Update: This two-part series is now available as an e-book for the Amazon Kindle for your reading comfort.

Editor’s note: This story is the first of two articles on the 10th anniversary of the launch of Microsoft’s Xbox video game console, which debuted Nov. 15, 2001. The narrative is based on recent interviews as well as my two books: Opening the Xbox: Inside Microsoft’s Plan to Unleash an Entertainment Revolution, published in 2002; and The Xbox 360 Uncloaked: The real story behind Microsoft’s next generation video game console, published in 2006. This piece follows the Xbox from conception to launch. Part two of the series traces the history from launch through today.

Microsoft launched its Xbox video game console a decade ago this week. Nobody expected it to succeed. The skeptics were out in force when the giant-size console launched on Nov. 15, 2001.

But it turned out to be successful beyond Microsoft’s wildest expectations. Microsoft lost (or, more politely, invested) more than $4 billion in the first console. But it has created an entertainment business that is now much more valuable than that, said Robbie Bach, the former head of Microsoft’s game business and the highest-ranking executive who was present at the beginning of the project through his retirement last year.

Microsoft’s second console, the Xbox 360, and the game business that goes with it are now churning out more than $1 billion in profits a year in what has become Microsoft’s most successful diversification to date. The making of the Xbox was a historic event that changed gaming forever, allowing Microsoft’s brand to be associated with something cool and sexy for the first time.

The console finally helped Microsoft wedge its way into the living room with a device that people craved. Now that box is a gateway to internet services, from online games to streaming video. The Xbox Live online gaming service, launched a year after the Xbox in 2002, represents Microsoft’s greatest achievement in the social market that has become key to engaging users for the long term. Not only did it create a true connected console and make online console gaming a reality, Xbox Live created an ongoing relationship with 35 million gamers and a live service that could be updated through software changes, not the introduction of new hardware.

“Today, the TV screen is just one of several where you want entertainment and other experiences,” Bach said a couple of weeks ago. “Xbox plays a central role in delivering that. It is now more than just gaming, but includes social interaction, video, TV, movies, and communications like Skype.”

For gamers, the Xbox brought a whole new landscape to gaming. Before, first-person shooters were a lucrative domain on the PC. But with the launch of its massive hit Halo, Microsoft migrated the first-person market to the game console. More broadly, consumers got to see the benefits of increased competition at a time when Sega’s failure had consolidated the market into two rivals. The result was a whirlwind of better games, improved graphics, and innovations in game play.

“More generally, it played an important role in making gaming a mainstream form of entertainment and broadening it to include video, music and other forms of entertainment,” Bach said.

Microsoft didn’t defeat its rivals Sony and Nintendo, but it has earned a measure of respect for its accomplishments in games. There’s no denying that Microsoft is now a force to be reckoned with.

A decade later, the original Xbox team has scattered to the winds. But we caught up with a number of the key members of the founding team to get their perspectives on the tenth anniversary of the Xbox.

“It feels awesome how it turned out,” said Seamus Blackley, one of the Xbox founders. “Xbox seems like a de facto, foregone conclusion in the history of games. It wasn’t. It was a tenuous thing for the first year. It is a testament to the people who made it happen.”

Before Xbox was born

At the beginning, Microsoft started with very little. The company had scraped together a game business with popular niche titles such as Microsoft Flight Simulator. In 1995, the team had about 150 game developers. At that time, Ed Fries took over the business and commissioned a game that would become a monster hit: Age of Empires, produced by Ensemble Studios in Dallas. It debuted in the fall of 1997 and Fries used the profits from that business to justify an expansion of the game development studios.

But Microsoft had no presence in consoles. By comparison, Sony had carved out 47 percent of the game console market with its PlayStation, soaring past both Nintendo and Sega on the strength of a flood of cool games.

Microsoft tried many times to create set-top boxes or game boxes for the living room that never saw the light of day. Sega agreed to use Micrsoft’s software for Dreamcast games, but that partnership went nowhere.

Meanwhile, in the 1990s, a trio of engineers that nicknamed themselve “the Beastie Boys” arrived at Microsoft. Three rather large, physically-imposing engineers — Alex St. John (pictured above), Eric Engstrom, and Craig Eisler — were renegades of the empire. In a strategy document dubbed Taking Fun Seriously II from 1995, they noted that Sony depended on third-party developers for much of its content and so it was vulnerable to having those developers lured to another platform. They thought the winning game platform would be the PC, which could adopt new technology a lot faster.

They saw the future of 3D graphics — then the domain of Silicon Graphics supercomputers — coming to the PC. To capitalize on that, they created DirectX, a set of technologies that enabled 3D software to run on a computer. DirectX would make it easy for game makers to create 3D games without having to port their games to every single graphics card that could be plugged into a PC. Spurned by their official bosses, the “Beastie Boys” worked on their own, stealing resources to make DirectX viable.

DirectX enabled the PC to take advantage of the enormous boosts in 3D graphics and keep up with consoles such as the Sony PlayStation. Were it not for DirectX, Microsoft would have had no foundation at all to build a software-based games business.

To court game developers, St. John threw lavish parties, like one themed Pax Romana, complete with “slave girls” and a Playboy Playmate who auctioned off guests to the audience. Maybe it was tasteless. But the industry adopted DirectX, embracing it even to the point where Microsoft’s proprietary Talisman graphics chip architecture never got off the ground.

Sadly, St. John got himself into hot water after he ordered a $2 million alien spaceship to be built as part of a gigantic game promotion. Then he got himself fired after he mouthed off in a “fuck you all” way, in a dripping-with-sarcasm response to criticism from a colleague. Then Microsoft found that the PC alone wasn’t quite enough to conquer the game industry.

A state of panic

One of the apocryphal stories was that Bill Gates approached Sony’s CEO, Noboyuki Idei (pictured right), before the PlayStation 2 game console was announced. Gates wanted Sony to use Microsoft’s programming tools, but Idei turned Gates down. Idei said that Gates flew into a rage, taking the affront surprisingly personally. Later, Idei said in an interview with Ken Auletta of the New Yorker, “With Microsoft, open architecture means Microsoft architecture.”

Sony’s decision not to depend on Microsoft was no surprise. Everyone in the tech industry knew not to turn their back on Microsoft, based on what happened decades ago when IBM gave its PC operating system rights to Microsoft. So Sony decided to make its own software for its machine.

Sony announced the PS 2 on March 2, 1999. Sony game chief Ken Kutaragi called it a “revolutionary computer entertainment system set to reinvent the nature of video games.” Trip Hawkins, who ran the rival 3DO game company, called Sony’s box a “Trojan Horse,” meant to get into the home as a game machine and then becoming the gateway for all home entertainment. With such a machine, no one would need a personal computer in the home. Andrew House, then-senior vice president of marketing at Sony’s U.S. game division said that Sony had broader ambitions.

“If it is just a game console, then we have failed,” he said.

