Independent development is a scary thing. You don’t have the financial cushion of a large company to fall back on. Sometimes, you don’t even know when your game is coming out, and, assuming if anyone buys it, you’re not getting paid until it does. Yet despite all the uncertainty, many people still choose to go indie full-time … so I decided to find out why.

Back in May, a few local developers showed off their work-in-progress games at the first Indie Press Day in San Francisco. Held during a rainy evening, Indie Press Day organized 16 indies and as many plastic tables into a narrow row at a small coworking space. Nothing flashy or distracting was there, just the games and their very approachable developers. While each title on display had its own charm and ingenuity, what impressed me the most was just how many of the folks there used to work at large, well-known companies before taking the indie-game plunge.

The individuals I spoke with all had their own reasons for leaving their day jobs, but one common thread among them is that they all left voluntarily, an interesting (and fortunate) circumstance given the amount of layoffs that hit the industry seemingly every week. I also asked them a bit about their upcoming games, any unexpected challenges they’re facing from switching to indie development, and what they think about the thriving sector of indie games and the people behind them.

(Continued below. See part two here.)

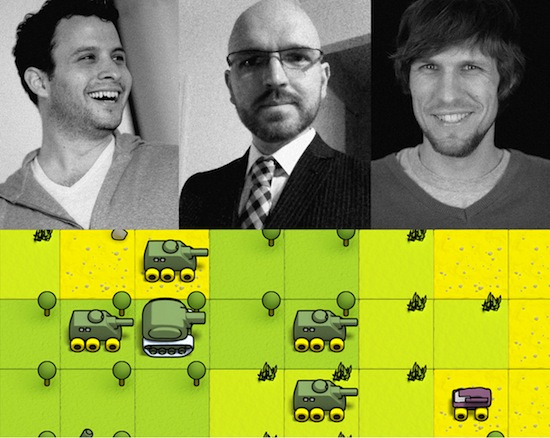

Ethan Levy, Quarter Spiral

Why he left

In his decade-long career in the games industry at companies like Pandemic Studios and Electronic Arts, Ethan Levy has occupied a variety of roles: intern, lead tester, programmer, game designer, producer, and consultant. But the most direct influence for Quarter Spiral came from Levy’s time at BioWare Social where he worked on the browser-based games Dragon Age Legends, Dragon Age Journeys, and Dragon Age Legends: Remix 01.

“What appealed to me about [BioWare Social] was that it was very entrepreneurial,” Levy said. “It was sort of like being in a startup within EA. I had a lot of room for growth and to try new things — to do experimental things. That’s how I met Alex [Kohlhofer], one of my two co-founders at Quarter Spiral.”

After key members of the team left BioWare to co-found their own startups — leaving Levy, Kohlhofer, and another employee in charge — Levy began to lose interest.

“Over the course of six to nine months, I started to feel a lot less like I was an entrepreneur,” Levy said. “I started to feel a lot more like I worked at the EA that people imagine EA is like. It just felt like it was time for a change, I guess. I wanted the freedom and exhilaration and all the challenges that were part of the early days of BioWare Social and not to feel like I was endlessly going to meetings and politicking and managing. … I just wanted to feel like I was making games again.”

Both Kohlhofer and Levy left BioWare around the same time. Shortly after that, they picked up Thorben Schröder as a back-end developer and formed Quarter Spiral.

Quarter Spiral’s first game: Enhanced Wars

Enhanced Wars owes a lot to Nintendo’s Advanced Wars, a series of handheld games that focuses on turn-based tactical combat. But instead of trying to develop a robust single-player campaign in the vein of Advance Wars, Levy says they want to deliver a “a multiplayer focused, turn-based strategy game that really overcomes some of the design foibles of your Advance Wars-style games.”

“A lot of turn-based strategy games and even real-time strategy games — if you have the reflexes to play them, which I don’t — are about kind of getting a small resource advantage over your opponent and then overwhelming them slowly with forces,” Levy said. “It’s really fun for both players for a short build-up phase. But then relatively quickly, one player gains an advantage that can’t be overcome. And then there’s kind of a long, boring mop-up phase.”

