Being obsessed with video games often nurtures a certain amount of jadedness and pessimism for the industry. Is it any wonder?

Publishers run too many media campaigns that promise more than they can deliver. Developers release buggy games that miss deadlines and require major day one patches. Game executives are obsessed with finding new ways to squeeze every last dime they can out of us. Interactions with other players can become a depressing revelation of the ugliness of the human condition.

But what if I told you that we have plenty to be thankful for as well? I know, I know. It feels much more therapeutic to be negative and vent, but it’s Thanksgiving, damn it! Let’s adopt a glass half full attitude to things for at least one day a year. Trust me, when you change your perspective, you’ll find there is a lot to be grateful for right now. Let me show you.

Good fighting game sticks

You know what fighting sticks were back in my day? Blocks of wood that were drilled to fit big American sticks and buttons, with a rat’s nest of wires and a loosely dangling printed circuit board from a console gamepad acting as the brains of the operation.

If you preferred Japanese-brand arcade parts, like Sanwa and Seimitsu, tough! No one on this side of the world carried those items with any sort of regularity, and if they did, you were paying a premium for it.

So the next time you see a Hori or MadCatz fighting stick, be grateful that they decided to flood the Western fighting game market with fighting sticks using Japanese hardware.

Broadband online play

This may sound like someone talking about the wonders of the portable telephone or the horseless buggy, but there was a time when the Internet wasn’t accessible for the majority of consumers (before the great flood of AOL discs). This meant that unless I had friends over to play, every console game was a single-player experience. If I wanted competition, I had to go outside, catch five buses, and walk a mile in knee-deep snow to get to an arcade.

Now? Hell, I don’t even have to roll out of bed to play against a human opponent. And the supply of players is endless if I am playing a popular competitive title.

The Internet changed a lot of things for humankind, both good and bad, but the capability to connect and play against each other is a comfort that goes almost invisible today. That is, until PSN or XBL go down … then suddenly, everyone’s lives are ruined.

Online marketplaces

Being able to connect a console game to the Internet and play with friends has been around for a while, but the idea of the digital marketplace for games only really hit maturity in the last few years. Back in the days, if I wanted to purchase a game, I had to go outside, catch ten buses, and walk five miles in neck-deep snow to get to the store.

Now? Hell, I don’t even have to get out from under my covers to make an impulse game purchase.

The digital marketplace provides a lot of amazing values to every facet of the game industry pipeline as well. Publishers get a cut of every sale and don’t have to set aside large chunks of cash to deal with manufacturing and storing physical product. Indies can share the same sales space as the large guys, and consumers have a game that is available for purchase and experience forever (well, in theory).

