement and weapon/skill choice. The metagame, meanwhile, presents specific goals for using all of its mechanics — finding secrets, using different weapons, killing quickly. Victor Vran has a few writing annoyances, and it’s a constrained game with none of the “you can play this forever” feel of the main three games mentioned, but it’s a worth mention.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More