Editor's note: I learned a lot from Thomas' well-researched piece. Who knew Gap ads could be so insidious? -James

"In-game ads enhance realism." Message boards, podcasts, and editorials constantly reinforce this idea. The statement has become a mantra that gamers of all stripes have repeated for over six years — but it didn’t come from a journalist or a gamer on a message board. One of the most powerful companies in modern gaming coined this phrase: I'm talking about Massive Incorporated.

The Big Bang of In-game Ads

For a long time, advertising stayed in the primordial pool of television and print media. In 2002, Everquest dominated gamers' time. Players spent thousands of hours leveling their characters in a virtual world. Some even digitally packaged the product of their endless grinding and sold it over the Internet. Everquest character auctions were some of the first organisms to move into the land of video game advertising.

When we talk about marathon gaming sessions, pooping in a sock is the first thing that comes to the minds of many gamers. To marketers, this kind of undivided attention was the advertising equivalent of a spring break party full of Scarlett Johansson look-alikes gone wild. The loss of their prized 18- to 34-year-old male demographic baffled TV and movie advertisers, and when they realized video games were a main culprit, they came running after gamers like a psychotic ex wielding a kitchen knife.

Massive Incorporated's Rise to Power

On September 30th, 2003, Massive Incorporated announced that they were going to begin focusing their company on middleware technology created by Acclaim — yes that Acclaim — that allowed developers to insert real-time ads into video games. This was the era of the Gamecube, the PlayStation 2, the Xbox, and most importantly, Xbox Live. Broadband penetration and console Internet connectivity were slowly becoming the industry standard. Advertising companies had the foresight to recognize the growing market, and Massive acquired $2.1 million in funding to begin their offensive.

Flash forward to E3 2004: Halo 2, the PlaySation Portable, the Nintendo DS, the PlayStation 3, and Twilight Princess firmly gripped the attention of the media and enthusiasts. Epic was touting Unreal Engine 3 as the ultimate middleware solution, but behind the scenes, it was Massive’s technology that would prove to be the ultimate gladiator. Massive had the developers of 10 Q4 2004 titles primed to implement in-game ads using their tech, and later that year, to no one's surprise, Atari and Ubisoft announced they would be using Massive's software. At the time, people were beginning to regard episodic gaming as an innovative way to deliver content to gamers. In reality, advertisers experienced in television promotion cooked up the idea.

In May 2006, Massive’s value reached its apex. At Microsoft’s Strategic Summit, the company announced its acquisition of Massive Incorporated for an astounding showcase-showdown bid of $250-$400 million (as reported by The Wall Street Journal). Microsoft intended to assimilate Massive’s advertising technology into Xbox Live and MSN games. With regard to monetary significance, this acquisition was enormous. To put it in perspective, the amount of money Microsoft spent on Massive is equivalent to the budget of roughly 10 to 20 high-end games. Google’s popularity was increasing, and the amount of time 18- to 34-year-old males spent on the Internet was attracting attention. The Massive buyout was a plan to tie advertisers to Microsoft’s mast and keep them from heading toward Google’s siren song. Massive Incorporated became a powerful tool that set the landscape for console Internet connectivity.

In May 2006, Massive’s value reached its apex. At Microsoft’s Strategic Summit, the company announced its acquisition of Massive Incorporated for an astounding showcase-showdown bid of $250-$400 million (as reported by The Wall Street Journal). Microsoft intended to assimilate Massive’s advertising technology into Xbox Live and MSN games. With regard to monetary significance, this acquisition was enormous. To put it in perspective, the amount of money Microsoft spent on Massive is equivalent to the budget of roughly 10 to 20 high-end games. Google’s popularity was increasing, and the amount of time 18- to 34-year-old males spent on the Internet was attracting attention. The Massive buyout was a plan to tie advertisers to Microsoft’s mast and keep them from heading toward Google’s siren song. Massive Incorporated became a powerful tool that set the landscape for console Internet connectivity.

In-game Ads Subsidize Game Development

In-game advertising cannot subsidize the entire development of a video game. Auto Assault and The Matrix Online were two of the first titles to employ Massive’s technology, and if ads alone could have sustained them, their lesson wouldn't be a glowing sign that reads “Beware: Don't make console MMOs.”

