Hail Mary

Rick Thompson (pictured right) never quite believed that the numbers would work. He opposed the hard drive, but had to accept it.

Rick Thompson (pictured right) never quite believed that the numbers would work. He opposed the hard drive, but had to accept it.

Thompson figured the company needed to spend more than $1 billion before it saw a dime of revenue. In a slide presentation entitled “Hail Mary,” Thompson showed Gates the grim numbers on Dec. 21, 1999, when there were about 60 people working on the Xbox.

“If you do this,” Thompson said in a presentation to Gates. “You will lose $900 million over eight years.”

“Can’t you do better than that?” Gates complained. It got worse. If Microsoft were forced to match Sony in a price war, Microsoft would lose $3.3 billion. Revenue from online gaming became a wild card. No one knew if it would take off or if a proposed service that Allard was working on, Xbox Live, would ever work.

Robbie Bach said, “This is a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle on a good day.” Thompson made more rounds to game publishers, checking to see if companies such as Japan’s Square would agree to be acquired. But the Square executives wanted to sell 40 percent of the company for more than $2.5 billion.

“It was a laughable price,” Thompson said.

Still, Microsoft had the cash. It was generating $1.5 billion in cash every month from its Windows and Office businesses. Microsoft had $30 billion in cash, while Sony had $5 billion and Nintendo had $7 billion. Even with all that money, Ed Fries wanted to grow the game business more organically, and Bill Gates eventually agreed that was the way they would go.

The Valentines Day Massacre

Unfortunately, journalists were sniffing around and they got wind of the Xbox.

Tom Russo, a senior editor at Next Generation magazine, got hold of a rumor and confirmed it with the help of his boss Chris Charla. They ran a story about the project. I followed with a story in the Wall Street Journal on how Microsoft planned to spend billions on the project.

When Sony officials read about it, they finally had a handle on how serious Microsoft was about the video game market. Before that, it was really unclear whether Microsoft was committed, said Molly Smith, former head of corporate communications for Sony’s U.S. game division.

“I wouldn’t say we were dismissive,” Smith said. “But we were puzzled. There were plenty of projects like tablet computers that came out of Microsoft but never really went anywhere.”

Ed Fries (pictured right), the former game studios chief, still has vivid memories of the “St. Valentines Day massacre” in February, 2000. That was the name for an all-day meeting at Microsoft that went into the evening. Bill Gates started out asking why they were getting into this crazy business and it went downhill from there. The meeting was part of the final review for the team and whether Microsoft would go forward or not.

Rick Thompson, who was the general manager at the time, recalled, “We looked around at the table and asked if we really wanted to lose billions of dollars over eight years.”

Fries had to explain his plan for developing the Xbox games with a divided staff, with half the developers focused on PC games and half focused on the Xbox. J Allard was impatient with Thompson and said, “We have to stop fucking around.” Allard wanted to move forward and keep the rest of the company out of his way. Gates asked for explanations of the dozens of decisions the team had made. Some of them were quite technical, like Cam Ferroni’s view that games should access the kernel, or the lowest level of the operating system, so they could operate with the utmost speed.

Steve Ballmer said, “If we do this, we don’t ever revisit this decision. We support these guys.”

As the meeting closed, everyone was exhausted. Everybody had to step out of the meeting and tell their wives that they wouldn’t be home for Valentine’s Day dinner. The meeting because known as the St. Valentines Day Massacre because it slaughtered a romantic evening with spouses. But in the end, the Xbox, with its glowing green orb, got the green light.

Bachus, Blackley and others had to line up demos for the announcement, so they hit the road again to pitch publishers around the globe. Fries had to get moving. He had 400 game developers at 10 internal studios and relations with 20 outside studios. They had to get focused on making games for the Xbox. The creative talent needed a considerable amount of time and freedom to cook great stuff.

At one point, Gates asked Fries, “Do we need those cute mascots? Do we have any?” Fries considered buying Midway Games, a struggling game publisher, but Fries didn’t feel like there were many assets to be gained. Still, he knew he had to at least double the size of his game studios to pull it off.

Chip shootout

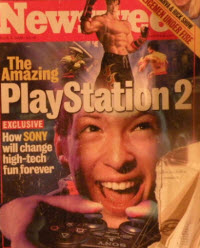

Just after the approval meeting, Newsweek ran a fascinating cover story about the “Amazing PlayStation 2” and how it would change gaming technology forever. It was about how Sony wanted the box to be so much more than a game machine, and it was the manifestation of Microsoft’s worst fears. The PS 2 was going to let gamers “jack into the Matrix,” claimed Ken Kutaragi, head of Sony’s PlayStation business. It was going to be a “digital delivery system” for Sony games, software, tunes and services. It was a convergence play.

