When morality systems started becoming more prevalent in games, it sounded like one of the best ideas ever. It became one of those no-brainer, innovative steps that would evolve titles into deep, thought-provoking experiences that might possibly force Roger Ebert to get on his knees and apologize for underestimating the awesome emotive power of the medium.

Ironically, that seems to be the exact opposite of what we see today. The last couple of years brought some very important titles that brandished their morality-based gameplay at the forefront, and most of them couldn't be more artificial in that regard.

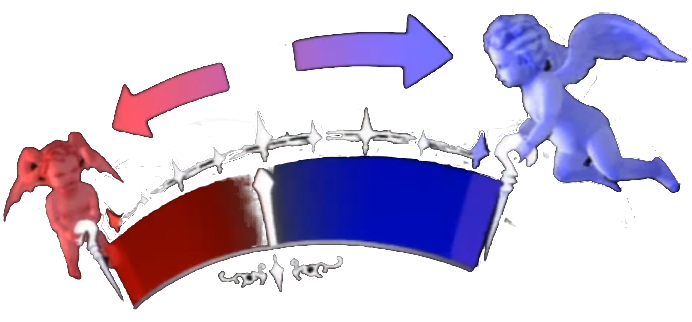

What do Infamous 2, Mass Effect 2, and Catherine have in common? They each use points and meters to determine whether the player has been good or bad. For that same reason, they all punish players who favor middling, natural response patterns. How often do normal people wake up in the morning and think "I'm going to be completely awesome to everyone today," or "I'm going to make it my mission to punch every last person I interact with in the balls." According to developers like Sucker Punch, quite a lot.

In the Infamous franchise, moral choices determine what powers the player gets, and the consistency of those choices determines how powerful they become. If the player doesn't stick to either exclusively good or exclusively evil responses, they'll make it to the end of the game without any high level abilities. This isn't any fun at all, especially since the difficulty of the game is pretty unforgiving.

In Mass Effect and Mass Effect 2, teetering between the Paragon (good) and Renegade (bad) responses meant, very soon, the player would encounter a choice requiring a high level of one or the other. Because they didn't commit to one extreme, the game will also limit all future decisions. Choosing a "neutral" reply (usually in the middle between the Paragon and Renegade options) doesn't do much of anything in terms of getting stuff done or expanding the situation. In fact, they seem more like punishments for players who didn't build points fast and consistently enough to choose one of the two moral-based responses, which is extremely frustrating.

Catherine rests the entire plot on the foundation of its awkward meter that rates random personality tests and in-game dialogue options as Law (good) and Chaos (bad), which made that game incredibly frustrating to play. Not only will playing the middle-ground give one of the most depressing endings, but the entire moral choice mechanic is layered on top of the main character Vincent's scripted personality. The player may want to be as evil and chaotic as possible, but during most of the cut-scenes, Vincent is going to try his damnedest to be the good guy and pursue Katherine (the Law choice) until the end-game. Then the system tallies the morality points and serves up one of eight tacked-on ending scenes.

But wait! Those who crave a more genuine experience can find some saviors. CD Projekt RED's action role-playing game, The Witcher 2, introduces morality gameplay by not having a system at all. Gamers won't find any meters or points or any intrusive indicators to teach them right and wrong. They understand that, as human beings, we already know these things.

The brilliance of The Witcher 2's take on moral choices shines in character interaction. Whatever the player does to an NPC in the game, that NPC will remember and react to it. Scorn someone early in the game, and they'll likely respond in kind. Likewise, lend someone aid, and they might make life easier someday. This lends to a cycle of great characterization giving power to actual player choice, which, in turn, further expands characterization. It's a refreshing change from the stale mechanics gamers are used to.

Eidos Montreal's Deus Ex: Human Revolution offers a similarly styled world. Nothing pops up to tell me how bad or good I've been. Everything is seamless. People just react to the things I do the way I would imagine a person would. Room for gray choices comes naturally in that design model, and it makes interacting with NPCs and the world as a whole that much more satisfying.

Meters and points can't offer that kind of experience, because all possibilities have to fall somewhere on that meter. The player ends up with situations where they can see something switch in the world. In Infamous and Infamous 2, crowd interaction changed the moment the point threshold broke. Suddenly, protagonist Cole MacGrath was either instantly liked or disliked. The programming of the entire world shifted right before his eyes. This didn't mark the revelation of The Matrix's hold on Empire City and New Murais; it was just a side-effect of a severely flawed set of metrics.

On one hand, I would argue that games like Infamous don't actually need these systems at all. The game doesn't seem to want one itself. When morality gameplay is added to the Empire City and New Murais, those weird Matrix-esque effects crop up and give everything an unnecessary coating of open-world clumsiness. Considering that Sucker Punch decided to completely abandon the evil arc of Infamous when they wrote the sequel, it would probably be better to just abandon that particular mechanic in favor of a richer, more streamlined narrative.

On the other hand, when morality is done right, it can be pretty amazing. What if the current Infamous and Mass Effect formula followed The Witcher 2's and Deus Ex: Human Revolution's examples by having the world react to Cole and Shepard organically?

The balance of action versus interaction in the setting makes the idea of choice feel natural and relevant to both the story and gameplay. It's a twisted kind of "less is more" logic, really. By removing the crazy bells, whistles, and omniscience of most morality mechanics, developers like CD Projekt RED and Eidos Montreal have proven that moral choice in games can become more than a fad that is showing its age.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More