Gates had seen it coming. After his meeting with Sony’s Idei, Gates returned to Redmond, telling his people that Sony wanted the PS 2 to compete with the PC, that it was going to be more than a TV set-top or game box: It was going to be a threat to Microsoft’s Windows franchise. (Gates recalled the meeting with Idei as amiable.)

The PC and consumer electronics were on a collision course, and the press was already talking about a “post-PC era.” Gates held a strategic retreat where his executive team focused on two pillars, the first based on productivity software such as Microsoft Office, and the second based on home computing and entertainment. At the end of the retreat, the executive team decided it had to delve deeper into gaming and come up with an answer to the PlayStation 2. Games were on the cusp of breaking out into the mass market and could even become bigger than the movies. The fear that Microsoft would miss out on this lucrative market flowed down from the top.

The Four Musketeers

At Microsoft, fear also bubbled up from the bottom. The four ringleaders identified by Microsoft as the founders of the Xbox were Kevin Bachus, Seamus Blackley (pictured right), Otto Berkes and Ted Hase. They banded together to push the idea of a Microsoft game console based on its DirectX technology as a counter to Sony’s planned PlayStation 2.

At Microsoft, fear also bubbled up from the bottom. The four ringleaders identified by Microsoft as the founders of the Xbox were Kevin Bachus, Seamus Blackley (pictured right), Otto Berkes and Ted Hase. They banded together to push the idea of a Microsoft game console based on its DirectX technology as a counter to Sony’s planned PlayStation 2.

Hase was a developer relations evangelist, and Berkes was a one of the most respected computer graphics experts in the DirectX group. Berkes wanted to create a version of the PC that could be tailored to run games and be built inexpensively. They wanted a machine that made content creation easy.

The loudest of the group was Blackley, a former physicist and the creator of Trespasser, one of the great failures of the game industry. It was a dinosaur game, made for Steven Spielberg’s DreamWorks game division, that promised great things such as physics-based game play. But the game chewed up a huge budget and crashed and burned when it came out. As his personal penance, Blackley took a job at Microsoft after that, hiding out and working on high-end graphics in obscurity. However, he had earned himself a great life experience: how to take risks and bounce back from failure.

Bachus was an evangelist for DirectX. He had worked at a game publisher and joined the DirectX team, just as St. John got fired. He had an encyclopedic grasp of games and became Blackley’s Microsoft sidekick. As the PS 2 worries spread, the musketeers decided to create their own console, based on DirectX. The secret, politically incorrect code name was Midway, cleverly named after the World War II battle where the Americans finally kicked the asses of the Japanese.

“The PS 2 was a huge motivator,” Hase said. “But we saw the PC as a creativity platform that could be made economically more attractive.”

Bachus and Blackley wanted a machine that met the needs of game developers, who had always had hardware shoved down their throats. Early on, Bachus sought to bring a sense of “empathy and responsiveness” to Microsoft’s approach. In the past, every Microsoft effort in the game industry had failed because of a failure to listen to customers or partners. Bachus came from the game industry and could understand the complaints that game creators had about game platforms.

Their earliest documented meeting was on March 30, 1999 (28 days after the PS 2 announcement), in conference room No. 2095 of Building 5 on the sprawling Microsoft campus. There were Jelly Bellies, and Blackley kept picking out the red ones to eat. They brainstormed things such as how to get a PC to boot extremely fast, a project they would undertake as a demo to wow Bill Gates. Berkes recruited Colin McCartney and Drew Bliss to create such a demo.

Microsoft needed a real reason to attract game developers. It had the PC game market, but that wasn’t so alluring to a lot of developers, who saw it as a shovelware market, where publishers dumped a lot of second-rate titles and piracy was a big problem. Blackley, Bachus, and others saw a chance to appeal to the creative side of game development. They would clear the business obstacles out of the way so that game designers could be artists. As with other art forms, games were going beyond their beginnings. They wanted to make games cool, not nerdy. It was a mission to gain both business and cultural acceptance.

“We gave a lot of time to talking about that,” Blackley said. “It was part of a larger trend that made games acceptable and respectable in the larger, broader audiences. In that respect, we were trying to do good.”

Berkes saw this new game machine as a “PC imbued with the attributes of a console.” Inside Microsoft, they embraced the Japanese concept of “ringi,” or getting a consensus among colleagues without sacrificing the power of the original idea. They recruited Nat Brown, a seasoned Windows manager who regularly ate lunch with Bill Gates’ assistant. Berkes said Brown came up with the name Xbox, though he didn’t stay for a long time on the project and others didn’t remember who exactly had named the machine.

Blackley recruited his buddy Rob Wyatt, a graphics expert who had worked on the Trespasser game. Nvidia’s Dave Kirk was one of the first outsiders to hear about the machine, which would require a screaming fast graphics chip — the kind of thing that Nvidia made. Intel’s Jason Rubinstein, a game evangelist, and Ned Finkle of chip maker Advanced Micro Devices, also got wind of the plans.

Luckily, Microsoft had a hardware group with engineers who were skilled at making computer mice, joysticks, keyboards and other peripherals. Gates let the hardware division survive within the software giant because it made money. Rick Thompson, a tough New Yorker, ran the business on razor-thin margins, always aware that it would be shut down if it lost money. He was brought into the Xbox discussions, as his group might be tasked with building a console, if Microsoft chose to go it alone without hardware partners.

Microsoft had also acquired a large hardware engineering team in Silicon Valley when it purchased WebTV for $425 million. The acquisition gave Microsoft its first real hardware appliance for the home, a stripped-down computer meant for browsing the web on a dial-up modem. Craig Mundie, a Microsoft executive who was responsible for the acquisition, had the ear of Gates and wanted WebTV to lead the game console effort. Many WebTV veterans had worked at 3DO, and they favored the console approach.

But the four musketeers saw things differently. Berkes and Hase in particular saw the strengths of the PC. You could change the hardware and upgrade software for it every year. It used cheap, off-the-shelf parts made by the tens of millions. It had a much easier architecture and programming model than the proprietary game consoles. The musketeers didn’t see eye-to-eye with the WebTV crew, which wanted to start from an appliance and move upward into a console. Instead, they wanted to start with a PC and move down from there.

They gathered their allies along the way. Ed Fries, the head of Microsoft Game Studios, turned out to be the fifth musketeer. The business wouldn’t have gotten off the ground at all if he hadn’t believed in it. After all, someone had to make games for the machine, and Fries was the one who held the purse strings for making PC games at Microsoft.

Fries joined Microsoft as an intern in 1985 and had worked successfully on Office. In 1995, he moved over to resuscitate Microsoft’s moribund game business. His Age of Empires success gave him real credibility with Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer. Fries had self-financed Microsoft’s quick expansion in game development, and now he was keen on expanding even more with the Xbox. He had considerable credibility with the Microsoft brass.