Microsoft, by contrast, had decided to focus on games, games, games. It too wanted to head Sony off from being the gateway to home entertainment, but the way to do that was through better games, Blackley said.

That meant that the final hardware for running the games was critical. Choosing the final graphics chip was a vital decision, but one that was dragging out. Jen-Hsun Huang (pictured below), chief executive of Nvidia, wanted the big deal, which could be a huge boon for his graphics chip business. But he didn’t want to sell Microsoft chips at a loss.

Game developers like Wyatt insisted on using Nvidia because developers were so familiar with making games for it. But Nvidia’s price quotes were much higher than what others offered. Rick Thompson felt like he had been sold a bill of goods, and it took Blackley and Bachus and others a lot of effort to keep Nvidia in the bidding. The nuances of chip economics were new to Microsoft. The price depended on the size of chip, its yield, complexity of design, and ability to be manufactured all came into play.

“I wanted to do the deal, but not if it was going to kill the company,” Huang said.

“I wanted to do the deal, but not if it was going to kill the company,” Huang said.

Thompson started to favor a pitch that came from the WebTV team, which wanted to get back into the project. Team members had unearthed graphics chip design house GigaPixel, which promised to design a brand-new graphics chip with WebTV’s engineering help. Thompson believed that if Microsoft owned the chip it created, it could save a huge margin and control its own destiny at the same time.

Thompson chose to move ahead with GigaPixel. George Haber, head of GigaPixel, was delighted. Microsoft would invest $10 million in GigaPixel and pay $15 million to help develop its chip. If GigaPixel later went public, Microsoft would make so much money on the investment it would essentially get its graphics chips for free.

Haber got a call from Nvidia’s Huang, who hinted in not so polite language that if he did the deal, Haber would be beholden to Microsoft for life. But Haber went ahead. Gigapixel moved its 33 employees into the WebTV building in Mountain View, Calif., and Haber gently taunted Huang — a conversation he would later come to regret.

Within the Advanced Technologies Group, there was dismay. To them, GigaPixel was nothing but a bunch of promises.

“This was the worst decision in the entire project,” Rob Wyatt (pictured right) recalled. “Remember, this chip didn’t exist, the proposed architecture was new, and different from their prior design. We never got a working version of that. This was when programmable graphics shaders were coming out and GigaPixel had never made a programmable chip. We knew the box would fail if it used this hardware.”

“This was the worst decision in the entire project,” Rob Wyatt (pictured right) recalled. “Remember, this chip didn’t exist, the proposed architecture was new, and different from their prior design. We never got a working version of that. This was when programmable graphics shaders were coming out and GigaPixel had never made a programmable chip. We knew the box would fail if it used this hardware.”

The ATG team fought to keep Nvidia alive. The chip schedule pushed the launch date into 2001. Chip makers often needed two years to make chips. But Microsoft was pushing a schedule that would give chip vendors a little more than a year to do their work. Wyatt argued so much that he eventually got fired.

The Xbox was originally scheduled to be launched at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, 2000. But the team pushed that back to March. The extra time before the announcement gave Thompson a last chance to revisit his deals. He tried to buy Nintendo again, but balked at the $25 billion price and the Nintendo executives didn’t want to sell anyway. Microsoft’s proposal was to have Microsoft provide the hardware for Nintendo, which would focus only on making software. To Nintendo, this seemed ludicrous, since Microsoft had never made hardware before.

Meanwhile, some engineers proposed creating a companion handheld, the Xboy. But Bach nixed the idea, saying he had to keep his eye focused on the console business. Blackley, meanwhile, lined up some cool demos from Pipeworks and the animation house Blur Studio to create “eye candy” demos for the Xbox unveiling. When Blackley saw Blur’s work, he called them up and said, “This is fucking great!” He was all set for the unveiling at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco in March, 2000.

At the very last minute, just before the announcement, Nvidia got back in the game with a new proposal to fuse two chips together. Word leaked out about GigaPixel and the game developers, convinced that the console wouldn’t work as well with a new chip as it would with the Nvidia hardware they were familiar with, revolted. So Microsoft and Nvidia finally signed a deal. Microsoft would pay up to $48 a chip for the first 5 million chips and would also pay Nvidia $200 million in an upfront fee. Thompson visited Gigapixel at WebTV the next day and announced, “We signed a deal with Nvidia last night.” Haber and the employees were stunned.

“If we hadn’t caused such a stink, we wouldn’t be talking today,” Wyatt said a decade later. “Nvidia had their own issues, but they had a working chip and were willing to work within our limits and redesign it to make it work.”

Similarly, Advanced Micro Devices thought it had a deal clinched to provide the microprocessor for the Xbox. That was true until the night before the announcement. Paul Otellini, one of the top executives at Intel, convinced Bill Gates that Intel could provide the chips. Intel clinched the deal and the AMD employees were dumbfounded when they heard the news at the announcement.