John Spinale (pictured above) is the senior vice president of social games at Disney. He’s in charge of making sure the company takes its big brands and familiar characters into the social gaming market in the right way. He runs the Playdom division, which Disney acquired for $763.2 million in 2010 to help transition older brands into the new medium of Facebook and create hit games.

Spinale joined six months ago, after a stint as the top publishing executive at cloud-gaming startup OnLive. He has had a long career in games and has seen a lot of change. Hal Halpin (pictured below right), the founder of the Entertainment Consumers Association, interviewed Spinale in a fireside chat at our GamesBeat 2012 conference. Here’s an edited transcript of Halpin’s interview with Spinale.

[How do you look at the game world?]

John Spinale: We frequently started off taking a very platform-centric view of the world, which was a great way to look at it a couple of years ago. You had console games, PC games, games for kids, games on social networks, and games on mobile platforms. More recently we started to evolve to the view of, “These platforms are actually blending into one another; they’re starting to blur the boundaries.”

Social networks are tied into consoles, consoles are tied back into the social networks, and everything’s linked to the PC. Some are open and some are closed, but they all talk together pretty nicely now. So we’re starting to take a little bit more demographic or psychographic view of who we’re making games for. It’s still kids, but core gamers are going to want deep, rich gaming experiences, while some people want to have more casual, light, intermittent gaming experiences. People largely still on mobile platforms are going to want mobile games.

I mind the store for the social games side of things: casual games for either absolute casual, inadvertent gamers — the ones who find themselves on Facebook and are not self-identified gamers — or some of the midcore gamers who are starting to flock to social platforms, as well.

Hal Halpin: You entered the job six and a half months ago, at a time when the identity of social games was at a crossroads. Where it was a year ago, it could be identified really easily, and now it’s kind of nebulous….

Hal Halpin: You entered the job six and a half months ago, at a time when the identity of social games was at a crossroads. Where it was a year ago, it could be identified really easily, and now it’s kind of nebulous….

Spinale: Yeah. I mean, what’s a social game? I think that’s a fair question. Starting out with games on Facebook, or games on whatever social networks used to exist — MySpace and so on — those were social games. And now most games are actually connected to those platforms. Some are exclusively on those platforms, and some run on mobile, but they talk back to Facebook. So lately what we find is that socially connected games are not purely an online experience, but the bulk of the gameplay is doing your thing and then sharing and connecting with your friends to enhance the experience. And it’s still a fuzzy line that we draw.

Halpin: Being part of Disney, you have a tremendous amount of assets, brains, characters, and IP. How do you leverage all that, and what lessons have you learned?

Spinale: Historically at Disney, we probably haven’t done the absolute best job of being a games company. We’ve started off as a film company, then television, and parks, and continued to broaden out the portfolio of things that we did. But I think games until recently were more of an afterthought. It was viewed as a marketing extension of what we did. So, “Hey, here’s a movie. How do we make the game?”

That worked okay for the company, but I think when you look at the growth in the entire games business, it’s pretty obvious that this is a big piece of the media pie that’s just going in the right direction. Disney made a decision a couple of years ago to treat games as a first-class citizen. It really is quality first and consumer experience. What do people want? And then we’ll worry about how the details play out later.

That was the mandate given to us in the games group a little while ago, and I think you’re starting to see the by-products of that just now come out in the marketplace. If you look at us in any channel right now, Disney went from “who are they?” in the games space to stealthily owning the top spot or, at least depending on what cycle we’re talking about, getting into a top 10 spot.

Halpin: How do you differentiate between Playdom and Disney?

Spinale: For Playdom, we have two demographics: the casual players who wouldn’t ever call themselves a gamer but are actually playing millions of hours’ worth of games a month now, and we’ve actually started doing games for gamers as well. But again, the through-line for those two things is nobody expected to be playing games on Facebook, but they are. And once you get there, now the games market has been on Facebook for three-plus years. It’s a maturing market.

Spinale: For Playdom, we have two demographics: the casual players who wouldn’t ever call themselves a gamer but are actually playing millions of hours’ worth of games a month now, and we’ve actually started doing games for gamers as well. But again, the through-line for those two things is nobody expected to be playing games on Facebook, but they are. And once you get there, now the games market has been on Facebook for three-plus years. It’s a maturing market.

Standard things are happening to that maturing market. The expectation for quality goes up. It all started with text-based RPGs, where people were just chattering back and forth. You could make a game in a month or two. We had this horrible thing going on where we were cloning each other, and every company was coming out with its own derivative of whatever game the other guy had made a month before. It was pretty awful.