“They had a plan I believed in,” Fries said of the Xbox team.

The beauty contest

The Xbox guys wanted their console to be a Ferrari, with a hard disk drive and the best PC graphics components. But the WebTV crew wanted a true appliance that had nothing to do with the PC. It would be cheap and capable.

Bill Gates had to settle the matter of who would lead the project. The WebTV team, led by people such as Nick Baker, Dave Riola, Steve Perlman, Tim Bucher and their sponsor Craig Mundie, argued that the appliance was the way to go because of its low costs. The WebTV crew focused on the $300 cost that most consoles sold at. They huddled together with Mundie’s Windows CE low-cost software team. John DeVaan, another executive in charge of WebTV, carried weight with the Microsoft inner circle.

The question was who brought the biggest guns to the table. The two sides met with Gates for a “beauty contest” on May 5, 1999. All told, more than 20 people were in the room. Fries was an advocate for the hard disk drive, which he felt was key to graphics quality and a differentiator for the machine. He knew it cost a lot but was frustrated that the engineers couldn’t design a more cost-effective box. He spoke up and believed that the hard drive would fundamentally enable online gaming and set Microsoft apart from the rivals. Gates favored this argument.

Gates asked how easy it would be to convert games from the PC to the Xbox. Blackley said it would be easy because they shared a common DirectX heritage. The Xbox team said the machine would be compatible with the Windows PC, mainly because they believed that’s what Gates wanted to hear. The WebTV people didn’t have a similar good solution for software, as they were dependent on Windows CE, a stripped-down version of Windows that wasn’t compatible with the latest version of DirectX.

As Blackley watched Gates, he was impressed that Gates “ran a no-bullshit operation.” Gates reminded Blackley of J. Robert Oppenheimer, one of the fathers of the atom bomb, who was hardcore, fierce, but also kind. He had no patience for those who didn’t do their homework. The WebTV guys scored some points, noting that the Xbox bill of materials was completely unrealistic.

“This machine had to surprise and delight consumers,” Blackley recalled later. “If you hobble its ability to do that by being too clever with the bill of materials, you won’t get people to clamor for it. The greatness has to be in the machine before it becomes indispensable to the consumer. People will buy it not because it is cheap, but because it is great.”

The WebTV crew also believed they could create a custom graphics chip that could be used across a range of different home devices. But the Xbox team wanted to use high-end PC parts so they could get into the market much faster. They planned to outrun the consoles by updating the hardware every two years. The WebTV team made the mistake of relying upon Windows CE as its game operating system. Gates knew it couldn’t run games well.

Gates said he would love to attack Sony from both fronts, but he didn’t think Microsoft could execute on two different plans. Essentially, the Xbox team brought more heavy weapons to the fight, and Gates sided with them because it made sense to start where the company was strongest, with PC technology and PC content creation tools. But Gates didn’t kill off the WebTV side entirely, as that group had the hardware engineering expertise that was missing elsewhere in Microsoft. The WebTV group later played a small and temporary role in the first Xbox launch.

“Bill was willing to try doing something big and risky and cool,” Berkes said recently. “It was an amazing time.”

Convincing outsiders to support Xbox

After getting the go-ahead, the Xbox team started to seek outside input from developers such as Tim Sweeney, the graphics wizard at Epic Games, maker of Unreal.

Blackley, as a former technical game developer, was a real asset in communicating with the best of the game development community. He explained Microsoft was going after the 29 million hardcore gamers who spent most of the money on games. Kevin Bachus (pictured right) filled knowledge gaps, so the two of them could be pretty persuasive in a meeting.

A big part of Microsoft’s message was that it could provide a counterbalance in the market to Sony’s growing dominance and provide an alternative platform for independent publishers and developers, Bachus said. Microsoft could come into this market and be welcomed as a savior, not as a monopolistic devourer. Microsoft’s entry into the market also helped further legitimize the game industry as a grown-up market, not just a narrow niche for kids. The company could intersect the game industry at a critical point in its transition to mass media.

“The existing consoles were hardware-centric,” Berkes said. “Here’s a chunk of hardware, now go figure out how to write some games. The existing software tools and development environments were primitive at best. A key principle behind the Xbox was to put the developer and content creation first.”

Sony felt like it was in close touch with established developers, said Molly Smith, a former Sony spokeswoman who watched the Xbox story unfold from a competitive view. After all, third-party publishers created 70 percent of the games on Sony’s consoles. But Microsoft’s pitch struck a chord with PC developers, indies, and those that wanted to break into consoles.

Bachus focused on the non-technical sides of the project. He crafted the first profit-and-loss proposal and helped figure how to relate to game developers and publishers. He worked on the message about what Xbox should represent and communicate that both internally and externally. The aim was to show outsiders that Xbox was easier to develop for.

“There was incredible internal and external resistance and skepticism about Microsoft making a console,” said Drew Angeloff, who would join Blackley’s entourage in the early days.

Microsoft’s team tried to find a PC maker to create the Xbox hardware, while Microsoft focused on the software. Leaders like Michael Dell turned them down flat, as they saw no profit margin in a “razor and razor blades” model, where you sold hardware at a loss and made money on the games.

It was becoming evident Microsoft might have to make the machine itself, marrying the best of the versatile PC with the best of appliance-like game consoles. Intel’s Pat Gelsinger told the team that the Xbox would cost a lot more to make than Microsoft thought, and Intel decided to ratchet down its participation.

“We laughed at the idea they would blow a few billion dollars,” said one Intel source.

Inside Microsoft, it was sometimes hard to get people to join the team, which some had deemed career suicide. Blackley said others referred to the Xbox as the “coffin box,” because it was going to be dead on arrival. But Blackley felt like he had nothing to lose. He had no valuable stock options, in contrast to early Microsoft employees. He didn’t have much to lose.

The team pressed on. They felt the Xbox could be a classic disruptive technology, allowing a new entrant to enter games and undercut the existing way of doing business. The Xbox would be the way for developers to express themselves as true artists.

A growing team, with ruffled feathers

With official approval, Rick Thompson got drafted to be the boss. He kept saying he “wasn’t big enough for this job.” Under threat of a mean-looking Steve Ballmer, who had the habit of smacking a baseball bat into his palm during serious meetings, Thompson reluctantly agreed to head the business as general manager. Robbie Bach became the executive who owned the business, supervising Thompson.

With official approval, Rick Thompson got drafted to be the boss. He kept saying he “wasn’t big enough for this job.” Under threat of a mean-looking Steve Ballmer, who had the habit of smacking a baseball bat into his palm during serious meetings, Thompson reluctantly agreed to head the business as general manager. Robbie Bach became the executive who owned the business, supervising Thompson.

The team had strong personalities who had the “ego to put up with any amount of criticism and make people believe in the project,” Drew Angeloff said, as well as “the smarts to create a compelling pitch, turn that pitch into a strategy and tactics, and execute.”

