Primitive shapes

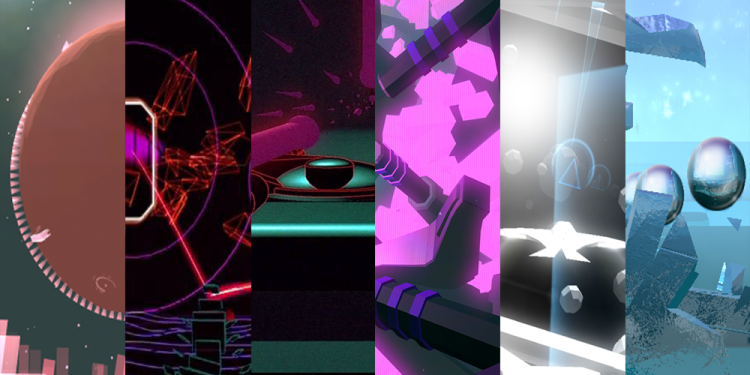

Digital Futurism’s roots are strongly tied to the aesthetic limitations of early computer graphics, which have caused a distinct visual style of exposed construction in some of its worlds. For example, the edges of 3D models are rarely smoothed, revealing the hard planar nature of the polygons that construct the object. In other cases this effect is taken a step further, highlighting the edges and revealing the topology of an object’s mesh.

These are things that artists working on today’s realism focused titles would go to great lengths to hide, but in Digital Futurism the basic building blocks of 3D computer art are highlighted and celebrated.

Filippo explains why he finds this aspect of Digital Futurism more appealing than other photo realistic art directions. “I think there is an honesty to the style that feels refreshing. I, myself, have grown completely tired of 3D art attempting, and mostly failing, to look photo realistic. When it comes to some 3D games or CGI movies, I honestly can’t understand why they didn’t just film actors.”

Flanagan follows a similar line of thinking, but goes further into his opinion on the photo realistic polygonal pipeline. “I can’t speak on behalf of other games using a similar visual theme, but for me it’s a result of a kind of love/hate relationship with polygons,” Flanagan says. “I think they’re beautiful and are an awesome result of the sacrifices we made in order to achieve early 3D graphics, but as a workflow to achieve photo realism they’re kind of all wrong in my opinion.”

Flanagan explains his perspective making a comparison to vector art, “It’s a bit like hyper-real vector art … it’s an impressive technical achievement, but outside of a few useful edge cases, why do we bother? There are a lot of parametric modeling and design methods that seem much more geared towards actual creativity and not pushing vertices around, but I think we’re a good ways a way from doing that stuff in real time.”

Digital Futurism’s embrace of low-fi 3D objects exposing their basic polygonal construction also allows for a style of purposeful abstraction. The history of video game art is a history of digital minimalism and abstraction, as the limits of real-time rendering made it necessary. For example, a square pixel in an Atari 2600 game could be anything: a bullet, a ball, maybe even a power pellet. Mario’s sprite in the original Super Mario Bros. is an abstract shape of a cartoon Italian plumber. We see Mario because he is being suggested with intelligent use of a severely tight pixel limit. In today’s Digital Futurism, abstraction is done primarily for artistic expression and has less to do with working within technical limitations.

Filippo touches on this change. “When I play a game that isn’t trying to hide the vertices, it just feels more pure and intentional. I think that the representational style also provides a better foundation for storytelling. Every art form relies on the imagination of the person experiencing the art — and some forms engage the imagination to greater extent than others. Representational visuals often make the brain fill in the blanks, so to speak, and force a deeper sense of engagement.”

Flanagan shares a similar viewpoint. “I feel as though polygons are a direct nod to the medium — the ‘transmission mechanism’ of digital games,” he says. “There is something undeniably romantic about that idea to me and perhaps speaks to your [Stephen’s] perception of the construction of objects. That and the fact that this polygonal look can more-or-less only happen in virtual worlds is exciting and should be celebrated more.”

Flanagan also points out a creative advantage to going this route, “It’s also a lot further away from any uncanny valley or suspension of disbelief dissonance that could otherwise ruin the experience … assuming the player can become comfortable with the polygonal look to begin with.”

Righi Riva, however, strikes at the core of the issue. “We also think there’s something related to the nature of the 3D objects as pure abstract objects though. Like in painting, one can make use of colors in a very elaborate way, to produce realistically looking images, or use them more plainly to achieve pure monochromatic abstraction.”

Righi Riva illustrates the difference between the two creative philosophies. “In the first case, we almost forget about the medium we are using in order to deceive the eye of the viewer,” Righi Riva says. “In the other case we are explicit about the medium that we are using, the artwork participates in the debate about the nature of the medium itself. So when we use 3D primitives or make the polygonal nature of 3D objects visible, it is because we believe there’s a genuine quality in the raw nature of polygons that makes them visually compelling and expressive.”

Working within the confines of low-fi can also provide different visual tricks for the artist to use, as Righi Riva points out, “…working in low poly[gons] is a limitation that forces artists to condense meaning, creating iconic forms. That is always a surprisingly rewarding exercise! As far as recognizing primitives into more complex object, there is a compelling psychological theory that involves Geons as fundamental units of understanding 3D objects, that is worth looking at!”

The theory Righi Riva mentions is known as recognition by components. The basic premise is that the human brain recognizes certain complex objects by breaking them down to their basic shapes, known as Geons. These Geons are then stored in our memory. So when we collectively think of a wagon, we see a rectangle for the base, four cylinders for the wheels, and a long rectangle for the handle.

Righi Riva also explains the concept of shapes built out of hard planes being more readable than those with smoother gradations, “Finally, a rendering that feels realistic and physical, is harder to achieve on a soft edges, smooth normal model. There is a counter intuitive property in play, where more abstract looking materials and shapes are more believable as hard, crystal-like objects, than they are when they are supposed to look soft. In other words, non low-poly representation shows the technological limitations more as faults than features of the visual style.”

In part 2, we dig a bit deeper into the low-fi nature of the movement and how it relates to the prototype stage, its influence on audio in the video game medium, and our guest developers’ reasons for choosing to work in this art style.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More