I think it was a bad experience for consumers. They didn’t know what was what, what was good, or what was bad. It didn’t really matter. I think the good thing for our market now is — especially being part of the Disney family — our mandate has been to make great products. Do that first, and when it’s appropriate, borrow from the Disney brands that we have around the table, whether it’s Marvel, Pixar, or an animated film. Or not, and create new brands, and actually feed those back into the pile of Disney intellectual property that we have. With that mandate, we’re very much out of the space of trying to keep up with the Joneses. It allows us to do things that are innovative.

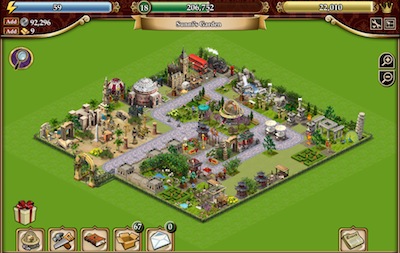

So, for example, in Gardens of Time, which is a social game on Facebook, what we did is take the concept of these hidden object games, which existed in the casual download space, pulled that into the social network space, and took something that was inherently a solo activity [and] turned it into a social activity. It had a really nice, cohesive product with characters, stories they could care about, and experiences that they could keep coming back to. Figure out how to monetize it in the free-to-play world. We did that on our own. There was nothing else out there in the market like that. It gives us the space to innovate and do things that are very relevant to consumers.

The same thing with Avengers Alliance, which was a game on Facebook for the more hardcore boys audience. We knew there would be an Avengers movie coming out at some point. It’s a very big franchise in the world of Marvel. We had these characters, and we thought we could come up with a great storyline and backstory that was exciting. Instead of making a movie tie-in, we kind of turned that upside down and said, “Let’s actually make a game first, in the same time frame, that will be relevant to the movie audience. But it’s also completely independent.”

We came up with the game earlier this year — four or five months before the movie launched — and we were able to build an audience on our own of 8 million players who were playing up until the time the movie came online. And that gave us the opportunity to start collaborating with the studios and Marvel, rather than just trying to hit their movie launch dates. The game was in development for two years. We had all the time and energy we wanted to make it a successful product in its own genre, and that’s an opportunity that we wouldn’t really get unless we were integrated into Disney.

We came up with the game earlier this year — four or five months before the movie launched — and we were able to build an audience on our own of 8 million players who were playing up until the time the movie came online. And that gave us the opportunity to start collaborating with the studios and Marvel, rather than just trying to hit their movie launch dates. The game was in development for two years. We had all the time and energy we wanted to make it a successful product in its own genre, and that’s an opportunity that we wouldn’t really get unless we were integrated into Disney.

Halpin: A few questions about tapping into your past and perspective…. You were there during the Eidos Lara Croft heyday. Where do you think the franchise is now, how to capitalize on it, and have they improved?

Spinale: In my career, I’ve been lucky enough to touch some really interesting intellectual properties at almost every company I’ve worked at. One of my previous employers was Crystal Dynamics at Eidos, which is now part of Square Enix. We built and grew Tomb Raider and Lara Croft, the intellectual property and character, that was turned into films and games. I was lucky enough to be the steward of that for a little while.

I think like many franchises, we learned the lesson that if you don’t make great games first and foremost, your audience will find other ones. You can have great characters and great stories, but in the game media world, you have to make great games. We strayed from that path. We put out some products that were average at best, and we were punished. We more or less had to sit out the PlayStation 2 era and start back up in the PS3 era.

What we saw at E3 looks great. I’m completely divorced from it, so now I’m all objective, but I think they’ve done a great thing. They focused back on making a great game, got away from the jiggling body parts, and turned it into a really exciting version of what it was known for originally: great stories, great characters, and really great gameplay that actually leverages physics and puzzles in the way that modern games can.

Halpin: Prior to Disney, you were with OnLive. What can they do now in a post-Sony/Gaikai world?

Spinale: I think when you look at the console market, it’s changing. Everybody gets that it’s changing. But I think there will always be room for high-end gaming experiences. People want really immersive game experiences. They want them on big screens, or they want them in their face with headphones, in addition to little tablet things or games on browsers.

OnLive is taking a stab — as are Gaikai and Sony — at pulling the console up into the cloud. I think that’s great. Having the ability to enjoy these incredible high-end experiences without having a $400 piece of hardware in the living room is amazing. Someone will crack that. OnLive took the route of actually trying to build out the infrastructure on its own. Maybe that will be the right way.

