When Capt. Stephen Machuga left the U.S. Army, he had a hard time readjusting to civilian life. Trash day, in particular, was hell.

“There’s trash everywhere in Iraq,” Machuga told me over a Skype chat last week. “On the sides of the roads, piles and piles of trash everywhere. It’s a popular place for insurgents to bury wired IEDs [improvised explosive devices].” So whenever Machuga saw trash at the side of the street back home, an alarm in his brain would go nuts, telling him to watch out. He knew it was irrational, but this awareness didn’t help.

It took a video game to help Machuga cope with being back in the United States. Just three weeks after he left the army, World of Warcraft released, and Machuga dived deep — a little too deep, it later turned out — into its multiplayer fantasy world.

Ten years on, and Machuga’s now using the power of video games to help soldiers and war veterans. His charity, Operation Supply Drop, sends gaming packages to troops on the front lines, those recovering in military hospitals, and the guys who the military machine has spat back into a world that has moved on without them.

And with 22 United States veterans committing suicide every day, Operation Supply Drop’s work with vets — helping them to cope with civilian life and form self-supporting communities — is quickly becoming its most important role.

The first supply drop

Machuga was always into video games. “Whether I’ve been working in McDonald’s or sitting in the middle of Baghdad on my birthday … whenever I’d get done, gaming would be there.”

He took his Nintendo DS with him to Iraq and played it during the lengthy downtime that active troops have every evening — time when there’s often not much more than an old Ping-Pong table around to distract you from reality.

Machuga’s first gaming supply drop was actually for himself. He nearly died in a mortar strike, and the next day, he jumped online and ordered a beast of a gaming laptop. “Might as well, you know,” he said. “Gotta live for the moment.

“That just changed my experience over there. The last six months of my tour went really quickly after that.”

A whole lot of DJ Hero

A few years back into civilian life — and after a lot of time “floundering” — Machuga heard from his old driver, Jeff, who’d been posted to Afghanistan. Jeff knew that Machuga had started writing for a website called Sarcastic Gamer, the site that went on to spawn the gaming charity Extra Life.

“He reached out and said, ‘Hey, do you think you can get my guys and I some video games; we’ve nothing to do over here.’”

Machuga flicked through his Rolodex and reached out to see if any gaming companies would help. He got a response from Dan Amrich, then the community manager at Activision, who sent him out a ton of Guitar Hero and DJ Hero kits.

Machuga managed to ship some of these to Afghanistan, and they were a huge hit. “Jeff sent back pictures of them having DJ Hero competitions using a briefing projector on the side of a trailer,” said Machuga.

It made him realize that game companies do have stuff lying around that they’re happy to give to the troops, and Operation Supply Drop was born.

“Dan’s initial donation definitely gave me the courage to ask other developers and publishers,” said Machuga. “It took a little bit of movement. I didn’t always hear back, but there were definitely developers who came forward and went, “We love this, we want to get involved, we want to help the troops.’”

The donation that started it all

I reached out to Dan Amrich, now the community developer at Ubisoft, and asked why he’d responded so generously to Machuga’s initial request all those years ago.

“When Stephen approached me, it was with a very personal, direct introduction,” said Amrich. “When he told me what he was trying to achieve, I simply put myself in the position of the soldiers on the frontlines. It’s something I can’t imagine going through. I’ve never served in the military; my grandfather served in World War I, and I never met him. I get upset being away from my wife for a weekend, so the reality of being miles from everything and everyone familiar for years is something I can barely fathom.

“Hearing that the games would go directly to the troops stationed in hot zones made a big impression on me. Giving people an experience fundamentally meant more to me than just donating a raffle prize. I hoped having a Guitar Hero night might give them a little of that comfort of home and a little distraction from their reality. If I were in their place, I would truly miss the simple escapism of playing games after a hard day at work — and I couldn’t imagine a harder day at work than being in a combat zone.”

Amrich pointed out that Maryanne Lataif, Activision’s senior vice president of corporate communications for nearly 20 years — and Amrich’s boss at the time — was immediately on board with the idea as well. “It was one of those one-minute conversations,” he said. “Like, ‘Hey, there’s this charity,’ and by the time I relayed the basics, she said ‘Absolutely.’”