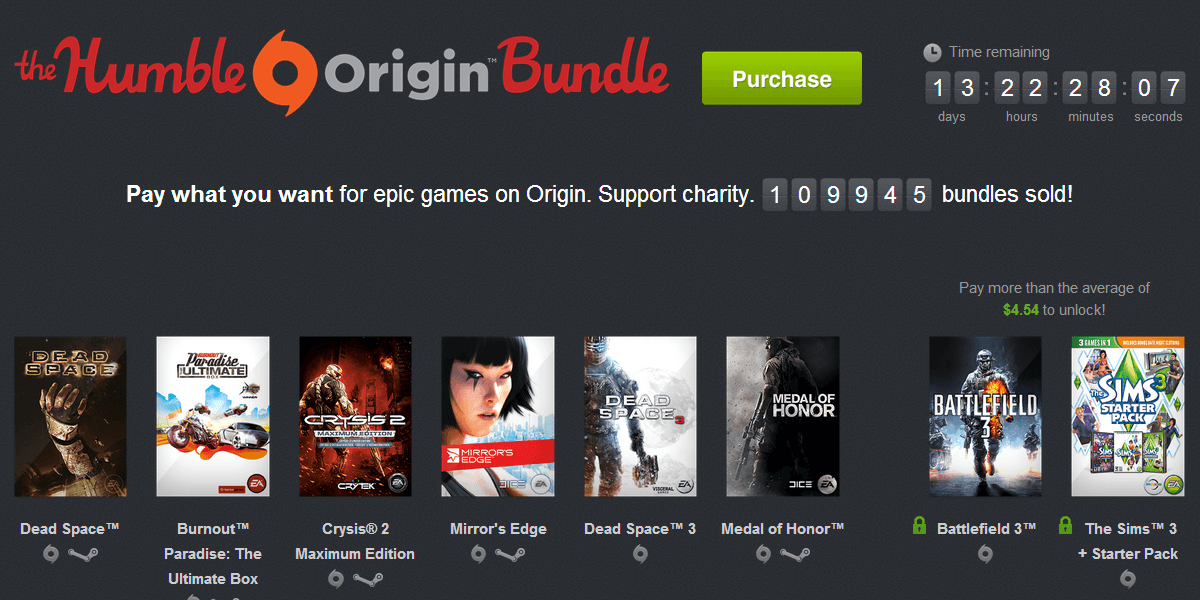

The bundles, humble or otherwise

The bundle theory is one of the craziest sales campaign ideas I’ve ever run across. Consumers see a group of games that they can purchase for any amount they want. It should be one of those “it’s too good to be true situations,” but amazingly, it isn’t.

Before this concept launched, if you were too cheap to snag a game at its lowest retail price, you had only three other options: steal it, borrow it, or pirate it. Depending on your perspective, two of those are the same thing. To some game execs, there is no difference between all three.

The bundle theory essentially gives the consumer zero excuses for not throwing down something, anything, for a game they are willing to play. Some of these bundles cost as little as a buck.

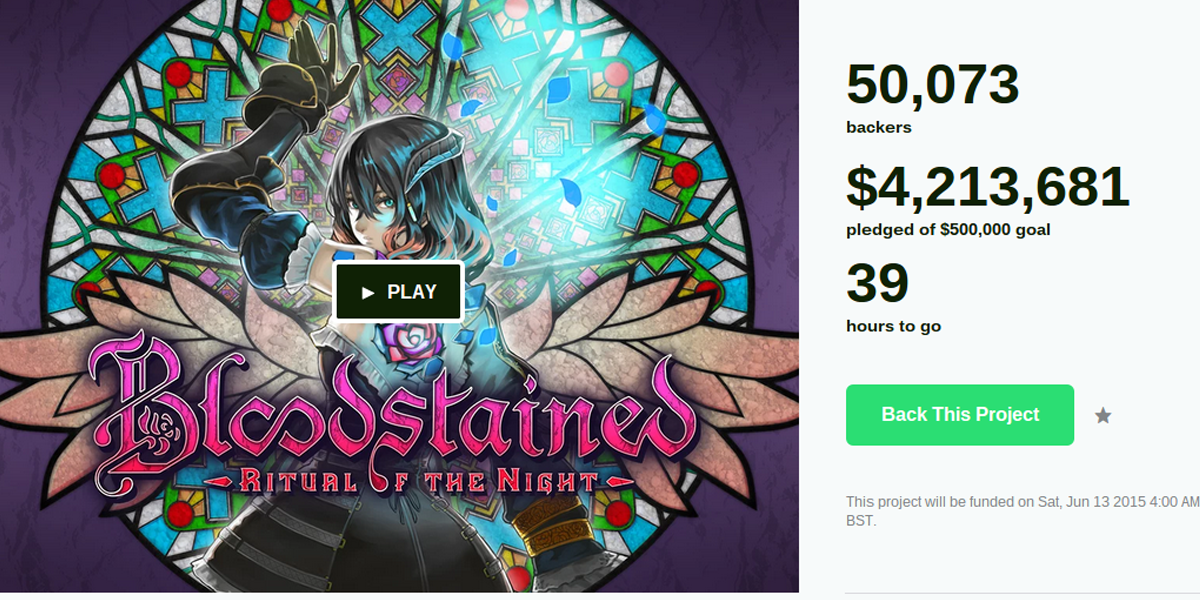

Crowdsourcing

I know this is a really touchy subject for some people: the system has become more of a marketing and preorder tool than a legit funding model. Other horror stories are out there about projects that have taken cash and either crumbled, or worse, disappeared altogether. The stigma gets worse considering that a lot of smaller campaigns are not successful, especially if they lack a big name or license.

But do you know what the alternative is? We go back to the old way of doing things. This was a system that saw indie developers diving head-first into an ocean of twits and charlatans that lurked the game industry and Silicon Valley and attempting to figure out which one was a legit investor. Even if they found such an investor, the developer likely got the extremely short end of the profit stick. And in most cases, that investor was likely a giant publisher, because honestly, they were almost the only game in town.

For all of crowdsourcing’s faults, it is by far the lesser of the two evils. And as lopsided as the system is toward big names and licenses, an indie outfit always has the chance that it can get their cool idea funded without going the old big publisher route.