OnLive is taking a stab — as are Gaikai and Sony — at pulling the console up into the cloud. I think that’s great. Having the ability to enjoy these incredible high-end experiences without having a $400 piece of hardware in the living room is amazing. Someone will crack that. OnLive took the route of actually trying to build out the infrastructure on its own. Maybe that will be the right way.

Halpin: Moving from an entrepreneurial startup with all the challenges and excitement that there is with OnLive, and then going to the stability of Disney…what’s that like?

Spinale: It’s different, that’s for sure. When Disney said, “Let’s get serious about games,” they actually acquired the vast majority of the development resources we have. Club Penguin came in through acquisition, and Playdom came in through acquisition. We bought a company called Wideload, which is Alex Seropian’s thing after he did Halo, which was also working on console games for a time. Tapulous, Bart Decrem’s mobile group, came in through acquisition.

Whenever Disney is really serious about something, we’re a very acquisitive company. We can get very big. We brought in all these companies, and it’s great. But before that, Playdom itself was a very avid acquirer of companies. I think we merged 11 or 12 companies together over the course of the first two years of our existence. Every one of those was a startup between five and 50 people.

So what I inherited is a very entrepreneurial spirit. There are 500-plus employees, but they’re broken up into a bunch of little studios. We’re still getting the benefits of shared technology and infrastructure, but each one still has its own little business culture, and we really like that. It really doesn’t have any of the things you’d expect from a big company in terms of structured process dragging things down. It’s more the opposite.

Halpin: Your company’s historical background was taking all of these smaller companies and merging them into a conglomerate essentially, which Disney purchased. So is that pattern going to continue?

Spinale: Sure. So Disney acquired us [. . .] and the size of the acquisition was pretty large. That has enabled us to get into the top 10 in every category across the board pretty quickly, relative to where we were. I think we still think about things through that lens. We look at things very strategically: “What’s going to move the needle for the Disney corporation?” And then the other half of it is, “What’s going to help us functionally?”

Playdom just acquired a small developer in Hyderabad. The deal was just announced last week; [they] helped us to make the Gardens of Time franchise. They do a fantastic job. We’ve known them for a long time, we trust them and love them, and we made them part of the family just a few weeks ago. We kind of look at it from both sides.

Playdom just acquired a small developer in Hyderabad. The deal was just announced last week; [they] helped us to make the Gardens of Time franchise. They do a fantastic job. We’ve known them for a long time, we trust them and love them, and we made them part of the family just a few weeks ago. We kind of look at it from both sides.

Halpin: One of the things that’s been of interest to a large degree inside the industry is defining who is a gamer. I’m pretty sure that we’ve all come to the conclusion that we’re all, to one degree or another, gamers. And so the next question to me is, “What defines a game developer?” Because there are millions and millions of kids — especially in Generation Y, but definitely in X as well — where they’re creating content. Which, to me, is a huge opportunity for these guys, where there’s all these potential indie startups, and if they were to roll them up using their expertise, then you would have another Playdom kind of scenario….

Spinale: Yeah. Who’s a gamer? First, it blows my mind because again, it really is everybody. Again, companies like ours and Zynga’s have shown the world that this market opportunity is big. It might not be growing in the triple digits like it once was — in terms of the new, unexplored opportunities of people who wouldn’t call themselves gamers — but it’s still really big. And it’s still really growing.

There’s been this democratization of game platforms. Some of them are very open, and some of them are slightly closed, but they’re still really easy to jump into relative to building a console game where you need a team of 200 people. You can build an app with a couple of smart kids in a college dorm room, and it’s amazing. Then you start to hit the standard issues of, “Well, how do I get distribution? How do I get noticed in an App Store that’s got a million apps in it?” All that other stuff.

That’s where things with Disney work really well. We have distribution and marketing. Not only that, but we have brands that people care about. As long as we do the right thing by those brands — which is marrying them to gameplay experiences that are unique, tailored to the platform, and exciting — and extend our brand in the right direction, then you can have these breakouts. What we did for the indie developers, and what we say is, “How do we build a bridge between them and us?” Because we’re a big and sometimes difficult company to approach.

So more recently, we started having our own hack days — what we call “product innovation days,” where we open it up. We had one a couple of months ago, and about 100 small development groups — from one-man shops to little indies from around the world — came in to work with us in Palo Alto. We had a great time. We did some presentations showing how the world of Disney works. They did some presentations as far as pitching their products and their ideas to us, and we agreed to do some really interesting things with the people who come through that program and the games that come out of it.

