Seamus Blackley, the co-creator of the Xbox, passionately believes that gameplay will triumph in the game business. That is why he and his new startup are relying on a team of famous designers from Atari to make a series of games for the Apple iPhone and iPad.

Seamus Blackley, the co-creator of the Xbox, passionately believes that gameplay will triumph in the game business. That is why he and his new startup are relying on a team of famous designers from Atari to make a series of games for the Apple iPhone and iPad.

The idea that he and his partner, chief executive Van Burnham, have dreamed up is to use the creators of the best arcade experiences from the golden age of Atari in the 1970s and 1980s to create games for the “new arcade” on iOS devices.

“We are looking at the new arcade, and 99 cents on the iPhone is the new quarter,” Blackley (pictured above), president of the startup Innovative Leisure, said in an exclusive interview with VentureBeat. “People are playing on all these new devices and are finding the joy of the arcade games.”

The “Jedi Council” team includes Ed Rotberg, creator of the classic Atari game Battlezone; Owen Rubin, creator of Major Havoc and Space Duel; Rich Adam, creator of Gravitar and co-developer of Missile Command; Ed Logg, co-creator of Asteroids and Centipede; Dennis Koble, creator of Touch Me and Shooting Gallery; Tim Skelly, the only non-Atari veteran arcade game designer who worked for Cinematronics and created games such as Rip-Off; and Bruce Merrit, creator of Black Widow.

“This is the dream team from Atari,” Blackley said.

All told, there are 11 arcade game creators who are banding together at Innovative Leisure. They are joined by young interns in their 20s who will work with the veterans to help design new apps. Altogether, Innovative Leisure has 30 employees — a big team for a fledgling startup. To finance the overhead, Blackley has invested his own money and raised funds from publisher THQ. Next week in Las Vegas, at the industry’s Dice Summit, Blackley and his team members will talk about their vision for “the new arcade.”

Supercade

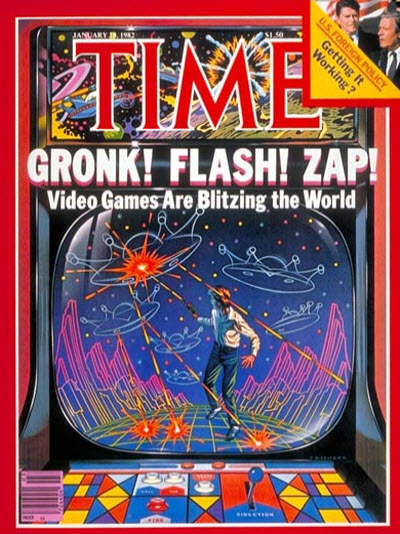

The startup has been a long time in the making. Some of the Atari veterans participated in a Time magazine cover story on video games in 1982; it was titled, “Gronk! Flash! Zap! Video games are blitzing the world.” But a couple of years after that, Atari changed ownership and the golden age of arcade games came to an end.

The startup has been a long time in the making. Some of the Atari veterans participated in a Time magazine cover story on video games in 1982; it was titled, “Gronk! Flash! Zap! Video games are blitzing the world.” But a couple of years after that, Atari changed ownership and the golden age of arcade games came to an end.

Burnham got to know many of the creators from Atari while writing her 2003 book, Supercade: A Visual History of the Videogame Age 1971-1984. She introduced them to Blackley. They realized that the small group of designers had a tight relationship, getting together on an annual basis for the Gonzo Invitational, a golf tournament for Atari alumni that began in 1998.

Blackley helped launch the Xbox in 2001 and left Microsoft in 2002. He worked at game-production startup Capital Entertainment Group before becoming an agent for game developers at Creative Artists Agency. There, he represented legendary designers such as Will Wright (The Sims) and Tim Schafer (Psychonauts), helping them get a bigger ownership stake in their companies and properties in negotiations with publishers.

