What’s next for a designer of strategy games after working at Firaxis and Stardock, two of the few remaining studios making turn-based titles for the PC these days? Run over to Europe and catch on with a publisher such as Paradox Interactive?

What’s next for a designer of strategy games after working at Firaxis and Stardock, two of the few remaining studios making turn-based titles for the PC these days? Run over to Europe and catch on with a publisher such as Paradox Interactive?

If you’re Jon Shafer, you find another option: You start your own studio.

The lead designer for Civilization V and Elemental: Fallen Enchantress has founded Conifer Games, which you can find in the Detroit metro area. His first title is Jon Shafer’s At the Gates, a 4X (explore, expand, exploit, exterminate) turn-based 2D strategy game set at the fall of the Roman Empire. It’s due for a 2014 release.

“I am a creator. I’d rather be the person doing the design work, and I think this is the right way to do it — and the most fun for me,” Shafer said. “Obviously, Sid [Meier] has made that model work for a while now.”

Dumping the manager hat

Founding a game-design startup is all about making the game Shafer wants to create and doing it his way. He takes his inspiration from how hands-on Civilization designer Meier is at Firaxis (Shafer says he still does a great deal of programming and design) while divorcing the management duties that come with being a lead designer. It’s not necessarily about being indie — the freedom Shafer seeks is not just from big publishers but also big teams, which in his experience get in the way of making strategy games.

“[A strategy] game is a combo of systems that must work together well. It’s not an role-playing game where one person can do combat, another can do narrative, and another can do level design, and stitch it all together,” Shafer said. “With strategy, all go together seamlessly. You can’t separate the job. You have a vision and want to build it, and the number of nuances and details are immense. Your first and second drafts aren’t good enough. You must iterate.”

By starting a smaller studio, Shafer wants to close that design loop. He wants to be both the programmer and the designer. When he left Firaxis and went to Stardock, he tried to divorce game design from programming. But what he found is that he enjoys design work. “I had a conundrum — with larger teams, you can’t do it right,” he said. “You don’t have the time to do it right. You can’t ignore your team. You can’t lock yourself in a closet, and you don’t want to take the time from programming. The game can’t be as good.”

His conclusion? “What works for me is doing my own thing, starting something new, and for the development of At the Gates, I’m doing the design and A.I. programing, have another doing programming — a team of three, all living together — plus a few contractors. I can dig in how I want and spend time how I feel is best. It’s a ton of fun. It’s everything I wanted it to be. It’s what I wanted when I wanted to be off on my own.”

An evolution for strategy games?

An evolution for strategy games?

While making the rounds after the announcement of Civilization V a few years ago, Shafer said that he was a student of history — in particular, 19th century German history. But he’s had an interest in many eras of world history. The theme for At the Gates comes from discussions for a Fall of Rome-type scenario he had with a developer friend from Firaxis, Scott Lewis. (“You can blame him for this,” Shafer joked.)

“In a 4X empire-building game, you start small and build up over time. The Romans didn’t do that in the later stages [of their empire], but the barbarian tribes they were fighting with did. That same friend got me hooked on the History of Rome podcast — one of the best out there — and it all coalesced with my game-design ideas.”

At the Gates is different because of its “evolving map.” Things change. One turn equals a month, and 12 turns equals a year. As Shafer points out, the change of seasons had an influence on the events of Rome’s fall. “When the Rhine or Danube freezes over, you can cross over, whereas in the summer, you can’t get an army over,” hesaid.

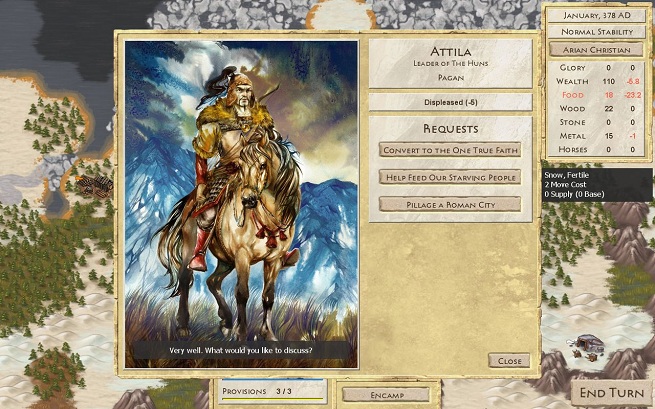

It’s also different because you’re not building an empire but seeking to save one — you’re destroying Rome’s crumbling corpse. This is an important distinction. “You don’t play as the Romans — you play as the barbarian tribes around them. The Huns, Goths, and Vandals,” Shafer said. “You have to move as resources expire.”