So more recently, we started having our own hack days — what we call “product innovation days,” where we open it up. We had one a couple of months ago, and about 100 small development groups — from one-man shops to little indies from around the world — came in to work with us in Palo Alto. We had a great time. We did some presentations showing how the world of Disney works. They did some presentations as far as pitching their products and their ideas to us, and we agreed to do some really interesting things with the people who come through that program and the games that come out of it.

Halpin: We’re starting to see kids who are graduating from school with degrees in games and game programming, or even at the high school level. These guys, hopefully, are the ones that are going to find them and hold them up…. How do they approach you?

Spinale: There are a bunch of channels to approach us. The problem with being big is you can’t just say, “Hey, I have a great idea. We should make this game.” But if there is an organized, thoughtful business approach — from an indie developer with a very specific idea, to larger organized developers who are seeking publishing support, and to somebody who has a perfect marriage between their gameplay mechanic and our IP — there are a lot of different channels. We’re incredibly aggressive on the games side; we’re pushing things in the direction of connected experiences. There are a lot of paths.

Halpin: So you work really well together, between Disney Interactive and Disney Ventures and collaborative?

Spinale: Yeah. Disney Ventures is not a massive venture group. It is an entity that’s there to help find opportunities that are really synergistic with Disney, as well as stuff outside our portfolio [and] people who can do interesting things within our portfolio. They definitely play an important role in what we do, but they’re probably not the majority of ways that new partners come into the fold.

Halpin: The impact of crowdsourced funding — Kickstarter and all that…. How do you think that impacts that ecosystem?

Spinale: As a guy who’s been developing games the last 20 years, with a small break to build a platform in the middle, I think it’s great. It takes the problematic dimensions out of the situation. As an independent developer, historically I’d have to go to a publisher and say, “Hey, can you give me money? I’d really like to evolve this idea, flesh it out a bit, and turn it into a game.” In which case, you had to sell your soul, give away a piece of your IP, and give away a piece of your company. It wasn’t a particularly healthy relationship.

Spinale: As a guy who’s been developing games the last 20 years, with a small break to build a platform in the middle, I think it’s great. It takes the problematic dimensions out of the situation. As an independent developer, historically I’d have to go to a publisher and say, “Hey, can you give me money? I’d really like to evolve this idea, flesh it out a bit, and turn it into a game.” In which case, you had to sell your soul, give away a piece of your IP, and give away a piece of your company. It wasn’t a particularly healthy relationship.

I should say that it’s not an easy business on either side of the coin; I’m not faulting publishers. And on the flip side, you had to go do venture funding, and that has its own strings, as well, as far as what you need to do with your company down the road. I think once you have a look at a crowdsourced funding opportunity, you say, “Hey, I have this great idea,” and there’s enough people who believe in it that you can get it up off the ground. And then you have a lot more leverage when you come to talk to people when you’re looking for things like distribution. You know that this thing has an audience.

I think that the problems with those types of funding opportunities will also start to emerge, in terms of what happens in cases where things don’t go well. You’re not an investor in the company; you don’t own any assets when it goes bankrupt. You have a lot of other problems that emerge in the fallout from that.

Halpin: Yeah. I’m not sure that all consumers understand that when they’re investing in crowdsourced funding, like Kickstarter, they’re really just a pre-purchaser.

Spinale: Yeah. You’re buying the right to a copy of the game and a couple of bells and whistles, largely. Sure, every term’s different, but if it goes wrong, that’s when you’re going to have a whole lot of unhappy people. But when it goes right, it’s a fantastic thing. And so far it’s gone right more than it’s gone wrong.

Halpin: Going with that industry, you went to Activision as one of the first 20 employees, and there was a ton of IP, but that’s pretty much it.

Spinale: Yeah. So Bobby Kotick and a bunch of very smart guys with a lot of foresight bought the assets of Activision out of bankruptcy, and then they looked around and said, “Now we can do something with this.”

They hired me and a bunch of other guys to start building products. We owned all the Activision 2600 cartridges like Pitfall, River Raid, Kaboom, and then we also owned Infocom, so you had Zork and Enchanter — the work of all these incredible people who built this first generation of games. We got to work with them or take their intellectual property and spin it out into next-gen games. So that went from PC games to 16-bit console games back to PC games.

We wove our way back into being a pretty good company.

[Photo credit: Michael O’Donnell]

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More