"In-game ads subsidize game development." This is a myth — a bedtime story advertisers use to scare developers and publishers in to employing their methods. If Massive’s technology could fully account for a game's development, games wouldn’t cost $60, companies wouldn't charge for downloadable content, and $100 collector’s editions wouldn’t exist. Microsoft and Massive wouldn't gloat about revenue earnings. Massive’s middleware only benefits one company: Massive Incorporated.

The Myth that In-game Ads Add Realism

The Myth that In-game Ads Add Realism

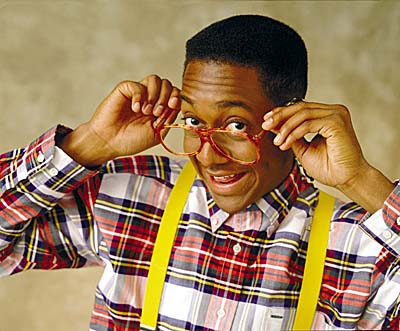

If Jaleel White’s “Did I do that?” catch phrase permanently defined his career, then “In-game ads add realism” is the sitcom one-liner that defines advertising companies. Ads do not generate realism. Good writing and well-crafted worlds do. The number of Dr. Pepper and Comp USA billboards is directly proportional to nothing more than the amount advertising you're seeing. Product placement cheapens the product; it turns game characters into virtual prostitutes through scenes crafted solely around the use of real-world items. When Alan Wake reaches for Energizer batteries, it adds nothing to the game. This scene is incongruous with the aim of gaming, which is to offer highly organic, interactive experiences. Believability in a game correlates directly to how well a developer achieves this goal, not the amount of product placement.

Mass Effect 2 is antithetical to Massive’s slogan. Bioware created an entire galaxy that feels real but isn't. The Citadel is a futuristic reality where ads are commonplace. These fabricated ads are products of a fictional universe, but they felt like they could exist in reality. This effort was a creative process — not a crutch.

In a study for Massive about gamers' perception of in-game advertising, Grant Johnson of Interpret wrote that “Gamers are open to advertising if it's done tastefully." This kind of doublespeak is exhausting. Instead of targeting individual reviewers and their personal biases, maybe we should direct that vitriol at studies like these. It's not much to point out that the advertising company spearheading the in-game ad movement paid for these studies. What other findings could they possibly come up with?

Ads Offer Zero Benefit to Consumers

Companies have every right to sell anything they want, but we have to be careful as consumers. Massive creates an economy that leverages publishers against the creative process of video game development. And it's not just Microsoft and Massive. Sony has Double Fusion and IGF. Advertising companies are the shady, unctuous car salesman of the gaming industry. They are looking to sell you a lemon.

People label motion control and casual gaming as the harbingers of death for video games, but it's the advertising companies that deserve the scarlet "A." They are an unasked-for vesitge brought over from movies and television. When a publisher pushes urban and modern settings for a game, they’re really saying, “If you want money to fund your game, change your fantasy setting to an urban environment, so we can jam ads in your game.” Sports and racing games receive disproportional support for the same reason. The only thing that is realistic about in-game ads is that they are as annoying as their real-world counterparts.

“I was playing Grand Theft Auto and I remember playing the game and seeing a billboard with a [fake] ad for 'GUP' instead of 'GAP' and I just thought, 'What if we changed that and made a real ad?” That's Mitch Davis in a 2006 statement about the acquisition of Massive. This sentiment is as fake as the nonexistent ads he's describing. Out of any possible game, who drives around Liberty City and wishes the billboards featured real properties? And in 2006, who mentions the name Grand Theft Auto without adding 3, Vice City, or San Andreas to the end of the title? Davis is using Grand Theft Auto as a buzz word. Mitch Davis doesn’t care about gamers or video games: He only cares about money.

Extra Reading

Stanford Case Study: Microsoft Acquires Massive, Inc.

The Sunday Herald: Ads in Video Games Make Millions

NPR: Video Games Serve Up Targeted Advertising

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More