The GDC Unveiling

At the Game Developers Conference, the Xbox was an open secret. Bill Gates was giving a keynote before 5,000 developers and referred to the mystery box under the black cloth as a “very deep secret,” getting chuckles from the crowd. He teased the audience and finally announced the Xbox, unveiling Horace Luke’s chrome “show box.” Blackley came out on stage and ran the demos. Everything went smoothly.

At the Game Developers Conference, the Xbox was an open secret. Bill Gates was giving a keynote before 5,000 developers and referred to the mystery box under the black cloth as a “very deep secret,” getting chuckles from the crowd. He teased the audience and finally announced the Xbox, unveiling Horace Luke’s chrome “show box.” Blackley came out on stage and ran the demos. Everything went smoothly.

Game developers loved the fact that the machine had an Ethernet port and a hard drive, opening up great possibilities.

“The future of entertainment was right there in every box,” David Hufford, the PR guy, said recently. “The Ethernet port and the hard drive. Those features said the future will be open. It will be social. It will be digital. It will be more than games.”

Microsoft won over developers in part by asking them what they wanted, and then actually listening to what they said. Microsoft was dreaming big and it wanted to partner with the greatest minds in gaming to bring their ideas to life.

“We made it uncool for platform manufacturers to ship sub-par developer tools and support, forever,” said Drew Angeloff.

As an example, Microsoft didn’t try to create its own development system with its own compilers and adapters. Rather, it extended its own Visual Studio tool from the PC, enabling developers to take advantage of the thousands of hours that had already gone into learning and refining this tool.

Chris Prince, a member of the Advanced Technology Group, recalled that the Advanced Technologies Group figured out how to create a tool called PIX, or Performance Investigator for Xbox. PIX allowed a developer to have an unheard of level of introspection into why a part of the game was or wasn’t working. They could pause the game, focus on something as small as a pixel, and see the entire sequence of computations that led to the pixel showing up on the screen at that particular time. No one else had created such a tool.

The Elevator

That night, the team partied, with many gathering at Scott’s Seafood in San Jose, Calif. The team ordered champagne. Nearby, developers from Ensemble Studios started a chant, “Xbox! Xbox! Xbox!” and pounded the tables. The headwaiter was fuming as most of the restaurant goers began doing the same thing. Jeff Henshaw went around from table to table apologizing to other guests, asking if he could pick up their tabs if they were annoyed. He paid for about 10 dinners.

After the dinner, Drew Angeloff suggested they all pile into the elevator. Blackley was the last to pile in. As he jumped in, the elevator was already sinking. Angeloff thought Blackley would get decapitated. Then the elevator dropped and slid almost four floors. It stopped halfway between floors and the occupants had to pry the door open. Horace Luke, the designer, was shouting, “My leg, my leg!” (He turned out to be okay.) Kevin Bachus said later that he had counted 24 people in the elevator. Half the team wanted to run, while half wanted to stick around and tell somebody what had happened.

“You could tell who grew up in bad neighborhoods,” Blackley said.

The day after it happened, I asked Blackley about the elevator incident. He said, “A team that doesn’t have fun can’t make a fun product.” Blackley’s father called him up to congratulate him when the story ran in the Wall Street Journal. Around that time, I started thinking that this story had the potential to be a book. Robbie Bach shuddered when he read the story in the newspaper and told the instigators, “Remember, you guys are representing Microsoft.”

A little game called Halo

Even though the console was now on track to launch, Rick Thompson, who had tried to believe in the business, finally decided to give up. Too many deals failed to come through and he was worried about the profitability of the venture. “I said we were not on the right path,” Thompson said. “I said it 50 times. I was consistent all the way. Only by some miracle in the business model could I see us making money sooner.”

He resigned as general manager and Robbie Bach took over as “chief Xbox officer.” The process of greenlighting games began, with a fabled “Star Chamber” voting yay or nay on proposals.

The camaraderie continued. In a prototyping lab with a lot of dangerous equipment, Rob Wyatt yelled at Drew Angeloff, “Get away from me with that blowtorch, you skinhead.” The quote made it into Time magazine as a reporter was visiting at the time.

And Nvidia wound up buying Gigapixel, netting the spurned George Haber $37 million as part of a $186 million stock deal.

The Xbox team expanded dramatically, growing to 1,000 employees through the summer of 2000. Another 5,000 to 6,000 third-party developers were working on games. Microsoft was winning the hearts and minds of the industry. Electronic Arts CEO Larry Probst said privately he would welcome Microsoft, as it made him less dependent on Sony.