As Xbox gathered steam, it became as fun as working for a startup. Bachus said, “Without question, the most memorable part of my Xbox experience, personally, was the fantastic team I got to work with (and help to build). Every memory I have of that time has much, much more to do with personal interactions – with my three fellow original “instigators.”

Nat Brown helped recruit J Allard, who had shipped a lot of products and was the Young Turk who convinced Bill Gates to get excited about the internet. When Allard and his buddy Cameron Ferroni arrived, they had the ear and respect of Rick Thompson, the general manager.

But as the team grew, some members weren’t comfortable with the loss of control that came with it. Hase and Berkes (pictured right) dropped out of the project, returning to their day jobs, as the project morphed beyond their original vision.

Berkes had originally hoped the machine would be more like a PC than a console, where it was profitable on its own merits. But as time passed, the Xbox model morphed into a pure console model, where the machine sold for a low price, losing money on hardware and making it up in later years via cost reductions and game sales.

“The concept we originally envisioned was designed to be profitable and to disrupt the traditional razor and razor blades game console model,” Berkes said. “Obviously the business approach deviated significantly.”

Brown, who felt quite comfortable handing off a project because he had done so before, decided to take a leave of absence from Microsoft. But upon joining, Allard had to smooth things over with Blackley, who also didn’t like losing control of the project and didn’t get along with Thompson. One of the things that Thompson held against Blackley was that vendors who were brought in by the Xbox team were starting to get unpredictable, charging higher prices than they had initially proposed for components. That wasn’t exactly fair, as the vendors curried favor with low quotes and then switched their bids to more realistic pricing. Still, it hurt the credibility of the Xbox founders, who had secured those initial quotes in the first place. Blackley and Bachus found they had to carve out new roles. They both agreed to stick it out.

“Part of it was Trespasser,” Blackley recalled, even as he felt some grief about the hijacking of the Xbox. “I was not going to fail again. I decided I could react to Trespasser by making it make me stronger or weaker.”

Making the team

J Allard was installed as the project manager under Thompson, tasked with the technical job of making the Xbox happen. At first Allard (pictured right) was skeptical of a Windows-based “eMachines for games” PC.

But as he returned to his childhood love of video games, he got excited about the challenge. Steve Ballmer challenged Allard to “build another Microsoft in entertainment.” Allard then brought in the “FOJ, or friends of J,” such as Jeff Henshaw. Thompson recruited hardware executive Todd Holmdahl, who ran the mouse division, as the hardware integration chief.

Blackley came to understand that Allard had credibility with the top brass, while Allard understood Blackley’s technical expertise and game knowledge. Blackley ultimately headed a team called the Advanced Technology Group.

The technical team included experts like Rob Wyatt, Mike Sartain and Mike Abrash. They had the job of defining what the Xbox would be, to create cool things that showed developers the potential of the Xbox was, and to interface with game developers on technical matters. Blackley came to relish the role, as it put him in touch with the most important game developers around the world. He was the ideal missionary because of his own roots in technical game development.

Drew Angeloff, who joined Microsoft’s ATG and handled a bunch of tasks related to building demo machines and tools, remembers the time as a specially rewarding one, with a passionate team and a far-reaching goal.

Bachus acted for a short while as a product planner, but ultimately built and ran a third-party developer relations team that was responsible for attracting game publisher support for the Xbox and then overseeing the development of games for the Xbox. He had to build a team of account managers who held the hands of publishers and guided them through the capabilities of the new console. As much as he could, Bachus exploited the fact that developers had a hard time working with either Sony or Nintendo. In one three-week period, Bachus and Blackley visited 40 game publishers and developers.

New arrivals came by the day. David Hufford signed on as the first public relations guy and started building a team of “storytellers.” Horace Luke joined to create the industrial design for the Xbox. It was such a diverse group that Allard said, “These guys would never accidentally meet by walking into a bar.”

Blackley said, “It was a cast of characters. Microsoft had the full spectrum of wackos in the best way.”

Making a real business

When you’re starting a billion-dollar business inside a company like Microsoft, it can feel like a startup. But everybody involved had to do their jobs at 100 miles per hour, Blackley said.

When you’re starting a billion-dollar business inside a company like Microsoft, it can feel like a startup. But everybody involved had to do their jobs at 100 miles per hour, Blackley said.

“If one person wasn’t delivering what they were supposed to, it had a huge impact,” Blackley said. “I don’t think people appreciate that in that first year, it was not a foregone conclusion.”

From the beginning, Robbie Bach’s contribution was organizational. Bach (right) had led successful teams in the famous Microsoft Office suite wars that saw the company dominate the office productivity suite market. No matter what the competitive challenge, Bach’s teams almost never lost.

Now his job was to “orchestrate the teams so that they worked together to create a great Xbox ecosystem.” He had to oversee everything from strategy development to relationships with key retailers and publishers.

The challenges kept getting bigger and bigger. After lining up support within the company, the team had to go out and find hardware partners, game publishers, and developers to support the mission.

“It’s one thing to come up with the capital to build a console,” said Drew Angeloff. “I think there are actually a lot of potential big players who could build a console. However, very few of these players would be comfortable with the risk of starting a such a huge endeavor. Also I’m not sure how many big players would be willing to sign up to take on fierce and brilliant competitors like Sony and Nintendo.”

Microsoft certainly had the cash to carry on a fight with Nintendo and Sony. Rick Thompson tried his best to go shopping. He asked if Nintendo, Sega, Electronic Arts or others would agree to be acquired by Microsoft as a way of jumpstarting its Xbox game portfolio. But that was a very expensive way to get into the business, and ultimately Steve Ballmer pressed the Xbox team to figure out an organic path to profitability. Thompson got more and more worried. The clock was ticking away for a launch in the fall of 2000.

Bait and switch on Bill Gates

Allard and Ferroni took charge of creating the operating system for the Xbox. They started with Windows and started tossing things out that a game box didn’t need. Finally, they came to a grave conclusion and went to Bill Gates.

Allard and operating system expert Jon Thomason told Gates that the box wouldn’t run Windows. It was too clunky and the Xbox operating system had to be streamlined to run games at the fastest possible speeds. Gates hated the idea, but relented. It more or less became a DirectX operating system. So much for the sacred cow at Microsoft.

“I think that was the closest Bill ever got to strangling me,” Allard said.

Gates had originally favored the Xbox group because it supported Windows. Now he had been hoodwinked, as the team was taking Windows out of the Xbox.

“I guess you could say we did a bait and switch,” Nat Brown said.

The Xbox started to take shape in other ways too. Fries believed that one of the best decisions was when Bach decided not to put a standard dial-up modem and instead make the box into an Ethernet-only high-speed internet device. That was another decision that Gates hated at first. But making the box broadband-only would raise the bar for developers and online gaming. Also, removing the modem knocked out $5.18 per box. That added up to $221 million in savings if the machine sold 43 million units.