Access to powerful game development tools

You’re still hanging out on my lawn? Well, young ‘un, do you know what else we didn’t have back in the day? Professional, powerful, and accessible game engines — for free.

For the cost of clicking a link and waiting 20 minutes for a file to download, I have a development environment capable of creating a commercial game on par with triple-A titles (as long as I have the execution chops to do that).

These tools are also becoming easier to use, allowing for quick prototyping and deployment to every modern gaming platform out there. A big reason for this is because the tools are automating a lot of otherwise complex and tedious stuff. It also helps that engines like Unity and Unreal Engine have a huge user community that is willing to help through forums and YouTube tutorials.

2015 is a game creator’s paradise compared to the ’90s, where the closest thing to these free engines was creating a total conversion mod in Quake.

We have a huge indie scene

Back in the days, I took over one of the earlier, if not earliest, independent game archives on the Internet (ftp.cdrom.com). The amount of content that was available from indie developers back then was extremely small. A lot of what was available to the public wound up being someone’s practice project, such as a clone of Tetris or Bust-A-Move.

What original games existed often featured unpolished gameplay and production. Nothing’s wrong with this, but the gap in overall quality between a game developed in the big publisher system and an indie title was usually huge compared to today. Part of this is because game development back then was damned hard, and if you were working as an independent, you weren’t privy to all the tips-‘n’-tricks of the trade. Hardly anyone shared information or tutorials to the outside world, let alone access to tools.

Some people are predicting the indiepocalypse. I shrug at the notion.

Because even if the indie scene becomes saturated, and the market sees a shake out, it’s still a much better situation than it was before. Creative people in the industry have tools and assets that give them an actual choice when it comes to what they want to work on.

In the former system, the game development path exclusively lead to one place: being chained to a publisher’s cubicle. If you were lucky, it was for a project you enjoyed, but a lot of horror stories from the era suggest it wasn’t the norm.

Competent real-time graphics for virtual reality

During virtual reality’s first big wave in the early ’90s, the selling point was a crazy vision of interacting within digital worlds that were beyond our imagination.

The problem is that what we got was something that, visually, fell incredibly short of that mark. It was hyperbole that technology wasn’t ready to handle for another decade, at least. Real-time rendering of polygons for interactive applications was still a huge high-tech hurdle.

Virtua Racing is a great example of where we were at the time, especially considering VR is a major buzz word behind the game’s name. Virtua Racing was originally a prototype of Yu Suzuki and Sega AM2‘s research into the possibility of using real-time polygons in game development. It wound up being so successful during in-house testing that Sega released it as an arcade game. It wasn’t the first game to render an entire interactive world in polygons, but it was considered a huge leap forward at the time, which should put things into perspective. It’s a great experience for its time (and I still like playing it), but it was nothing like what was being promised.

The virtual reality concept needed graphic technology and game art creation techniques to catch up, before we could see the idea become viable again. Speaking of which …

Virtual reality is ready to be legit

Now that graphics have finally caught up, virtual reality is in the middle of a serious relaunch. Especially with a product like the Samsung Gear VR available for purchase. The more cynical among us are claiming this is a fad, but in my opinion, this is just the growing pains of a new medium. We should be excited to be witnessing virtual reality’s rebirth.

This is like being an audience member for one of the first moving pictures, or playing one of the first video games. The fact that parts of this medium are clunky and need to be figured out is the exciting part.

Someone has to smooth those edges out, figure out the technical hurdles, design a solution to the interactive issue, and experiment with the new artistic language of virtual reality.

Who is going to solve this stuff, and how? I am envious, not critical, of those that get the opportunity to work on this stuff now. It’s an incredible time to be alive and interested in artistic creativity and interactive design.

That you and I are in a position to care about any of this

We get all wrapped up in discussing what project the hottest designers are working on, or the scandal that some publisher is wrapped up in, or get angry that an artist didn’t address an issue the way we wanted, or why this interactive experience is better or worse than another … but in the grand scheme of life, it’s all bullshit.

What matters are the basics. Food, shelter, security, family, love, and to be loved. It’s extremely difficult to possess all of those things at once, but for a great many human beings on this planet tonight, just holding onto one of these basics is a luxury.

It’s a blessing that I get to spend a significant amount of my day worried about games and tech, and that there are those of you reading this that are in the same boat. That’s a sign that you and I are doing pretty OK, overall, and let’s all be thankful for that.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More