Meanwhile, Burnham and Blackley began building their own arcade in a Los Angeles warehouse. Dubbed “Supercade,” it has tons of old machines that Blackley repaired and refurbished himself. It is a vast place with row upon row of machines with flashing lights and ringing bells. Walking down the aisles is a trip down memory lane: Every person who visits Supercade becomes a kid again as they find an arcade machine from their childhood days.

He and Burnham curated and hunted down machines that would best illustrate a history of gameplay. And when Blackley left CAA last summer after eight years, Supercade figured big in his plans for his next gig.

“We had that big collection of games, and we love the history of game design,” Blackley said. “I’m lucky because I love games and following that love has always done me well. Once we figured out the iPhone is the new arcade, that games from the old days fit this new audience and their on-the-go lifestyle, we knew what to do. There is already a group of people who know how to operate and innovate in this space. They had the longest string of hit games in history. And they wanted to get back together again.”

Getting the band back together

The idea, Burnham said, was to “get the band back together.” Many of these veterans went on to careers at Apple and other places outside of gaming, and most of them thought the arcade days were over. But they all considered their time at Atari to be the most rewarding in their careers and are reunited thanks to Blackley’s vision.

The idea, Burnham said, was to “get the band back together.” Many of these veterans went on to careers at Apple and other places outside of gaming, and most of them thought the arcade days were over. But they all considered their time at Atari to be the most rewarding in their careers and are reunited thanks to Blackley’s vision.

“I’m here because of Seamus,” said Rotberg (pictured right), who works remotely from Grass Valley and is excited to be working on games again. Like the other veterans, Rotberg is paired with an intern and are working on a new title together.

“These kids are thrilled to learn how to make games with the inventors of gameplay,” Blackley said.

The team came up with 30 game ideas and whittled them down to 10. They pitched them to THQ, which said that it wanted all of them. So far, seven of those titles are in the works. Most of them are already in prototype form.

“It’s been very easy to support Seamus and his team on Innovative Leisure because they are all super-smart dudes who care about games,” said Lenny Brown, vice president of creative and business development at THQ.

Blackley said that the creators of coin-operated games know how to do things like grab the attention of the gamer in the first few seconds and make him feel like he’s accomplished something in three or four minutes of play.

Coin-op games had to stand out in an arcade and generate money for weeks in order to be profitable, so the process of making them and refining them was very rigorous. And while the iPhone has far more computing power than the old machines did, it is constrained in terms of memory and processing resources compared to modern consoles. So designers have to know how to efficiently use the device’s resources.

While many other big companies have been accused of copying or making derivative titles, Blackley believes strongly in making original games.

“We are carrying on where Atari left off, focusing on innovation in gameplay,” Blackley said.

“We are carrying on where Atari left off, focusing on innovation in gameplay,” Blackley said.

Blackley said the team can work together in the arcade warehouse and be inspired by the different games that are there. He says it is important that the group works in a collaborative way. They are divided into different projects, but, as at Atari, they are free to help — and offer criticism — on other projects.

“They have worked together before, and they have a development rapport that is magical,” Blackley said.

THQ has first right of refusal on the games, in exchange for financing. That’s a little risky, since THQ is on shaky financial ground. But Blackley said his team is low overhead, and it is a more efficient use of THQ’s money. And if THQ chooses not to publish a game, Innovative Leisure is free to take the games somewhere else. Indeed, companies like Atari itself might want to tap its former designers to make modern versions of its old games.

But Blackley says the focus will be on original games. He is knee-deep in the creative process. As a former game developer (and theoretical physicist) who created physics-based games such as Trespasser, Blackley likes to get technical. He feels at home writing code and talking about it with his team members.

“We have to create a quality experience, hone it, and tweak the crap out of it so that you get the same level of gameplay that people demanded in the arcade era,” Blackley said. “It’s scary as shit if you don’t understand gameplay.”