“This was very controversial at the time and was clearly the correct decision in retrospect,” Ed Fries said recently.

Arguments went back and forth about the hard drive. Developers loved it, but its cost could never be cut to less than $50 over the life of the product. The team knew it would be the main reason for the machine’s cost overruns. As the decisions got made, the fall of 1999 came and went without any announcement from Microsoft.

On a design basis, Drew Angeloff looks back on the decision to put the power supply in the box rather than in the cable as a big mistake. Including the power supply made the box much bigger, with a gigantic fan to go with it that took up a huge amount of available space.

That doomed the industrial designed to be a huge, VCR-sized box. Horace Luke had trouble with the size, but he started sketching and molding away at prototypes.

Looking at research, Luke decided, “Green is the signature color of technology ever since the beginning of time.” That’s a nice cover story, Blackley recalled, but he really believed Luke used green because it was the only one he had handy. Other people had stolen his other color markers.

Fortunately, Sony, Nintendo and Sega had all avoided green for some reason. Luke visited dozens of homes to see how people used game consoles in their homes and where they put them. He made sure that the Xbox cables were nine feet long — longer than the other consoles’ cables — because that way players could sit on couches that were far from their TV screens.

He settled on a rectangle design with a big X emblazoned in the middle. In arguments with Luke over expensive design elements, Blackley said, “We needed to learn that cool was just as important as cost.” Luke finally stuck a glowing green orb, a jewel that exuded “nuclear energy,” at the center of the X.

Eventually, Luke learned he had to design a fake box that was the “show box,” or one that was meant to be taken on the road to impress supporters. This one would be a chrome box in the shape of an X. Later on, Luke’s hands would turn black as he polished the chrome on the show box.

Hail Mary

Rick Thompson (pictured right) never quite believed that the numbers would work. He opposed the hard drive, but had to accept it.

Rick Thompson (pictured right) never quite believed that the numbers would work. He opposed the hard drive, but had to accept it.

Thompson figured the company needed to spend more than $1 billion before it saw a dime of revenue. In a slide presentation entitled “Hail Mary,” Thompson showed Gates the grim numbers on Dec. 21, 1999, when there were about 60 people working on the Xbox.

“If you do this,” Thompson said in a presentation to Gates. “You will lose $900 million over eight years.”

“Can’t you do better than that?” Gates complained. It got worse. If Microsoft were forced to match Sony in a price war, Microsoft would lose $3.3 billion. Revenue from online gaming became a wild card. No one knew if it would take off or if a proposed service that Allard was working on, Xbox Live, would ever work.

Robbie Bach said, “This is a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle on a good day.” Thompson made more rounds to game publishers, checking to see if companies such as Japan’s Square would agree to be acquired. But the Square executives wanted to sell 40 percent of the company for more than $2.5 billion.

“It was a laughable price,” Thompson said.

Still, Microsoft had the cash. It was generating $1.5 billion in cash every month from its Windows and Office businesses. Microsoft had $30 billion in cash, while Sony had $5 billion and Nintendo had $7 billion. Even with all that money, Ed Fries wanted to grow the game business more organically, and Bill Gates eventually agreed that was the way they would go.

The Valentines Day Massacre

Unfortunately, journalists were sniffing around and they got wind of the Xbox.

Tom Russo, a senior editor at Next Generation magazine, got hold of a rumor and confirmed it with the help of his boss Chris Charla. They ran a story about the project. I followed with a story in the Wall Street Journal on how Microsoft planned to spend billions on the project.

When Sony officials read about it, they finally had a handle on how serious Microsoft was about the video game market. Before that, it was really unclear whether Microsoft was committed, said Molly Smith, former head of corporate communications for Sony’s U.S. game division.

“I wouldn’t say we were dismissive,” Smith said. “But we were puzzled. There were plenty of projects like tablet computers that came out of Microsoft but never really went anywhere.”

Ed Fries (pictured right), the former game studios chief, still has vivid memories of the “St. Valentines Day massacre” in February, 2000. That was the name for an all-day meeting at Microsoft that went into the evening. Bill Gates started out asking why they were getting into this crazy business and it went downhill from there. The meeting was part of the final review for the team and whether Microsoft would go forward or not.

Rick Thompson, who was the general manager at the time, recalled, “We looked around at the table and asked if we really wanted to lose billions of dollars over eight years.”

Fries had to explain his plan for developing the Xbox games with a divided staff, with half the developers focused on PC games and half focused on the Xbox. J Allard was impatient with Thompson and said, “We have to stop fucking around.” Allard wanted to move forward and keep the rest of the company out of his way. Gates asked for explanations of the dozens of decisions the team had made. Some of them were quite technical, like Cam Ferroni’s view that games should access the kernel, or the lowest level of the operating system, so they could operate with the utmost speed.

Steve Ballmer said, “If we do this, we don’t ever revisit this decision. We support these guys.”

As the meeting closed, everyone was exhausted. Everybody had to step out of the meeting and tell their wives that they wouldn’t be home for Valentine’s Day dinner. The meeting because known as the St. Valentines Day Massacre because it slaughtered a romantic evening with spouses. But in the end, the Xbox, with its glowing green orb, got the green light.

Bachus, Blackley and others had to line up demos for the announcement, so they hit the road again to pitch publishers around the globe. Fries had to get moving. He had 400 game developers at 10 internal studios and relations with 20 outside studios. They had to get focused on making games for the Xbox. The creative talent needed a considerable amount of time and freedom to cook great stuff.

At one point, Gates asked Fries, “Do we need those cute mascots? Do we have any?” Fries considered buying Midway Games, a struggling game publisher, but Fries didn’t feel like there were many assets to be gained. Still, he knew he had to at least double the size of his game studios to pull it off.

Chip shootout

Just after the approval meeting, Newsweek ran a fascinating cover story about the “Amazing PlayStation 2” and how it would change gaming technology forever. It was about how Sony wanted the box to be so much more than a game machine, and it was the manifestation of Microsoft’s worst fears. The PS 2 was going to let gamers “jack into the Matrix,” claimed Ken Kutaragi, head of Sony’s PlayStation business. It was going to be a “digital delivery system” for Sony games, software, tunes and services. It was a convergence play.

Microsoft, by contrast, had decided to focus on games, games, games. It too wanted to head Sony off from being the gateway to home entertainment, but the way to do that was through better games, Blackley said.

That meant that the final hardware for running the games was critical. Choosing the final graphics chip was a vital decision, but one that was dragging out. Jen-Hsun Huang (pictured below), chief executive of Nvidia, wanted the big deal, which could be a huge boon for his graphics chip business. But he didn’t want to sell Microsoft chips at a loss.

