This is part of our ongoing series about games and trends of the upcoming next generation.

The Witness is a game about drawing lines on panels, and yet creator Jonathan Blow thinks that it is going to take players more than 30 hours to complete it.

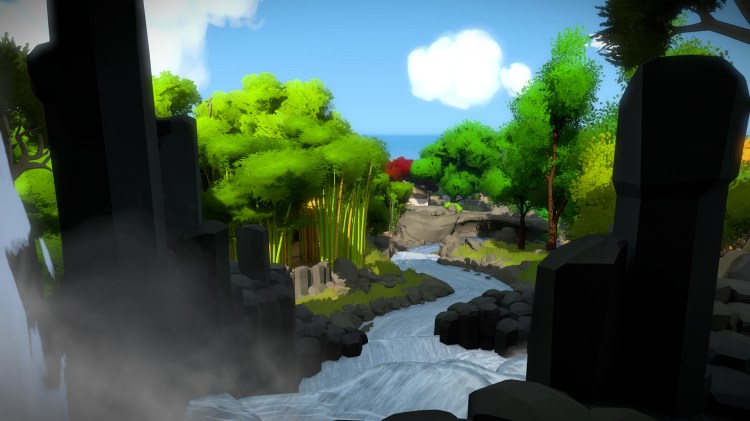

Of course, it’s reductive to say that The Witness is only about drawing lines. It’s likely about a lot more than that. Blow layered the puzzles with metaphors, and he intends to add story elements through BioShock-style audiologs before it debuts — but when players aren’t exploring the open-world island setting, they’re almost always solving line puzzles.

So that prompts a question: How can a game with such a focus on a single gameplay mechanic last 30 hours? Hell, it’s potentially a lot more than that.

“How many hours do you think it is, roughly,” Blow asked his co-designer, Orsolya Spanyol.

“For people who’ve never seen these puzzles,” she said while considering for a moment. “It’ll probably be as much as 50 hours, I’d imagine.”

To this, Blow couldn’t help but give something of a helpless smile. Almost like he hadn’t quite realized how massive of a game he was making until that moment.

“I don’t know,” said Blow. “That’s a high number. There’s just a lot.”

When Blow set out on his next project after releasing the 2008 platformer Braid, he knew that he wanted to work on this line-game puzzler. At the outset, however, he was intending to build something around eight hours long.

“Maybe it’d be 10 hours,” he said. “And now it’s three or four times that. Just because it felt incomplete not to go everywhere that it could go.”

While we were talking, I played for what felt like 15 minutes (although maybe it was much longer). I started right at the beginning and could feel the game nudging me with nonverbal indicators of how I should think. At first, I was just guiding a line through premade designs, but soon I was facing complicated patterns that had unspecified rules.

For example, one puzzle that I struggled with had diamond shapes as well as black-and-white circles scattered across it. I learned from an early puzzle that I was supposed to draw the line over the diamond shapes. I also thought I learned — again from other puzzles — that I needed to separate the white-and-black circles.

Something wasn’t working, but I could feel things starting to click.

“Some adventure games will be like, ‘Here’s the diagram that tells you the answer to this puzzle in the other part of the world.’ The Witness is never that,” said Blow. “It’s always something that you have to figure out. What becomes interesting is all the different ways that there are to have the environment indicate a solution to you. That’s actually kind of crazy.”

While the line/maze puzzles all occur on these panels, the information you need to solve them often live in the world. Again, this doesn’t mean Blow is hiding a piece of paper with a map on it.

After letting us explore, Blow took over the controller and started to show us the rest of the world. He zoomed over to a different area that exemplifies how he and Spanyol are incorporating the world into the puzzles. It was another panel that looked very simple, but when he tried to solve it, nothing was working. He revealed that you needed to look at the panel from the other side of a tree. When looking from the correct perspective, that tree’s branches and leaves revealed the correct path to solve the panel.

This is how Blow communicates to the player without words, and he apparently had enough to say to fill up a game with potentially 50 hours of content.

“We just keep taking it to new places. That’s why it’s such a long game,” he said. “It’s not just that the puzzles are interesting. It’s that as you go further and further into the game, it’s like, ‘Yeah, I never realized that just the idea of a little panel that you trace a line on could lead to this many different things.’ That was the surprise in development, too. That’s one of the reasons it ended up such a big game.”

Those surprises also made the long development interesting.

“It was the most fun design time in my life,” said Blow. “There was a lot of stuff to design, but it also makes it a big game to play.”

Related articles

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e56afbab-acb3-4643-8eac-5fe07a1de213)