Building a community

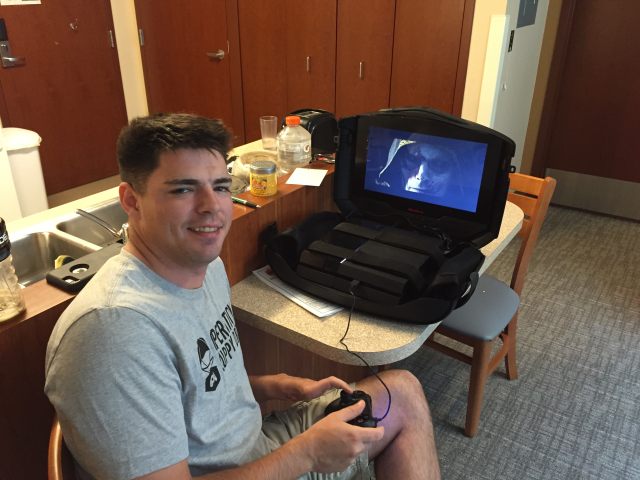

OSD’s Teams program brings together veterans, active troops, and civilians for a chance to game, go to the movies, play team sports, or just hang out. But most important, it provides a chance for veterans to get together to talk and hopefully help each other out. Teams’ broad focus is deliberate to ensure that vets aren’t just playing video games in their home but are also going out and making important social connections.

“I love video games, but it gets very easy to lock yourself in your door and do what I was doing, with twelve hours of video games and not eating, sleeping, or showering,” said Machuga, referring to the World of Warcraft addiction he managed to break after getting a speeding ticket while rushing back home to join in a raid. “That’s not exactly completely healthy. We want to make sure that guys are getting out there, seeing one another, shaking hands.

“We’re making sure that vets are able to talk with one another so they don’t feel alone,” said Machuga. “[So] they’re not isolated.”

Machuga’s hoping that his Teams groups — which number 50 across six countries — will grow into robust communities that can offer support to those people who are finding civilian life toughest. It’s the one part of Operations Supply Drop that he thinks will be most important in the future.

“Between homelessness and joblessness, guys [are] getting out of the military and [are] just thrown to the wolves, more or less,” he said. “[It’s] thank you for your service, a pat on the back, and see you later. Guys are not set up.

“I was lucky. I had a degree and I had a security clearance. Otherwise, I have no idea what I would be doing now. Seriously.”

The military does try to help, says Machuga, but it doesn’t do a lot beyond assisting outgoing troops write a resume and giving them some basic interview techniques.

“There’s a reason there’s a three-month waiting list to get into a VA hospital for a basic check-up,” said Machuga. “Money is going forward to buy bombs and bullets. It’s not getting put into supporting troops when they get out.

“It’s a lot easier to buy a Tomahawk or cruise missile than it is to medically retire someone and pay them a decent wage so they don’t have to go and flip burgers at Denny’s and be disabled.”

An example of success

Sgt. Steven Giddings is one of Operation Supply Drop’s big success stories.

Giddings took a sniper round in the neck while on active duty in Iraq. He stayed there for two more years before he was finally sent home, where he found he just couldn’t cope with civilian life.

Despite being in a very dark place, Giddings managed to enrol himself on a game development course at Austin Community College some months after returning home. “After months and months of playing video games and PTSD appointments after returning, something just told me to do it,” he told me via email.

It was from there that he found Operation Supply Drop, and he hasn’t looked back since.

“Operation Supply Drop has saved my life in so many ways,” said Giddings. “I was on a path downhill where I didn’t want to talk to anybody; I was scared of the world, and all I wanted to do was end my life. I was in a place in my life where I hated the world and everything that happened to me.”

Operation Supply Drop sent Giddings out a supply drop that contained an Xbox One and a bunch of games, including Battlefield 4, Titanfall and Call of Duty. They sound like titles that wouldn’t help a soldier struggling with PTSD, but they were exactly what he says he needed.

“I was an infantry man,” said Giddings, “and this is what I did for a living.” He says that playing games like Battlefield 4 puts him in a “happy place” where he thinks of the good times (and hard times) he had in the army and forgets the day-to-day pain that he experiences. “These games helped with missing the military so much that all I had to do was play for a little and I felt better,” he said.

And the charity has continued to support Giddings in putting his life back on track, beyond that initial supply drop.

“They took me under their wing and guided me into the life I have today,” he said. “OSD gave me the brother- and sisterhood that I thought I lost when I got retired out of the army. If it wasn’t for OSD and [chief executive officer] Glenn Banton, I’m not too sure what direction my life would of gone, but I’m glad it’s now in its true direction.”

Giddings qualifies from Austin Community College this August, and he’s currently making a game in Unreal Engine 4 called Angels over Darkness. He reckons he wouldn’t have made it this far with the support of OSD. “[They] made it very easy for me to stay and continue school even when I thought I couldn’t because I did struggle a lot,” he said. “My PTSD, TBI [traumatic brain injury], chronic pain and brachial plexus nerve damage made things really tough.”

Machuga is clearly proud of how OSD has helped Giddings, and it’s a model of what he’s hoping to do with the Teams program going forward.

“When we got a hold of [Giddings], he couldn’t go out in public,” said Machuga. “He was a wreck of a man, and now he’s out there smiling and shaking hands with guys and being sociable again, and it’s because of video gaming. He really had problems doing anything, and now he’s part of our events coordination team. He’s been to PAX [Penny Arcade Expo] and helped set up booths.

“That’s the kind of stuff we’re trying to push with our Teams program,” said Machuga. “Just getting guys out there, getting them involved and active and doing something that takes their mind off what they’re fearful about, so to speak — what they’ve got going on in their heads.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More