Game developers like Wyatt insisted on using Nvidia because developers were so familiar with making games for it. But Nvidia’s price quotes were much higher than what others offered. Rick Thompson felt like he had been sold a bill of goods, and it took Blackley and Bachus and others a lot of effort to keep Nvidia in the bidding. The nuances of chip economics were new to Microsoft. The price depended on the size of chip, its yield, complexity of design, and ability to be manufactured all came into play.

“I wanted to do the deal, but not if it was going to kill the company,” Huang said.

“I wanted to do the deal, but not if it was going to kill the company,” Huang said.

Thompson started to favor a pitch that came from the WebTV team, which wanted to get back into the project. Team members had unearthed graphics chip design house GigaPixel, which promised to design a brand-new graphics chip with WebTV’s engineering help. Thompson believed that if Microsoft owned the chip it created, it could save a huge margin and control its own destiny at the same time.

Thompson chose to move ahead with GigaPixel. George Haber, head of GigaPixel, was delighted. Microsoft would invest $10 million in GigaPixel and pay $15 million to help develop its chip. If GigaPixel later went public, Microsoft would make so much money on the investment it would essentially get its graphics chips for free.

Haber got a call from Nvidia’s Huang, who hinted in not so polite language that if he did the deal, Haber would be beholden to Microsoft for life. But Haber went ahead. Gigapixel moved its 33 employees into the WebTV building in Mountain View, Calif., and Haber gently taunted Huang — a conversation he would later come to regret.

Within the Advanced Technologies Group, there was dismay. To them, GigaPixel was nothing but a bunch of promises.

“This was the worst decision in the entire project,” Rob Wyatt (pictured right) recalled. “Remember, this chip didn’t exist, the proposed architecture was new, and different from their prior design. We never got a working version of that. This was when programmable graphics shaders were coming out and GigaPixel had never made a programmable chip. We knew the box would fail if it used this hardware.”

“This was the worst decision in the entire project,” Rob Wyatt (pictured right) recalled. “Remember, this chip didn’t exist, the proposed architecture was new, and different from their prior design. We never got a working version of that. This was when programmable graphics shaders were coming out and GigaPixel had never made a programmable chip. We knew the box would fail if it used this hardware.”

The ATG team fought to keep Nvidia alive. The chip schedule pushed the launch date into 2001. Chip makers often needed two years to make chips. But Microsoft was pushing a schedule that would give chip vendors a little more than a year to do their work. Wyatt argued so much that he eventually got fired.

The Xbox was originally scheduled to be launched at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, 2000. But the team pushed that back to March. The extra time before the announcement gave Thompson a last chance to revisit his deals. He tried to buy Nintendo again, but balked at the $25 billion price and the Nintendo executives didn’t want to sell anyway. Microsoft’s proposal was to have Microsoft provide the hardware for Nintendo, which would focus only on making software. To Nintendo, this seemed ludicrous, since Microsoft had never made hardware before.

Meanwhile, some engineers proposed creating a companion handheld, the Xboy. But Bach nixed the idea, saying he had to keep his eye focused on the console business. Blackley, meanwhile, lined up some cool demos from Pipeworks and the animation house Blur Studio to create “eye candy” demos for the Xbox unveiling. When Blackley saw Blur’s work, he called them up and said, “This is fucking great!” He was all set for the unveiling at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco in March, 2000.

At the very last minute, just before the announcement, Nvidia got back in the game with a new proposal to fuse two chips together. Word leaked out about GigaPixel and the game developers, convinced that the console wouldn’t work as well with a new chip as it would with the Nvidia hardware they were familiar with, revolted. So Microsoft and Nvidia finally signed a deal. Microsoft would pay up to $48 a chip for the first 5 million chips and would also pay Nvidia $200 million in an upfront fee. Thompson visited Gigapixel at WebTV the next day and announced, “We signed a deal with Nvidia last night.” Haber and the employees were stunned.

“If we hadn’t caused such a stink, we wouldn’t be talking today,” Wyatt said a decade later. “Nvidia had their own issues, but they had a working chip and were willing to work within our limits and redesign it to make it work.”

Similarly, Advanced Micro Devices thought it had a deal clinched to provide the microprocessor for the Xbox. That was true until the night before the announcement. Paul Otellini, one of the top executives at Intel, convinced Bill Gates that Intel could provide the chips. Intel clinched the deal and the AMD employees were dumbfounded when they heard the news at the announcement.

The GDC Unveiling

At the Game Developers Conference, the Xbox was an open secret. Bill Gates was giving a keynote before 5,000 developers and referred to the mystery box under the black cloth as a “very deep secret,” getting chuckles from the crowd. He teased the audience and finally announced the Xbox, unveiling Horace Luke’s chrome “show box.” Blackley came out on stage and ran the demos. Everything went smoothly.

At the Game Developers Conference, the Xbox was an open secret. Bill Gates was giving a keynote before 5,000 developers and referred to the mystery box under the black cloth as a “very deep secret,” getting chuckles from the crowd. He teased the audience and finally announced the Xbox, unveiling Horace Luke’s chrome “show box.” Blackley came out on stage and ran the demos. Everything went smoothly.

Game developers loved the fact that the machine had an Ethernet port and a hard drive, opening up great possibilities.

“The future of entertainment was right there in every box,” David Hufford, the PR guy, said recently. “The Ethernet port and the hard drive. Those features said the future will be open. It will be social. It will be digital. It will be more than games.”

Microsoft won over developers in part by asking them what they wanted, and then actually listening to what they said. Microsoft was dreaming big and it wanted to partner with the greatest minds in gaming to bring their ideas to life.

“We made it uncool for platform manufacturers to ship sub-par developer tools and support, forever,” said Drew Angeloff.

As an example, Microsoft didn’t try to create its own development system with its own compilers and adapters. Rather, it extended its own Visual Studio tool from the PC, enabling developers to take advantage of the thousands of hours that had already gone into learning and refining this tool.

Chris Prince, a member of the Advanced Technology Group, recalled that the Advanced Technologies Group figured out how to create a tool called PIX, or Performance Investigator for Xbox. PIX allowed a developer to have an unheard of level of introspection into why a part of the game was or wasn’t working. They could pause the game, focus on something as small as a pixel, and see the entire sequence of computations that led to the pixel showing up on the screen at that particular time. No one else had created such a tool.

The Elevator

That night, the team partied, with many gathering at Scott’s Seafood in San Jose, Calif. The team ordered champagne. Nearby, developers from Ensemble Studios started a chant, “Xbox! Xbox! Xbox!” and pounded the tables. The headwaiter was fuming as most of the restaurant goers began doing the same thing. Jeff Henshaw went around from table to table apologizing to other guests, asking if he could pick up their tabs if they were annoyed. He paid for about 10 dinners.