Blackley said his team of veterans had license in the old days to do “crazy stuff,” using a rapport to riff on each other and craft wonderfully creative games where you could shoot worms or missiles and play with roller-skating bears.

Making modern games

The process of making games today is far different from what it was a few decades ago. Owen Rubin (pictured right) said that when he joined Atari in 1976 as one of the first programmers, he had to work with teletypes, oscilloscopes, and circuit boards to “program” his arcade machine.

The process of making games today is far different from what it was a few decades ago. Owen Rubin (pictured right) said that when he joined Atari in 1976 as one of the first programmers, he had to work with teletypes, oscilloscopes, and circuit boards to “program” his arcade machine.

“I did everything by hand,” Rubin said. “To make sound of a splat, I had to record the sound as I dropped wet towels into a shower. We were making it up as we went.”

Rubin learned what he had to and soon was creating one game after another, including Space Duel and Major Havoc. He left in 1984 and went to work at Apple and a variety of other companies. All the while, he stayed in touch with his Atari friends. When Blackley approached him, Rubin jumped at the chance to “reinvent games.”

Rotberg worked at Atari’s coin-op division from 1979 to 1981, and then he came back for a second stint from 1986 to 1991. He made everything from a baseball game to Battlezone, which used cool 3D vector graphics and turned into a runaway hit. He went on to work at Apple, 3DO, Sente, and Silicon Entertainment. He moved to Grass Valley, Calif. and then started consulting on entertainment projects.

“Games are in my blood,” said Rotberg, who serves as Innovative Leisure’s chief technology officer. “What’s interesting to me now is that the smaller-scale games work for mobile devices. This isn’t something that takes hundreds of people and tens of millions of dollars. Instead, it is remarkably similar to what we did in an earlier age.”

“We have tried to recreate the environment at Atari, where we would wander into each other’s labs and share invaluable input,” Rotberg said. “That’s what we do now, and I have to say I learn from the interns. But we saw an instance where an intern’s code failed. None of us older guys would have made that mistake because we can think about it at the machine level. It’s a crap shoot. But Seamus has put together what was the single most talented group of people that I have had the fortune to work with. I am having a blast for the first time in a long time.”

Original is best

Rich Adam (pictured right), feels the same way. He started at Atari to work on pinball machines. By the time he left in 1983, he had worked on Missile Command with Dave Theurer and did the design for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. He went on to work at Bally Sente, Electronic Arts (where he created the first PGA Tour golf games), Interactive Network, and Silicon Entertainment, then he went on to become a consultant.

Rich Adam (pictured right), feels the same way. He started at Atari to work on pinball machines. By the time he left in 1983, he had worked on Missile Command with Dave Theurer and did the design for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. He went on to work at Bally Sente, Electronic Arts (where he created the first PGA Tour golf games), Interactive Network, and Silicon Entertainment, then he went on to become a consultant.

“It is funny how the market has come all the way around to return to the arcade experience,” Adam said. “People are playing in a more casual manner again.”

Adam also cherished the collaborative environment at Atari. When he heard what Blackley had in mind, he thought it was a great idea to bring back “the best engineering group I ever worked with.”

“It was hard to get your shit done because others came in,” he said. “But they would come in and give counsel. We had this downtime as we waited to get our code back. So we would graze the labs and see what others were doing.”

Today, making games is different. “In the old days, it was assembly code,” Adam said. “Today, you have tools that can get your concepts into playable fashion much more quickly. But we still have one thing in common. We are in the novelty business, where it has to be original. It is hard to be novel now. The Zyngas of the world want to throw out something quickly or copy it. We’ll take our time and work longer to do it right.”

Blackley says the games will start coming out this summer on the iPhone and iPad. The company will market them and rely on help from THQ to get the word out, but the expectation is they will take off because they have “awesome gameplay.”

“They’re all playable and awesome,” he said. “More ideas are coming up from the old guys and the new guys. We want to have a string of really innovative games.”

[Photos: courtesy of AIAS/game designers]