In order to avoid that last part, Quarter Spiral plans to design Enhanced Wars for “fast and aggressive” battles with a lot of “emotional volatility” for players. But it’s still far from being complete — the version shown at Indie Press Day was only a month old. Later this fall, the company will launch a crowdfunding campaign for Enhanced Wars on Kickstarter. For now, the target platforms are PC, Mac, and Linux.

Unexpected challenges

“I don’t know if I’ll be able to pay my rent [laughs],” Levy said. “At EA, your project might get canceled, but you’d still get your paycheck. Whereas here, there’s a very real possibility that our company will go bankrupt and then we’ll have to get real jobs. Dealing with that level of uncertainty is really hard.

“Just to give you some perspective on where my life is: I just got engaged. My fiancé and I are thinking of moving to North Carolina, but she wants to stay out here for work, and trying to do long-term planning is impossible for us right now because I literally have no idea whether three months from now [or] six months from now I’ll be at GDC [editor’s note: Game Developer’s Conference] trying to hunt down that next job. Or whether Quarter Spiral will be self-supporting, and we’ll be able to move to North Carolina whenever we want to.”

On the rise of indie developers

“I think indie games will play a bigger role in the next generation of consoles,” Levy said. “And the reason I think that is almost purely market dynamics. Like when a huge investment in Tomb Raider and millions of sales are only barely making a profit, the business models of those large publishers are — it’s really tough for them to make a profit with these giant teams and these giant games. That leads to studio closures and layoffs. Studio closures and layoffs don’t turn into people joining as many new studios as it used to. It turns to people founding their own studios … .

“I think that [for] a lot of people who are either choosing to leave corporate game development, like I did, or being forced to leave, going indie is a huge draw. Just look at how much money the guys making The Banner Saga raised with beautiful art, great team pedigree, and great vision. And now they’re developing the game they want to make instead of sitting in meetings or being handed design documents about the game they have to make.”

Pete Angstadt, Turtle Sandbox

Why he left

Pete Angstadt became discouraged from game development after his last studio job at the Electronic Arts-owned Maxis. While he was there, he worked as a programmer on an expansion pack to Spore, a game where players create and raise their own alien lifeforms. Though the project was complete, it never saw the light of day.

“[I] was just like, ‘My time is not being used very well here,’” Angstadt said. “As a person who wants to make games, you also want to have people play the games. If you spend a year and a half on something and nobody ever plays it, it’s kind of stinky.”

After the cancellation, Angstadt wasn’t even sure he wanted to make games anymore. So he took up a job at Havok, the company behind the titular physics engine widely used by game developers.

“While I was doing that, I was also making games on the side and entering them into as many contests as possible,” he said. “And one of those contests was Activision’s first independent games competition back in 2011. I entered that and forgot about it. Then months and months later, they wrote back to me and said, ‘Hey, you won first prize and you get $175,000, no strings attached.’ So I was like, ‘Alright, it’s time to quit and try and make this game.”

Realizing that he needed some help with the art, he joined up with his old Maxis coworker Theresa Duringer to form Turtle Sandbox.

Turtle Sandbox’s first game: Cannon Brawl

Known as Dstroyd back when Angstadt first submitted his prototype for the competition, Cannon Brawl is a 2D action strategy game for the PC. Angstadt describes it as the “next evolution of the artillery genre” that follows in the footsteps of games like Worms and Gunbound. Battles take place in real-time as you build mines, cannons, and shields to protect and fund your base (the castles) while attacking the enemy’s compound.

Even in the early version I played, it’s a lot of fun. Matches are hectic, especially as your weapons destroy portions of the map, leaving you with precious little room to build more towers and buildings. Cannon Brawl will have a single-player campaign as well as multiplayer options (online and local) when it launches some time this summer for PC.

Unexpected challenges

“On one hand, when you’re at a big company and someone says, ‘Do this thing!’ You think, ‘Oh, that’s a terrible idea, why would I do that?’” Angstadt said. “But you have to do it anyway because it’s your job. And then at the end of the day, when maybe it didn’t work out, you kind of have like a way to protect your ego, like, ‘Oh I knew that was a bad decision. If I was in charge, I would have never done that.’

“And one of the scary parts of being indie is now I am in charge. And if my decisions are terrible, then it’s only me I have to blame.”