After the dinner, Drew Angeloff suggested they all pile into the elevator. Blackley was the last to pile in. As he jumped in, the elevator was already sinking. Angeloff thought Blackley would get decapitated. Then the elevator dropped and slid almost four floors. It stopped halfway between floors and the occupants had to pry the door open. Horace Luke, the designer, was shouting, “My leg, my leg!” (He turned out to be okay.) Kevin Bachus said later that he had counted 24 people in the elevator. Half the team wanted to run, while half wanted to stick around and tell somebody what had happened.

“You could tell who grew up in bad neighborhoods,” Blackley said.

The day after it happened, I asked Blackley about the elevator incident. He said, “A team that doesn’t have fun can’t make a fun product.” Blackley’s father called him up to congratulate him when the story ran in the Wall Street Journal. Around that time, I started thinking that this story had the potential to be a book. Robbie Bach shuddered when he read the story in the newspaper and told the instigators, “Remember, you guys are representing Microsoft.”

A little game called Halo

Even though the console was now on track to launch, Rick Thompson, who had tried to believe in the business, finally decided to give up. Too many deals failed to come through and he was worried about the profitability of the venture. “I said we were not on the right path,” Thompson said. “I said it 50 times. I was consistent all the way. Only by some miracle in the business model could I see us making money sooner.”

He resigned as general manager and Robbie Bach took over as “chief Xbox officer.” The process of greenlighting games began, with a fabled “Star Chamber” voting yay or nay on proposals.

The camaraderie continued. In a prototyping lab with a lot of dangerous equipment, Rob Wyatt yelled at Drew Angeloff, “Get away from me with that blowtorch, you skinhead.” The quote made it into Time magazine as a reporter was visiting at the time.

And Nvidia wound up buying Gigapixel, netting the spurned George Haber $37 million as part of a $186 million stock deal.

The Xbox team expanded dramatically, growing to 1,000 employees through the summer of 2000. Another 5,000 to 6,000 third-party developers were working on games. Microsoft was winning the hearts and minds of the industry. Electronic Arts CEO Larry Probst said privately he would welcome Microsoft, as it made him less dependent on Sony.

Ed Fries had been busy getting dozens of games ready for the Xbox launch. But no one knew exactly what the killer app would be. Luckily, a planner named John Kimmich had been scouting developers and came upon Bungie, which was on the verge of something big. He visited Bungie in Chicago along with studio executive Stuart Moulder.

On June 19, 2000, Ed Fries announced that Microsoft was buying Bungie, which was working on a promising title called Halo. Bungie had never sold more than 200,000 units of a game, but it was considered a star Mac developer. Microsoft was able to pick it up for about $30 million. It was the bargain of the century. The full staff relocated to Redmond.

But first, Fries had to take a phone call from an irate Steve Jobs, who raged about how Microsoft had just raided the best developer of games for the Mac. To mollify Jobs, Fries had to appear at a Jobs keynote speech and promise support by making Mac games.

Jason Jones (pictured above), the technical lead on Halo, was excited about adapting the first-person shooter game from the PC to the Xbox. His team focused closely on mapping the shooter controls to a game controller’s buttons, and figured out how to assist the user’s aim with a little automated nudge in the right direction. The small team had barely 10 months to get the game ready for a fall 2001 launch. That was now the appointed time for the launch of Microsoft’s first game console. They wanted to do a game that couldn’t be done on any other console.

Meanwhile, the team gained more expertise. After seeing a demo from Bachus and Blackley, Brian Schmidt joined the Xbox team as an audio expert. His mission was to integrate Dolby Digital 5.1 surround sound into the Xbox. Digital surround sound hadn’t been done before in gaming, and it wasn’t an easy process to pull it off. Negotiations between Dolby and Microsoft lasted months.

Schmidt gave a demo to Bill Gates one day as he was passing through on a tour. At the end of the day, Gates met with 200 team members in a cafeteria. Asked what was the coolest thing he saw that day, Gates mentioned the “audio stuff.” At that point, Schmidt felt the admiration of 200 pairs of eyeballs on him. Thanks to Schmidt and others, gamers would be able to listen to that pulse-pounding music and cacaphony of gunfire in Halo in surround sound.

Gathering momentum

Sony’s PlayStation 2 was gathering steam. It had launched in Japan in March, 2000, and sold more than a million units on its first weekend. It effectively killed Sega’s Dreamcast, which until that point had been a scrappy little console with potential.

Then Sony lined up a U.S. launch for October, 2000. It looked like it would be in the market for a full 20 months before Microsoft sold its first machine. Meanwhile, Nintendo was readying a console called the GameCube.

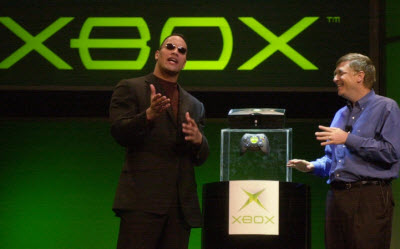

Microsoft’s planners had become hopeful that it could sell 100 million Xbox consoles over four years. But the long delays in choosing chip vendors were coming back to haunt it. Nvidia was rushing to get its graphics chips done on time, and contract manufacturer Flextronics was scrambling to get its assembly line in place. Everything was coming down to the wire. At the Consumer Electronics Show in 2001, Bill Gates and Seamus Blackley showed off the real Xbox design, a black box with an X and a green orb in the middle. The wrestling champ “The Rock” came out on stage, helping make the Xbox seem cool. The crowd loved it when, in good humor, The Rock verbally put down Bill Gates, the richest man in the world, quipping “Nobody cares what you think, Bill.”

“One of the basic premises of the Xbox is to put power in the hands of the artists,” Blackley told the crowd.

Later, at a Gamestock event in Redmond, Ed Fries got to show off Microsoft’s first-party titles for the Xbox. Again, he emphasized how games could become a form of art.

“The thing that is happening with technology that is so exciting to me is we are finally leaving the cartoon world behind,” he said. He noted how some of the characters in the best games, like Metal Gear Solid, didn’t even have eyes. There was only so much emotion you could build into such characters.

“We have an epic battle,” Fries said. “You’ve got the world’s largest software company fighting the world’s largest consumer electronics company and arguably the world’s largest toy company, and they’re all spending billions of dollars to push this business forward.”

More than just a battle, Microsoft’s bet was that games could aspire to be more than mindless entertainment.

“A great book, a great movie, a great play — they are about more than just killing time,” he said. “We need to create art. If we take that seriously, if we focus on making art, not just entertainment, then I think for the first time we’ll deserve to speak to the mass audience and inherit our rightful place as the future of all entertainment.”

He showed off a bunch of games, closing with Halo. It was an inspiring speech, but there were some duds in the line-up that truly weren’t works of art.

A heartbreaking E3

At the E3 trade show in 2001, the big three console makers had their chance to show off their new titles to the world. Ed Fries and others had lined up scores of titles from internal and external developers. EA and other publishers were stepping forward. Big titles were coming from the likes of Lionhead Studios and Oddworld.

