GamesBeat: Clash of Clans seems kind of like that. I don’t know why it’s so popular. I’ve been stuck in the same place and trying to get through for two weeks now.

GamesBeat: Clash of Clans seems kind of like that. I don’t know why it’s so popular. I’ve been stuck in the same place and trying to get through for two weeks now.

Mahoney: There’s a lot of games like that. All the casual games that have that sort of effect, they look incredibly successful right up until the point that it stops. Then they fail badly. We’ve seen this several times in the past. You know the names.

Put it another way — your success in free-to-play, the metrics that really matter, there’s four of them. First, monthly active users, pay rate, and average revenue per paying user per month. You multiply those together to get your revenue marker. It’s easy to do. The fourth metric that matters is your longevity, your average lifetime per user, versus churn. It’s how long a person sticks around.

If you do something that alienates a user — Like, if we’re sitting here and a woman comes and offers us a double espresso and we say thanks, we’re not going to expect to see her back here for another 15 minutes. If she comes back and says, “How about something else? How about something else? You can’t actually sit here unless you’re buying something every four minutes.” They might get a little more money out of us this time, but next time you and I meet, we’re gonna sit somewhere else. A smart restaurant will say, “Hey, bug us if we need anything,” but they’re not going to bother us, so we have a good experience in their restaurant.

That’s how it works in free-to-play games as well. The mistake is — this is weird in our industry — so many game makers have gotten so fixated on monetizing rather than delivering a good game. They’re not confident in their ability to monetize. What we learned, by making that same mistake in Korea 10 years ago, is that you alienate your user base. Once you alienate your user base you have no business to monetize. It helps that we’re not really in the casual games business.

But going back to the example you raised, there’s a perfect history of casual games going like this and then dropping like this. The less you push people to monetize, the more you’re going to get out of them. That’s how it works.

GamesBeat: What are you putting a lot of emphasis on?

Mahoney: The things that matter are the free-to-play model done right — that’s the business we invented. We were the first ones to do it. We stumbled on it, we worked it for a long time, and then other people started doing it, first in the east and then in the west. That’s the best way to monetize games, when done well.

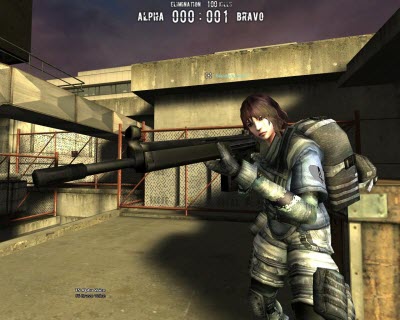

The second thing we’re focused on is immersion. We’ve done casual over the years. I’d say we’re not as good at it as some people. But we find that immersive games, games people play for years on end, are a better business. They’re also more typically the kinds of games that we want to play inside the company. We like immersive games more. Some people call it hardcore. When I think hardcore, I think hard to learn, hard to master. There are games in this industry that I love, but it took me a while to learn them. But when I think of immersive games, I think of easy to learn, hard to master. You immediately start playing and feeling like it’s easy to learn, and it progresses you very quickly in terms of your knowledge of how to play the game. We like to make immersive games, not casual games.

GamesBeat: And that can go across territories.

GamesBeat: And that can go across territories.

Mahoney: Absolutely. Immersive games are a massive market. What people talk a lot about sometimes is casual games, because there’s a whole new group of gamers who’ve never played games before. My older sister, who’s past 50 now, she plays casual games on her phone. When you get on the subway in Tokyo, you’ll see young men and women playing on their mobile devices. There’s a whole new mass of gamers.

But also, there’s a group of people like you find in Korea, and it’s really changed. You talk to 20-year-old women in Korea and they’ll say, “Yeah, I play a lot of StarCraft. I grew up playing Maple Story. Now I’m playing Sudden Attack.” And they’re really into it. You talk to them about how they’re playing games and they’re serious gamers. They’re not just messing around. In the United States — I thought Jane McGonigal’s book was really good, Reality Is Broken. She talks about something we joke about internally: the rise of the global nerd. What once was nerddom, now people just think of as a synthetic or designed flow experience. It’s why people like to play golf. I like to kiteboard. I get really into it, even if it seems esoteric for a lot of people. We know that’s a massive market. We have 80 million monthly active users around the world.

The third area we’re concentrating on is online synchronous multiplayer. That’s much more fun. Asynchronous is not really interesting from a gaming perspective or as a business.

GamesBeat: As far as acquiring companies goes, the stock market has changed a lot. Your stock price isn’t rising. What is your strategy?

Mahoney: Well, our stock price has been stuck at somewhere between 1,000 and 1,300 for a little less than a year. We went out at 1,300, so we didn’t get the same shellacking as a lot of people, but clearly the public equity markets do not trust that there’s growth in the games business. No matter how much we show it, it seems that public equity investor — If you do a peg chart, and you show growth over PEs, what you find is a flat line. It should go up and to the right, but what you find is a flat line. Most of the industry, except for one or two, are right in that flat.

Zynga is out of it a little bit. They’re actually a little bit higher because their earnings just came apart. Their PE has gone up quickly. Tencent is above it, because they’re really considered a tech company meets a platform meets a search engine meets a messaging app. They’re not really considered a game companies. But game companies around the world are all in that band.

GamesBeat: EA lost its CEO over this stock trading pattern. But they seem to have done the best they could.

Mahoney: I thought that was unfair. It’s hard. But I’d say we’re all in that band. That’s the public domain. What’s interesting is that the private company valuations are many times much, much higher. It creates a conundrum for a company that’s private, that’s growing quickly, that’s been valued over one or two rounds of capital like a private company, and then it looks to a public company to acquire it to get an exit for the venture capital guys, or it looks to go do an IPO.

We were the second-largest IPO in the world in 2011. We were 80 percent of the IPO market in Japan when we went out. We were about a week ahead of Zynga when they went out, and we were bigger than their IPO. We’ve talked to everybody. I can tell you, there’s a big disconnect between what most of the venture capital community is valuing private companies and what almost all public company investors are valuing video companies. At the same time, a lot of the buyers have left the scene.

GamesBeat: Zynga’s not buying anybody anymore.

Mahoney: And guess who else isn’t buying? EA isn’t buying. There’s a few of us left of size, but there’s not a lot of well-capitalized public companies that are ready to step up to the kind of valuations that some people would expect. We’re patient and we’re well-capitalized. If you know your business and you’re not chasing after — if you’re not out to buy revenue in the near term — you can afford to be patient. We’re not a “buy revenue” type of acquirer. We’re a strategic acquirer. Our M&A track record has been all about buying companies that will continue to grow over time and getting the right price.

When we did the Gloops acquisition in Japan, we paid somewhere between five and five and a half times EBITDA. On a forward basis, it was somewhere between four and four and a half times EBITDA. That’s a different valuation than you get from a lot of private companies.