Text adventures were some of the earliest forms of video games, but we’ve come a long way since Hunt the Wumpus and Adventure. Some of today’s surviving pockets of the genre are visual novels and gamebooks — two very niche types of games that most people associate with tons of reading. They cringe at the idea and then go peruse libraries in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim.

Despite their name, these games aren’t all about text. Interactive fiction is perhaps a better classification. That misconception can hurt sales, so manipulating the genre to emphasize its versatility and flexibility could be the key to a more successful future.

The grim state of visual novels

Xseed Games knows a little about the merits and challenges of publishing visual novels in the United States.

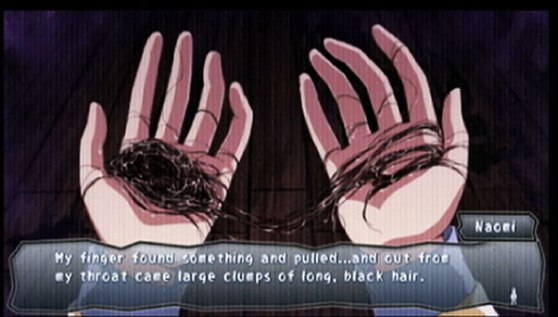

“Similar to a good book, [visual novels] can totally engross you within that world as your mind has to get creative to fill in the blanks on everything that’s happening,” Xseed and Marvelous U.S.A. executive vice president Ken Berry told GamesBeat. “This works especially well in the horror genre, something that the Japanese do very well because it’s what you can’t see that’s the most horrifying.”

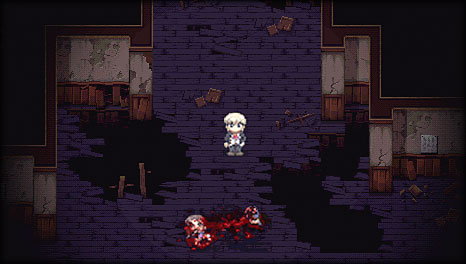

The first localized Corpse Party horror game, which released in 2011, “greatly outperformed” its sequel, Book of Shadows. Berry speculates that because the series switched from a perspective where players control an onscreen avatar to one that resembles a more traditional visual novel — with less direct interaction and player input — gamers were less interested.

Low sales forecasts have sometimes prevented Xseed from localizing more of these games, such as with Anata wo Yurusanai, which translates to “I will not forgive you.”

“It had an interesting story, branching storylines depending on player input, and the legendary [Final Fantasy composer] Nobuo Uematsu himself was in charge of the game’s music,” said Berry. The publisher passed it over because the overwhelming amount of translation work well exceeded what Xseed predicted it would make off the game.

How can companies alleviate these Western-specific problems?

“I’m really not sure, to be honest,” said Berry. “Manga in Japan is more popular than their counterpart comic books in the U.S., but both cultures have a history of associating pictures and art to help tell a written story. As Japan embraced digital technology to take it a step further, I don’t think many companies tried to do the same in the West, so perhaps it’s just a matter of being more exposed to that kind of storytelling format.”

Many developers have supplemented simple pictures with action and puzzles, which can help break up long stretches of reading — such as in Aksys Games’ popular title 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors or Capcom’s Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney series. However, it probably doesn’t help that visual novels often contain anime tropes (like the overused high school setting and blushing, androgynous characters) that can alienate many Western gamers and — in addition to the amount of reading — keep them from discovering what’s enjoyable about these titles.

Hope for the future

A little-known studio in Melbourne, Australia called Tin Man Games may have what it takes to breach the divide between reading and games.

Most recently, it released the digital “gamebook adventure” Judge Dredd: Countdown Sector 106 on Android (it hit iOS last year) and partnered with San Diego, Calif.-based Black Chicken Studios for the successful Kickstarter Holdfast. Its mobile game Trial of the Clone — by Zach Weiner, the author of the webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal — featured the voice narration of geek-culture idol Wil Wheaton (aka Wesley Crusher on Star Trek: The Next Generation). That in particular is a great example of how to popularize the genre, especially in a time when e-books are changing our expectations of how we interact with text.