As At the Gates starts, the Roman Empire has already split into its Western and Eastern halves. Rome and Constantinople may be working together at this point or fighting. “At the beginning, they are tough. But they eventually get weaker and weaker,” Shafer said. “The progression is that you start with camps and build up over time.”

This is where the changing maps and eroding resources come into play. “The arc is different than in most empire builders and 4X games, where you get stronger and stronger and hit a point where you get so strong that no one can beat you,” Shafer said. This is where many players start new games as it’s just not fun to play out a scenario you can no longer lose.

“We wanted to get away from that,” he said. “One of the ways that we do is with depleting resources. You need food, wood to build improvements. In the early game, it’s fairly traditional. You go around, finding villages, resources, and uncovering the map. As the game gets in its later stages, the map runs out of stuff. The game climax is that your goal becomes to capture Rome or Constantinople, and you must do this before the map runs out of fuel.”

As your resources dwindle, you have two choices: Find more resources or take them from other barbarian tribes or the Romans. In many strategy games, you can sit and expand without fighting meaningful battles. That’s not going to happen in At the Gates.

“A big part of the game is trying to figure out where your next meal is coming from — during the first half, you can find resources pretty easily or capture iron mines or farms to keep economy going,” Shafer said. “But eventually, the easy pickings disappear. You must find new resources or take them from your neighbors. There is a military bent to the game — it’s a little bit more brutal.”

Shafter acknowledges this take isn’t going to appeal to all strategy gamers. “We wanted to do something fresh and interesting. The 4X genre is a great one, but there’s not a ton of innovation. Between seasons and a new arc to the game, it really spices up things.

“Unlike other strategy games, it becomes harder as you go.”

Making friends

Making friends

Rome need not be your enemy. At the Gates has a diplomatic system. Shafer says some parts are pretty traditional: A relations rating measures whether Rome or a tribe likes or dislikes you. You improve relations with fulfilling requests, such as delivering food to another tribe when you have more than enough to see you through the winter. “It’s like how giving a homeless person a meal would be happier than finding a random person while shopping and giving them food. The idea is that what you do really matters. There is this situational aspect that when you do something at the right time — what another needs right now — is more important than handing stuff out randomly.”

Since the Dark Ages aren’t exactly known for advances in technology, At the Gates lacks the standard tech tree found in strategy games. But Shafer wanted something to fill that hole, so you can gain perks on a “Romanization” tree. As you become more Romanized, you gain perks that act like technology — building ships or siege weapons or upgrading farms. “I feel it’s going to be more interesting than watching a science box fill up,” Shafer said. “Everything should be meaningful, important. You won’t be hitting ‘end turn’ for 10 or 15 times in a row to get to the good part.”

The name game

Shafer and his teammates (above) founded their studio in Detroit, which is slowly becoming a fertile ground for startups and tech companies. They bought a house in a green patch full of trees in the Detroit metro area. “It’s got some woodlands and stuff,” Shafer said. “And a lot of pets. Including a parrot. Kaye [the team’s artist] has a domestic Siberian fox and a sugar glider. And we wanted a name that fit with that.

“Everybody tries to come up with a name of their company that fits their values. We wanted a name that’s short and snappy, easy to remember, easy to spell. At the two previous companies I worked at, Firaxis and Stardock, everybody I’d tell about my work would say 1) ‘What?’ and 2) ‘How do you spell that?’ I would rather get the question ‘Where’d you get that name from’ than ‘What!’”

Money matters

Conifer has been working on At the Gates for several months and already has a fully playable prototype. Shafer said he and his teammates have funded the game with their own money (technically, he’s the studio’s only full-time employee. The others have day jobs).

So, where’s the money coming from? From you. Conifer is taking At the Gates to Kickstarter, setting a $40,000 goal. “Obviously, that’s not a lot for an in-depth strategy game. The reason this is possible is that we have so much progress already. We have to do more iteration, more A.I., lots of miscellaneous things. Hotseat support. Smaller things you don’t think about that, if not there, people say you really didn’t do a good job for this thing.”

The Kickstarter goes live today, and the $40,000 is the minimum Shafer says he needs to finish At the Gates.

Kickstarter is important to indie development, Shafer says, because many games that appear on it just wouldn’t receive funding from a traditional publisher — “A 2D Fall of Rome? No one would do it,” Shafer said. But what is truly the key for developers of strategy games is digital distribution. “If I had to print CDs and manuals and ship stuff and have meetings with Best Buy and Walmart … a lot of big-box retailers wouldn’t be interested,” Shafer said. “Between these two [Kickstarter and direct download], we can get it made and get it to the people. In the past, being a small indie company was challenging and risky.

“Now, all you have to do is make a good game — a challenge that’s more up my alley than getting a game on store shelves.”

Image source: Conifer Games

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More