Ed Fries had been busy getting dozens of games ready for the Xbox launch. But no one knew exactly what the killer app would be. Luckily, a planner named John Kimmich had been scouting developers and came upon Bungie, which was on the verge of something big. He visited Bungie in Chicago along with studio executive Stuart Moulder.

On June 19, 2000, Ed Fries announced that Microsoft was buying Bungie, which was working on a promising title called Halo. Bungie had never sold more than 200,000 units of a game, but it was considered a star Mac developer. Microsoft was able to pick it up for about $30 million. It was the bargain of the century. The full staff relocated to Redmond.

But first, Fries had to take a phone call from an irate Steve Jobs, who raged about how Microsoft had just raided the best developer of games for the Mac. To mollify Jobs, Fries had to appear at a Jobs keynote speech and promise support by making Mac games.

Jason Jones (pictured above), the technical lead on Halo, was excited about adapting the first-person shooter game from the PC to the Xbox. His team focused closely on mapping the shooter controls to a game controller’s buttons, and figured out how to assist the user’s aim with a little automated nudge in the right direction. The small team had barely 10 months to get the game ready for a fall 2001 launch. That was now the appointed time for the launch of Microsoft’s first game console. They wanted to do a game that couldn’t be done on any other console.

Meanwhile, the team gained more expertise. After seeing a demo from Bachus and Blackley, Brian Schmidt joined the Xbox team as an audio expert. His mission was to integrate Dolby Digital 5.1 surround sound into the Xbox. Digital surround sound hadn’t been done before in gaming, and it wasn’t an easy process to pull it off. Negotiations between Dolby and Microsoft lasted months.

Schmidt gave a demo to Bill Gates one day as he was passing through on a tour. At the end of the day, Gates met with 200 team members in a cafeteria. Asked what was the coolest thing he saw that day, Gates mentioned the “audio stuff.” At that point, Schmidt felt the admiration of 200 pairs of eyeballs on him. Thanks to Schmidt and others, gamers would be able to listen to that pulse-pounding music and cacaphony of gunfire in Halo in surround sound.

Gathering momentum

Sony’s PlayStation 2 was gathering steam. It had launched in Japan in March, 2000, and sold more than a million units on its first weekend. It effectively killed Sega’s Dreamcast, which until that point had been a scrappy little console with potential.

Then Sony lined up a U.S. launch for October, 2000. It looked like it would be in the market for a full 20 months before Microsoft sold its first machine. Meanwhile, Nintendo was readying a console called the GameCube.

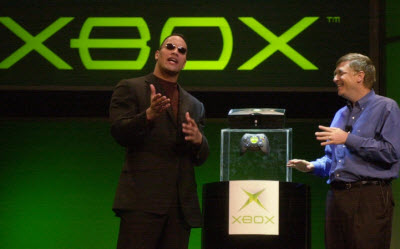

Microsoft’s planners had become hopeful that it could sell 100 million Xbox consoles over four years. But the long delays in choosing chip vendors were coming back to haunt it. Nvidia was rushing to get its graphics chips done on time, and contract manufacturer Flextronics was scrambling to get its assembly line in place. Everything was coming down to the wire. At the Consumer Electronics Show in 2001, Bill Gates and Seamus Blackley showed off the real Xbox design, a black box with an X and a green orb in the middle. The wrestling champ “The Rock” came out on stage, helping make the Xbox seem cool. The crowd loved it when, in good humor, The Rock verbally put down Bill Gates, the richest man in the world, quipping “Nobody cares what you think, Bill.”

“One of the basic premises of the Xbox is to put power in the hands of the artists,” Blackley told the crowd.

Later, at a Gamestock event in Redmond, Ed Fries got to show off Microsoft’s first-party titles for the Xbox. Again, he emphasized how games could become a form of art.

“The thing that is happening with technology that is so exciting to me is we are finally leaving the cartoon world behind,” he said. He noted how some of the characters in the best games, like Metal Gear Solid, didn’t even have eyes. There was only so much emotion you could build into such characters.

“We have an epic battle,” Fries said. “You’ve got the world’s largest software company fighting the world’s largest consumer electronics company and arguably the world’s largest toy company, and they’re all spending billions of dollars to push this business forward.”

More than just a battle, Microsoft’s bet was that games could aspire to be more than mindless entertainment.

“A great book, a great movie, a great play — they are about more than just killing time,” he said. “We need to create art. If we take that seriously, if we focus on making art, not just entertainment, then I think for the first time we’ll deserve to speak to the mass audience and inherit our rightful place as the future of all entertainment.”

He showed off a bunch of games, closing with Halo. It was an inspiring speech, but there were some duds in the line-up that truly weren’t works of art.