Like visual novels, gamebook adventures involve much more than reading, and Tin Man’s digital versions of traditional — and entirely new — gamebooks remove much of the pen-and-paper calculations of choose-your-own-adventures, streamlining them for modern audiences.

Like visual novels, gamebook adventures involve much more than reading, and Tin Man’s digital versions of traditional — and entirely new — gamebooks remove much of the pen-and-paper calculations of choose-your-own-adventures, streamlining them for modern audiences.

Neil Rennison didn’t always think small. Before he started Tin Man Games and created its gamebook engine, he founded Fraction Studios, which has worked on hit racing franchises like Need for Speed. “I’d always had a bit of a love affair for gamebooks in the ’80s,” he told GamesBeat, explaining that he shifted focus because he needed a change. “They were the first kind of portable gaming. There were no Nintendo DSes to take on your holiday trips, so instead I took piles of these gamebooks with dice and pencils.”

Some of his favorites growing up were the Fighting Fantasy series. His first was Ian Livingstone’s Deathtrap Dungeon. “We’re actually publishing that book,” said Rennison. “We got the rights to it. So we’ll be publishing that this year, which is very odd. It’s kind of a pinch-yourself moment, really.”

Tin Man has adapted other Fighting Fantasy gamebooks like Blood of the Zombies and House of Hell — adding bookmarks, achievements, and other features. These might sound like embellishments on a tired genre, but Rennison reminds us of the impact these games — and in turn, other text adventures — have had on the medium as a whole.

“The weird thing is that when you play a modern computer game these days, it’s essentially the same decisions that you’re having to make, just not in a written form,” he said. “They’re in more of an action form, where you’ve got to [decide] which button combination you’ve got to make or which 3D room you got into next.

“The weird thing is that when you play a modern computer game these days, it’s essentially the same decisions that you’re having to make, just not in a written form,” he said. “They’re in more of an action form, where you’ve got to [decide] which button combination you’ve got to make or which 3D room you got into next.

“Even though it’s an old kind of genre, it’s still so relevant to today’s game design principles. I’d even go as far as to say they set some of the wheels in motion to modern game design.”

Now gamebooks are borrowing elements from the very games they inspired. The Kickstarter project Holdfast, which has surpassed its target funding goal of $20,000, tells a story of “dwarven vengeance.” Its system verges on more role-playing-game complexity, taking the genre in a new direction.

It’s a challenge and just one way that these games can rope in a wider audience.

Bringing the genre into a new age

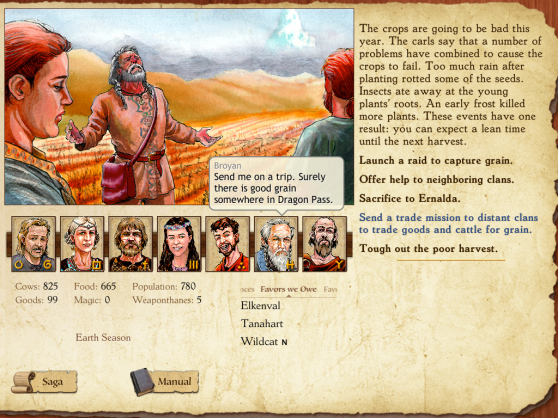

Tin Man Games isn’t the only developer leading this revolution. A Sharp, the maker of 1999 “storytelling-strategy game” King of Dragon Pass, refined the title for iOS in 2011 and has since achieved more than 30,000 downloads. It not only added new interactive scenes and Game Center achievements, for example, but also simplified gameplay and squashed bugs. The user experience is far better, from a manual that players can access anytime to “livestock” instead of sheep and pigs.

But there’s still a lot to see, just like in visual novels and gamebook adventures. “No scene will randomly repeat for at least five game years,” wrote designer David Dunham.

But there’s still a lot to see, just like in visual novels and gamebook adventures. “No scene will randomly repeat for at least five game years,” wrote designer David Dunham.

That’s a lot of text, but King of Dragon Pass is, foremost, a game. That can work in a developer’s favor.

“The fact that you’re reading is a huge challenge because obviously, that’s a barrier for a lot of people,” said Rennison. “But it also can work both ways in that because it’s a game … that can break down the reading barrier for some people.”

