Times are changing for traditional game publishers. As crowdfunding becomes the norm rather than the exception, they’re in danger of becoming irrelevant to a growing army of self-driven developers.

But a change of management at Square Enix, the publisher behind the hugely successful Final Fantasy role-playing series and Tomb Raider action-adventure games, brought a change in thinking. New Square Enix president Yosuke Matsuda expressed a desire to reconnect with the gaming community and build relationships with fledgling development teams — partly as a way to seek out new intellectual properties.

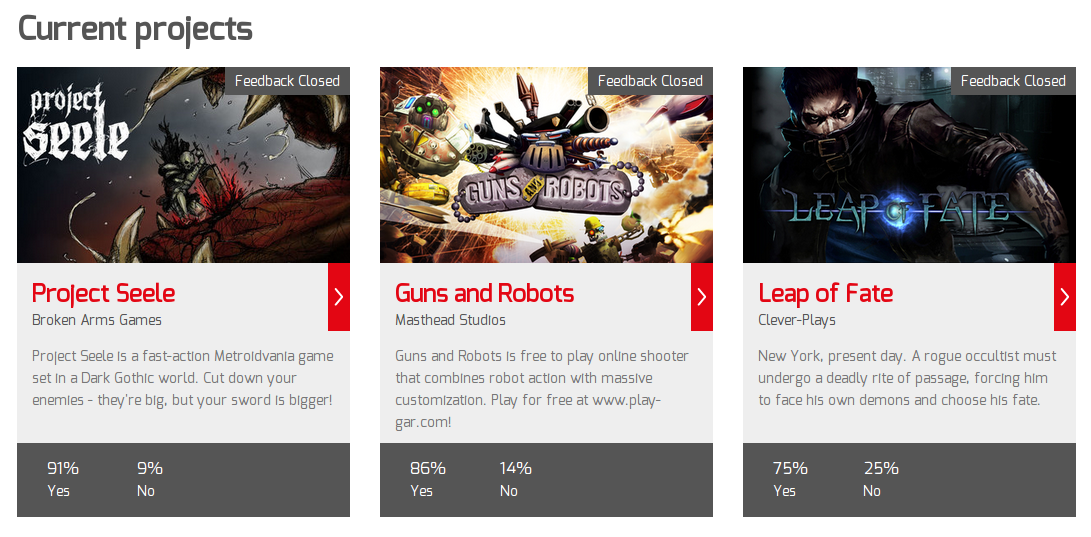

Phil Elliott, the head of community at Square Enix Europe, ran with those ideas and came up with the Square Enix Collective. It’s a platform for developers to get feedback on their game ideas and build awareness before heading into the hazardous waters of crowdfunding initiatives like Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

But with no obligation for the developers to distribute or publish with Square Enix if they get funded, there must surely be a catch. Big publishers don’t let games (or money) slip through their fingers, right? GamesBeat spoke to Elliott to find out more.

The word from the top

Square Enix announced the Collective project last October and launched it fully in April of this year. But two weeks before the initial announcement, the terms for potential developers were still unclear.

Elliott wanted the project to be open, but he was sure that senior management would want to tie developers in to a distribution and publishing deal once they’d signed up.

“The structure was [originally] built on the idea that once you submit to the feedback platform and you go live, then if we offer to help you through funding, then you have to accept,” said Elliott. “If we offer to distribute, you have to accept. I thought they’d never go for it otherwise.”

Matsuda had other ideas, though. In a conference call to Tokyo with Matsuda and “a few higher-ups,” Elliott explained the Collective structure to him.

Matsuda sat and thought before saying “no,” according Elliott, who described the president’s reaction: “[He said] the mantra for this project is the developer chooses. We do not force people to work with us. After feedback, there are no ties; after funding, there are no ties.”

“I thought, ‘this is great,’” said Elliott. “‘I’ll happily go out and tell people this message.’ [Matsuda] understands where the lines are and what we want to achieve.”

The Collective goals

The Collective has posted pitches on more than 40 projects from around 16 countries now. Two have made it through the process and gone into a crowdfunding phase. One, Moon Hunters, just raised $160,000 on Kickstarter, much to Elliott’s delight.

But how does the process work, and what’s in it for Square Enix?

“There are selfish reasons, and there are broader reasons that make sense for the industry,” said Elliott. “We do want to find new teams to work with. We do want to find new talent and potentially new IP to invest in.”

But there’s no time frame for this, and developers have no obligation to accept any offer of direct investment. In the meantime, Square Enix will help support independent teams through the Collective, hoping to make connections and engage the community along the way.

There’s no charge for developers to sign up to the Collective, which gives them 28 days to build an audience and get feedback from the Square Enix community. “We look at the feedback phase as kind of a practice run for when they do go on to crowdfunding,” said Elliott. “We want to help them learn as much as possible in that time.”

Square Enix then offers its support through crowdfunding to successful projects — after digging down to assess whether the dev team will actually deliver — in exchange for 5 percent of the money they raise. “That’s not because we think we’re going to get rich from 5 percent of small crowdfunding campaigns,” said Elliott. “That’s really just so we can cover the costs of creating the platform.”

Teams that successfully complete funding get an offer from Square Enix to help with distribution, but, again, this is obligation-free.

“If we do distribute, then it’s a very defined process,” said Elliott. “In return for QA support, getting the game on Steam, and then handling all the sales process, we ask for 10 percent of net revenue, which is equivalent to about 6 percent gross. It’s a pretty skinny cut.”