At the E3 trade show in 2001, the big three console makers had their chance to show off their new titles to the world. Ed Fries and others had lined up scores of titles from internal and external developers. EA and other publishers were stepping forward. Big titles were coming from the likes of Lionhead Studios and Oddworld.

Robbie Bach came out on stage at a press conference at a big Los Angeles sound stage. He announced the Xbox would debut for $299 in November, 2001. Bach tried to turn on the Xbox at the E3 presentation, only to have it fail.

“Let’s get that video up,” Bach said, referring to a feed showing the Xbox powering up. One of Blackley’s cool animated demo films didn’t run at all. On stage and at the Microsoft booth, demos didn’t work so well because the prototype Xbox machines were running at about a third of the machine’s proposed speed. Bach said that 80 Xbox titles were in the works, including 27 online games.

Years later, Bach still remembers the event as “my worst presentation ever.”

By comparison, Sony outdid Microsoft in every way. Sony announced it had sold more than 10 million PS 2s since March, 2000. Then Sony trotted out a bunch of exclusives, from Gran Turismo 3 to Metal Gear Solid 2 and a new Final Fantasy title. It was an impressive showing. Where Microsoft got developers on stage, Sony got the true artists, or company CEOs. Even Sony’s party put Microsoft’s to shame. It was a serious case of one-upmanship.

At E3, it seemed like Microsoft had brought a knife to a gunfight. Microsoft was hoping for the Battle of Midway, and instead it got hit with Pearl Harbor. When Journalist Steve Kent told a Microsoft PR person what went wrong for Microsoft at E3, the conversation lasted 90 minutes.

Just after E3, Kevin Bachus had left Microsoft. With his buddy gone, Blackley was determined to get the job done.

But it looked like the Xbox was all set to be a failure. Sherry McKenna, head of Oddworld and an ally of Microsoft’s, said, “E3 broke my heart.”

9/11

Microsoft worked to move from the hype stage through the backlash and back to being cool again.

In the run-up to the launch of the Xbox, Bach flew into New York on the morning of 9/11. The terrorist attacks took down the twin towers and disrupted travel across the nation.

Blackley was also flying that morning, and happened to be in a JetBlue plane flying over New York on 9/11, as the smoke consumed Manhattan. He was watching it unfold on CNN on the screen in front of him. The pilot diverted the plane to Buffalo, N.Y.

Overnight, the world changed. The U.S. plunged into a standstill. The market for all sorts of things, from books to air travel, dried up. In the midst of such a fear-induced recession, coming on the heels of the catastrophic dot-com crash, consumers were likely to be in no mood to buy something so trivial as a game machine. On the other hand, there was always the chance that miserable consumers would seek out entertainment as a kind of distraction or solace. For the Xbox launch, it raised a cloud of uncertainty.

Bach ended up snagging a Ford Taurus and driving across the country back to Seattle with three other Microsoft people.

“Reminded me that America is an amazing country,” Bach said.

Blackley later said, “You can think of the Xbox as research into human happiness. You don’t want those guys to stop you from doing things that make you happy.”

Little by little, the fears of 9/11 became distant, and the idea celebrating the holidays with shopping slowly came back into the forefront for consumers. Later, at the Tokyo Game Show, Blackley was stunned to see a bunch of Microsoft Xbox ads all over one of the subway lines. He became so emotional that he started crying.

The launch in Times Square

Microsoft canceled some press events, like one for European press in Tunisia. Although it was only a couple of months after 9/11, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani requested that Microsoft continue with its plan to launch the Xbox at the giant Toys ‘R Us store in Times Square.

“They wanted to showcase the city’s resilience,” said David Hufford. “That New York City was open for business and was still the business capital of the world.”

The launch was full of uncertainty. The city didn’t exactly know how to handle the crowds, and the four-story, 101,000-square-feet store was not yet open to the public.

“On top of that, we did not know whether we had a hit on our hands with Xbox,” Hufford said. “We built it, but would they come?”

J Allard stood on a street corner with white-dyed hair and a light green shirt. A kid asked him if he knew about the Xbox.

“Yeah, I do,” Allard said, explaining why the kid should buy one.

Thousands of New Yorkers flooded into Times Square, which was bathed in acid green search lights. Microsoft game them Krispy Kreme donuts with green sprinkles.

Bill Gates walked up and down the line and shook hands with all of the fans. He played a round of the fighting game Dead or Alive 3 with his wrestling buddy, The Rock. The crowd erupted in shouts of “Bill, Bill, Bill.” At midnight, Gates handed over the first Xbox to Edward Glucksman, a 20-year-old from Keansburg, N.J., who had waited 12 hours in line.

“Bill Gates is God,” Glucksman said.

A modest proposal

Robbie Bach was beaming in the store, talking about how proud he was at that moment. Blackley introduced his girlfriend, Van Burnham, to Bill Gates. Gates bantered a little and said, “You know Seamus, I think she could help you get your act together.”

“You think so?” Blackley said. “Something has to.”

“You ought to marry her,” Gates said.

Blackley replied, “You think so?”

“Yeah, absolutely,” Gates said. “Here’s ring.”

Gates handed Blackley a ring with a square-shaped diamond and a couple of baguettes on each side.

Blackley got down on one knee and proposed. Burnham said yes. They kissed. John Eyler, the CEO of Toys ‘R Us, handed Burnham a giant stuffed unicorn as a gift.

Looking back, Blackley said, “If you are going to make a big bet in life, why not double down? What are the two biggest things you can do in life? I thought it was time to go big or go home.”

The first season

At the Consumer Electronics Show in 2002, Robbie Bach proudly announced that Microsoft had hit its target of selling 1.5 million units in its first season in the U.S. market. It was enough to give Microsoft a foothold in the market.

Halo, the sci-fi shooting game from Bungie, turned out to be the smash hit on the Xbox. Fans fell for Master Chief (pictured right) and Bungie’s masterful work of art, which had everything from haunting, pulse-pounding music to stunningly beautiful scenes and breathtaking combat.

More launches would follow. Microsoft eventually surpassed Nintendo, taking second place in the console generation. But for every machine that Microsoft sold at $299 at the outset, it was losing about $126, thanks to the $425 cost of the machine. The losses mounted as Microsoft sold more machines; it had to match Sony’s price cuts along the way, but could never cost reduce the machine enough to make money on hardware alone. And it was just too hard to sell enough games to make up for the hardware losses.

Sony had the last laugh. Before Microsoft sold its first Xbox, Sony had sold more than 20 million PS 2s. Microsoft would have to wait for its second generation machine, the Xbox 360, before it could have a shot at taking down Sony. Microsoft was never able to catch up in the first generation.

“Xbox One was cool,” Blackley said. “Perhaps not as decisively innovative as Microsoft would have hoped. But it is a great example of Microsoft taking an entrepreneurial bet.”

Read part 2 of VentureBeat’s history of the Xbox: Microsoft’s journey to the next generation

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More