Electric rhythm

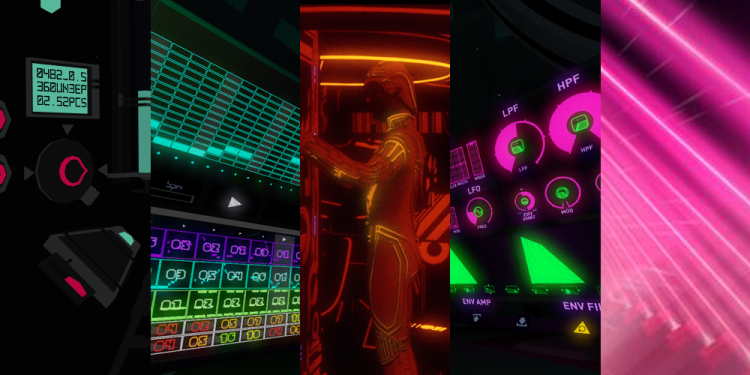

While a specific style of audio design doesn’t accompany Digital Futurism, I have noticed that music-heavy game designs seem to gravitate toward this art style. The precursors to Guitar Hero: Harmonix’s Amplitude and Frequency, are heavy adopters of this visual aesthetic. Rez also contained gameplay that manipulated the audio heavily based off of how well you were doing.

I realize that none of the games discussed here involve audio to the same degree as these examples, but I still wanted to get their perspective on why audio-centric game design seems to gravitate toward Digital Futurism.

Henrick Johansson, artist on Smash Hit, understands its impact. “On an emotional level, you’re in this abstract other worldly setting. If you have music that resonates with that setting, you can create a powerful experience that feels immersive,” Johansson says. “I think it’s just being so different from reality that makes it work so well with music.”

Flanagan suggests that it may have more to do with the nature of working in a visual style that demands legitimate intent. “If a designer is developing a game with this aesthetic theme, they are already taking a risk for the sake of imbuing their project with something very intentional and deliberate,” he says. “I would assume that other aspects of the experience would be treated with similar consideration, whether it be sound design, music, UV, or narrative. That’s not to say photorealistic games can’t do the same, or digital futurist games don’t phone it in from time to time either, so perhaps that’s a bit of a leap on my part.”

Filippo, however, hints that Flanagan may not be taking as big of a leap as he thinks. “For Race the Sun, we used an intentionally stripped down soundtrack that may not be what you would expect for a high speed game,” Flippo said. “We’ve gotten lots of compliments about the music, which at first was really surprising. Then we realized that the simplified graphics and controls allowed the music and sounds to take a larger role in the overall experience.”

It’s Righi Riva, again, that digs a bit deeper into this theory. “I think it’s more of a factor of being generally more aware of the aesthetic implications of an artwork that leads to a more conscious audio design effort,” Righi Riva said. “We don’t particularly find a direct connection between dedicating a lot of attention to the auditory experiences our games provide and this particular art style.”

“If we had to guess, we would say that people with similar sensibilities to ours will tend to also think a lot about the sound landscapes, understanding that what makes a game world is not a linear sum of the components ‘audio plus video plus interactivity’ … but rather a synesthetic convergence of these elements that directly influence each other. It is a bit of the Kuleshov Effect idea applied to multimodal representation.”

The Kuleshov Effect that Righi Riva mentions is a cinematic editing technique that Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov came up with in the early 1900s. Kuleshov took a static close-up shot of the famous silent-era film actor, Ivan Mosjoukine, staring into the camera with a blank expression. Kuleshov then shot footage of a bowl of soup, a child laying in a coffin, and a beautiful woman. He edited all of these shots together, with Mosjoukine’s stare coming before and after each shot. The result is that the bowl of soup, the coffin, and the woman had audiences implying an emotional expression to Mosjoukine’s blank stare. In this case, they thought he was expressing hunger, despair, and lust.

Alfred Hitchcock also explains the phenomenon.

In the case of Digital Futurism, maybe the low-fi visuals of the low polygon art direction naturally strengthens the audience’s reception to specific types of audio?

Righi Riva appears to be heading towards that conclusion, “It is possible that a more low fi, less visually rich or intensive experience allows for more integrative and expressive soundscapes…balancing out the bareness of the low-poly environments.”