On the rise of indie developers

“I feel like the audience for games is getting a little bit tired of your standard triple-A game,” Angstadt said. “They also don’t want to pay $60 for another sports simulator or shooting simulator. Maybe they want to try five new interesting games for the same price. And at the same time, you have these triple-A companies with a lot of talent that they’re maybe not utilizing as well as they could. Those talented people are going to try and strike off on their own, basically.”

Ian Stocker, MagicalTimeBean

Why he left

For nearly a decade, Ian Stocker was a self-employed musician doing contract work for games: composing soundtracks, sound design, and audio direction for his clients. Aside from taking a few piano lessons, he doesn’t have any formal music training — he just started making music with computers when he was a teenager.

Though he contributed to a bunch of indie projects early on (none of which came out), one game in particular helped get his career off the ground. He made 30 songs for a Game Boy Color role-playing game called Mythri, which was close to being done before development fell apart. A programmer on that game went on to work for Amaze Entertainment, and he used Mythri (complete with Stocker’s music) as his portfolio. Amaze was looking for someone who specialized in handheld console development, so an executive producer reached out to Stocker, and that kicked off his contract work and the start of his one-man company, Ian Stocker Soundesign.

While he loved what he did, Stocker just couldn’t pass up the chance to make his own games when the opportunity arose in 2009.

“A couple of projects I was supposed to get started on actually got canceled,” he said. “So I had set aside several months to work on these, and suddenly I had a vacuum that I needed to fill. So I just went to the coffee shop and started to learn XNA and started a new game project. Five months later, I finished my first game and launched it on Xbox Live Indie Games. That was [the action RPG] Soulcaster.”

Now working under the name MagicalTimeBean, Stocker made two more games: Soulcaster 2 and Escape Goat (a puzzle platformer).

“I think I learned a lot doing the contracting thing,” Stocker said. “That’s part of why I set out to make my own games: I started to develop opinions on game production, watching a bunch of games being made from start to finish, seeing what stuff worked and what stuff didn’t work in my opinion. That kind of gave me a jumping off point for how to develop games on my own. So I definitely think it was a huge advantage for me to have witnessed these 30 or 40 game projects as an outsider and then go in and try my hand at it.”

MagicalTimeBean’s newest game: Escape Goat 2

Stocker’s decision to work on an Escape Goat sequel was partly due to the old-school appeal of the first Escape Goat, which looks like it came from the Nintendo Entertainment System era. Stocker brings up the game’s aesthetic as proof that maybe it was too old-fashioned for some players, as he still hasn’t been able to get it on Steam (Valve’s popular digital platform on PC) via the Greenlight community program. So instead, he set out to make Escape Goat 2.

“What if I took the same game concept, made a new game, had HD graphics for it, and try it again?” Stocker said. “Because Escape Goat had a really good critical and fan reception, and I felt like there was a little bit momentum I could spring off of from the first game, rather than let that die out over a year or something and try and resurrect it later.”

In Escape Goat 2, you have to solve a series of clever puzzle rooms (100 in all) by using the goat’s abilities and the powers of his magical rodent companion. Navigating the mechanical platforms, fire balls, and the other challenges the game throws at you takes some time getting used to, but you’ll feel that much smarter once you figure out Escape Goat 2’s internal logic.

It’s set for release on PC this summer.

Unexpected challenges

In addition to the abrupt change in the frequency and size of his paychecks — Stocker hopes to reach “a similar amount” to what he was making as a contractor in the next couple of years — he found it challenging to promote and market his games, something that he never had to do before.

“I didn’t realize how much work you need to put into promotion of your stuff,” Stocker said. “Like making a quality game is an important part of the equation, but it’s one of like five things. Just the amount of time spent on the website, Twitter, media stuff, interviews like this one — it all helps tremendously. I didn’t know that going in because I was used to just dealing with customers who came to me through word-of-mouth. I didn’t have to do a ton of sales-pitch-type stuff. So that was a huge learning curve.”

On the rise of indie developers

“That seems to be happening all the time — a lot of people are leaving their triple-A jobs either of their own volition or, in less fortunate cases, not — and starting their indie company or trying to get a new team,” Stocker said. “Because the cost to distribute is so low and there’s so many different ways to distribute your game now, you don’t necessarily need a publishing contract. You don’t need an expensive dev kit in some cases; even console [manufacturers] are willing to work with you a bit more.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More