Casey Carlin was ready to quit. He spent the last two years working on user interfaces for a Japanese developer, but he knew that if he stayed, he’d be stuck doing UI over and over. It was time for a change. So he packed his bags and moved back home, unsure of what he wanted to do next.

It took about a month and a half before Carlin came up with an answer. Inspired by the release of the critically acclaimed Braid and Super Meat Boy, he found that he could no longer resist “the siren song of indie development.” He gathered a few friends and they immediately began work on their first game.

His story isn’t unique. More and more people are leaving their day jobs to work as indie developers full-time. Some of them were present at the first Indie Press Day in San Francisco, where 16 developers showed off early versions of their games. In part one of the interview series, I talked to talented folks who previously worked at studios like BioWare and Maxis. This time around, we’ll travel across the Pacific to trace Carlin’s career, and then bounce back to the States to see how Kent Hudson went from designing blockbuster shooters to a beautifully subdued game about a struggling writer and his family.

Casey Carlin, Whole Hog Games

Why he left

Carlin began his career through a more unusual route: Japan. At first, he tried applying for a Japanese internship via a special co-op program at his college, the University of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif. But the school rejected his application, and he got the same answer when he applied for it the second time around. So Carlin decided to send out cold emails to as many Japanese developers as he could, saying he was “desperate” because he “really wanted to work in Japan” for his internship.

The emails paid off. Arc System Works (known for hardcore 2D fighting games like Guilty Gear and BlazBlue) was one of the few companies that responded.

“[It] had just recently started a push for being a little bit more … ‘global,’ I guess would be the right way to put it,” said Carlin. “They took my email as an opportunity to test the waters.”

He spent six months as an intern at Arc System Works in Japan, eventually transitioning to a full-time position after he graduated from college in 2009. During his time there, he worked on the user interface (UI) for games like Hard Corps: Uprising and would sometimes help out with translation duties as well.

“My friends and family were all really annoying and kept telling me to come home,” Carlin joked. “And that alone I think I could ignore, but part of it was — one thing that’s really easy to happen when you’re working at a big company is that it’s really easy to become ‘that guy’ for a particular field. And I was almost positive — I read the writing on the wall that I was going to get pigeonholed into working on UI for the entire time that I was at Arc System Works. That wasn’t bad necessarily. I definitely enjoyed what I was doing. But I don’t like getting stuck in a particular position.”

Once he realized that he was “never going to escape that” and that he could never aspire for “legitimate seniority” at Arc because his communication ability “would always keep [him] away from being able to do a good job,” he decided to leave the company after two years. But mother nature also contributed to his move back to the United States.

“The [2011] earthquake was definitely also a factor,” he said. “I already had my exit interview, and I think that the earthquake hastened my time table because the cries from my friends and family were significantly louder after that. They were convinced that Tokyo was next and that I had to get out of there. I’d like to say I could’ve ignored them, but their concern was so genuine that it kind of reminded me that I was really isolated there.”

By the time Carlin got back, he had “mostly” made up his mind to work on a new game with two friends, Finn Beazlie (an illustrator) and Jake Federico (a programmer). Together, they founded Whole Hog Games.

[youtube http://youtu.be/EXhOyTD6Tik]Whole Hog’s first game: Full Bore

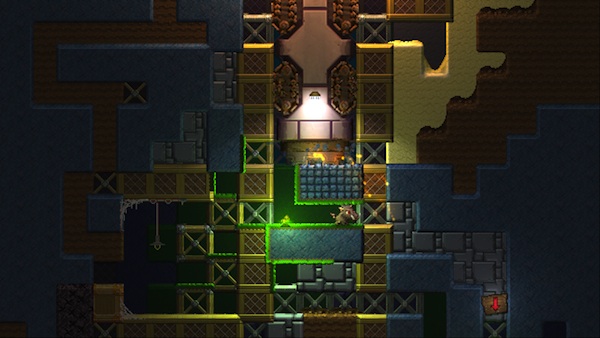

Whole Hog’s first project stars — as a nod to its name — a boar. In the press demo, the boar (named Fredrick) woke up in an idyllic pasture before stumbling into the gritty world of vast, underground mines where other boars work. He quickly finds himself working with them, and from there, Full Bore opens up. Similar to games like Super Metroid, you can explore the levels at your leisure to find secrets or to piece together fragments of the story. Some areas are inaccessible until you learn a specific ability; Fredrick can already do everything, but it’s up to you to find out what those abilities are.

It was Super Metroid’s innovative visual language that led Whole Hog to adopt this approach.

“That’s undeniably a thing about Full Bore that we focused on because of how well that works in Super Metroid: just trusting that the player will be able to put stuff together if you give them the opportunity to,” Carlin said. “That’s why just about everything important about the puzzles is taught visually. You’re forced into doing something once or a few times. You’ve got to be paying attention when that happens. But if you do, then it opens up all kinds of doors all over the game.”

I must have spent close to a half-hour just wandering around the demo, finding things Carlin talked about as well as a few secrets, like a hidden area with portals that transported me to specific locations (kind of like a fast-travel system). Full Bore embraces the magical realism genre with its blue-collar atmosphere, talking animals, and little hints of the supernatural. It’s a world that wouldn’t look out-of-place in a Pixar or Disney film. Even Fredrick’s animations — particularly the way his head melts into the ground when you slam it — are charming. Carlin cited a Penny Arcade post by Mike Krahulik as a source of inspiration for these “stupid ideas.”

The team is aiming for a late summer release for Full Bore on PC and Linux, with a possible Mac version to follow if they make enough money to buy a Mac.

“That’s the bummer about being an indie dev: can’t afford that $2,000 computer,” Carlin added. “Gotta eat first [laughs].”

Unexpected challenges

“I am devastatingly poor,” Carlin said with a laugh. “I haven’t worked on anything other than Full Bore for the past year. And the savings I brought back from Japan are gone. And the Kickstarter money is pretty much out as well. That’s actually one of the things that’s been rough: not working for The Man means that it’s really hard to keep a schedule. Fez took five years. I don’t want to take five years.”

He also noted the challenges that arise with working in a small team since both Finn and Jake have other jobs and family obligations to take care of first.

“Having multiple people working on the game kind of hurts our ability to go fast because I’m the only person who works full-time,” he said. “Finn is taking care of his two toddlers, so he’s part-time stay at home dad, part-time artist. And Jake is still working full-time as an engineer. He’s basically able to be the company sugar daddy. He pays the rent for his house so that we can use one of his rooms as the office and stuff like that.

“With a game that’s only being worked on by three people, it has to have something from all of us in it. So I can’t just forge ahead and work on stuff without Finn and Jake being involved because then I think the game would just become ‘my’ game or it would become dishonest. They certainly kept me from being lonely, but at the same time, it’s also kept us from being a bit fast. I don’t think I’d have it any other way, though. It’s interesting and new for me to have to deal with making sure that everybody is contributing to the game. I think that heart is something that’s hard to quantify but so important to a game [like this].”

On the rise of indie developers

“I do think you’re gonna see people leaving the industry and going on and making their own stuff,” Carlin said. “And I don’t think it’s just gonna be the people who’ve been really successful and who have gone on to run their own studio because they want to do things their own way, which has certainly happened. I don’t think that there’s much room in the middle in the games industry anymore. So you will see a lot of indie stuff like that.

“I think that’s actually going to happen maybe in Japan — and maybe sooner because their games industry is in a really bad place. The only companies that seem to be doing well for themselves right now [over there] are companies that are about the size of Arc System Works: agile enough to pivot and keep themselves profitable but also small enough to be willing to try new things.”