The photos of the gear in action — including the briefing projector gaming session — just cemented the relationship between Activision and OSD.

“I don’t think I deserve as much credit as Stephen often offers me,” said Amrich. “But I’m honored to have helped. He’s doing the work — I was just the guy with a few extra plastic guitars.”

The need for help

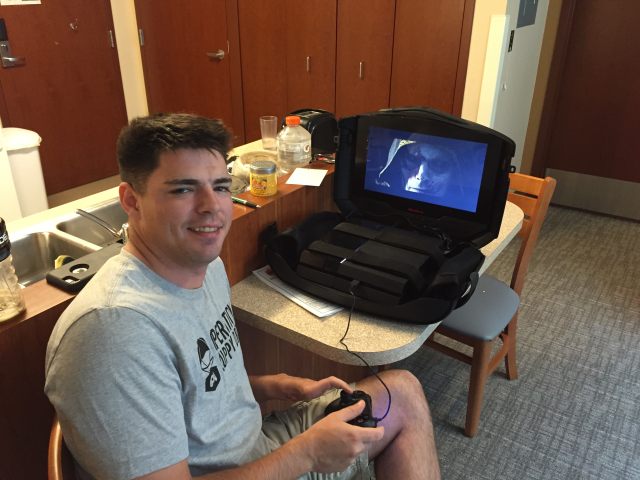

Fast forward to 2015, and Operation Supply Drop has grown way beyond Machuga’s basement. It gets support from charity game streamers on sites like Twitch and has a bunch of partner companies that regularly contribute gaming gear. The standard supply drop package now includes a Gaems portable screen — tough enough to play out of the back of a Humvee — with a PlayStation 4 or Xbox One, a couple of controllers, a gaming headset, and a bunch of games.

I asked Machuga if the active troops he’s sending these drops to could get hold of this stuff themselves, and he explained a bit about the economy of being on the frontline.

“Your enlisted guys, as much as combat pay and tax exemption works in their favor, they’re not making a whole mess of money. Us sending like $3,000 or $4,000 worth of gear to them, that is a deployment-changing event, not just for one dude but an entire platoon or company.

“They can do it on their own, but Private Snuffy should not be spending that kind of money on stuff like that. He should be putting it away or figuring out the future.”

And the troops who’ve already made it home need Machuga’s help even more.

Every day, 22 U.S. war veterans commit suicide. Researchers say that the experiences that troops live through while on duty and when coming home are what heighten their risk of suicide.

“I was in light combat at best, and I still had problems,” said Machuga. “The guys who are kicking doors and pulling triggers every single day for 360 days … I can’t even imagine what it’s like coming from that environment. It is definitely a problem.”

Looking for a comparison, Machuga likened active service with going to prison.

“You are just locked away from the rest of the world,” he said. “The world moves on without you, and when you get out you have this series of experiences — possibly violent experiences — that you can’t really describe to anyone other than someone who has been in prison. Everybody else is just going to Starbucks and living their lives. You get released into that.

“It just hurts your brain,” said Machuga, struggling to put the depth of the experience into words.

Games that Operation Supply Drop provides give veterans something to focus on other than their memories of war and their difficulties readjusting to the everyday. And Machuga is now using OSD to bring young veterans together in a social program called Teams — an alternative to the Veterans of Foreign Wars for a generation that relates more to Halo than to bingo.

Building a community

OSD’s Teams program brings together veterans, active troops, and civilians for a chance to game, go to the movies, play team sports, or just hang out. But most important, it provides a chance for veterans to get together to talk and hopefully help each other out. Teams’ broad focus is deliberate to ensure that vets aren’t just playing video games in their home but are also going out and making important social connections.

“I love video games, but it gets very easy to lock yourself in your door and do what I was doing, with twelve hours of video games and not eating, sleeping, or showering,” said Machuga, referring to the World of Warcraft addiction he managed to break after getting a speeding ticket while rushing back home to join in a raid. “That’s not exactly completely healthy. We want to make sure that guys are getting out there, seeing one another, shaking hands.