It’s important to put new pressures on the genre to further overcome this obstacle. “What worked quite well in paperback form in 1986 doesn’t necessarily work so well in 2013, and it’s kind of knowing what to keep in and what to take out and what to evolve or move forward,” said Rennison. “And there are various different companies that are making gamebooks as apps and games at the moment, and I think we’re all pushing in slightly different directions to try out new things and see what we can do with the genre.”

That’s perhaps easier to do with Tin Man’s games, unfortunately, than with visual novels, whose Japanese developers might not want to change their style to appeal to Western audiences.

That’s perhaps easier to do with Tin Man’s games, unfortunately, than with visual novels, whose Japanese developers might not want to change their style to appeal to Western audiences.

In an effort to reach more players, Rennison’s studio even experimented with business models by offering a science-fiction gamebook adventure with a few chapters available for free and the rest as a paid download. But that didn’t result in the traction they would have liked. “I think the problem is that we’re such a niche area that in order for freemium with in-app purchases to work, you need a large install base,” he said.

Reinventing the basics

Part of growing that base and making these games better is figuring out what people found frustrating about classic gamebooks. “Obviously, keeping record of all your stats and all your items and everything as you go about the story is quite time-consuming,” said Rennison. Tin Man’s games monitor everything for you.

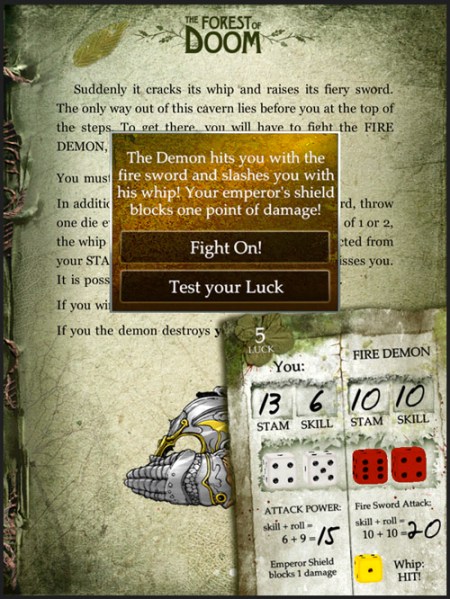

“We need to put things in there that appeal to gamers,” he said — like music and cinematic openings, which improve the presentation. “And obviously, the dice is a big issue because you roll dice in gamebooks, and we needed a way of getting around that, so we have fully 3D physics dice. You actually shake your iPad or your iPhone or your Android phone or tablet, and the dice bounce around the screen.”

He also proposed the idea of removing the dice entirely and adding in something completely different. It’s all part of trying out new mechanics and seeing what players respond to.

In Tin Man’s upcoming Forest of Doom, based on the classic Fighting Fantasy gamebook, the studio added a map that shows monsters and previously visited locations. “A lot of the time, when we were kids, we’d map it out on a piece of graph paper,” said Rennison. “But it feels like it needs the app to actually do that mapping for you.”

In Tin Man’s upcoming Forest of Doom, based on the classic Fighting Fantasy gamebook, the studio added a map that shows monsters and previously visited locations. “A lot of the time, when we were kids, we’d map it out on a piece of graph paper,” said Rennison. “But it feels like it needs the app to actually do that mapping for you.”

Artwork and voice actors can make these games stand out more, too. Bringing in Wheaton as a narrator (a “happy accident”), for example, helped raise awareness for Trial of the Clone. “Any little thing like that that you add in, in marketing terms, really can bring something alive a bit more” and increase visibility, said Rennison.

He admitted that some of Tin Man’s early gamebook adventures were too hard; introducing difficulty settings and a bookmarking system has made a difference. These features, including what’s essentially a casual reading mode, make the apps accessible to more people. In addition, achievements break up the story length and help players achieve a sense of completion by encouraging them to explore a game more thoroughly.

After all, these games are deep and replayable, a desirable feature of many console titles.

“It’s difficult to try to get that spread of variety and length but also to make that fun,” said Rennison. “People have got to be compelled to want to keep going through it.”

Finding fresh ways to redefine an experience can bring a whole new community to a genre. It could be the answer to saving this one. No one said these games had to be niche forever.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More