“We’re making sure that vets are able to talk with one another so they don’t feel alone,” said Machuga. “[So] they’re not isolated.”

Machuga’s hoping that his Teams groups — which number 50 across six countries — will grow into robust communities that can offer support to those people who are finding civilian life toughest. It’s the one part of Operations Supply Drop that he thinks will be most important in the future.

“Between homelessness and joblessness, guys [are] getting out of the military and [are] just thrown to the wolves, more or less,” he said. “[It’s] thank you for your service, a pat on the back, and see you later. Guys are not set up.

“I was lucky. I had a degree and I had a security clearance. Otherwise, I have no idea what I would be doing now. Seriously.”

The military does try to help, says Machuga, but it doesn’t do a lot beyond assisting outgoing troops write a resume and giving them some basic interview techniques.

“There’s a reason there’s a three-month waiting list to get into a VA hospital for a basic check-up,” said Machuga. “Money is going forward to buy bombs and bullets. It’s not getting put into supporting troops when they get out.

“It’s a lot easier to buy a Tomahawk or cruise missile than it is to medically retire someone and pay them a decent wage so they don’t have to go and flip burgers at Denny’s and be disabled.”

An example of success

Sgt. Steven Giddings is one of Operation Supply Drop’s big success stories.

Giddings took a sniper round in the neck while on active duty in Iraq. He stayed there for two more years before he was finally sent home, where he found he just couldn’t cope with civilian life.

Despite being in a very dark place, Giddings managed to enrol himself on a game development course at Austin Community College some months after returning home. “After months and months of playing video games and PTSD appointments after returning, something just told me to do it,” he told me via email.

It was from there that he found Operation Supply Drop, and he hasn’t looked back since.

“Operation Supply Drop has saved my life in so many ways,” said Giddings. “I was on a path downhill where I didn’t want to talk to anybody; I was scared of the world, and all I wanted to do was end my life. I was in a place in my life where I hated the world and everything that happened to me.”

Operation Supply Drop sent Giddings out a supply drop that contained an Xbox One and a bunch of games, including Battlefield 4, Titanfall and Call of Duty. They sound like titles that wouldn’t help a soldier struggling with PTSD, but they were exactly what he says he needed.

“I was an infantry man,” said Giddings, “and this is what I did for a living.” He says that playing games like Battlefield 4 puts him in a “happy place” where he thinks of the good times (and hard times) he had in the army and forgets the day-to-day pain that he experiences. “These games helped with missing the military so much that all I had to do was play for a little and I felt better,” he said.

And the charity has continued to support Giddings in putting his life back on track, beyond that initial supply drop.

“They took me under their wing and guided me into the life I have today,” he said. “OSD gave me the brother- and sisterhood that I thought I lost when I got retired out of the army. If it wasn’t for OSD and [chief executive officer] Glenn Banton, I’m not too sure what direction my life would of gone, but I’m glad it’s now in its true direction.”

Giddings qualifies from Austin Community College this August, and he’s currently making a game in Unreal Engine 4 called Angels over Darkness. He reckons he wouldn’t have made it this far with the support of OSD. “[They] made it very easy for me to stay and continue school even when I thought I couldn’t because I did struggle a lot,” he said. “My PTSD, TBI [traumatic brain injury], chronic pain and brachial plexus nerve damage made things really tough.”

Machuga is clearly proud of how OSD has helped Giddings, and it’s a model of what he’s hoping to do with the Teams program going forward.

“When we got a hold of [Giddings], he couldn’t go out in public,” said Machuga. “He was a wreck of a man, and now he’s out there smiling and shaking hands with guys and being sociable again, and it’s because of video gaming. He really had problems doing anything, and now he’s part of our events coordination team. He’s been to PAX [Penny Arcade Expo] and helped set up booths.

“That’s the kind of stuff we’re trying to push with our Teams program,” said Machuga. “Just getting guys out there, getting them involved and active and doing something that takes their mind off what they’re fearful about, so to speak — what they’ve got going on in their heads.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More