The first Silent Hill movie amazed and impressed in 2006. Amid an ongoing stream of offensively bad Hollywood and German adaptations, Silent Hill was one the few elite video game films that didn’t outright suck. In fact, it was pretty damn good, and certainly better than any actual Silent Hill game released since Silent Hill 3 in 2003. I think the part where most people realize whether they’re a fan or not is when Pyramid Head rips the skin off a woman and throws it at two of the main characters.

However, the original came from the dark mind of Roger Avary, Quentin Tarantino’s lesser known scriptwriting co-op buddy on Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. Avary was not involved in the recently released sequel, Silent Hill: Revelations 3D. Stepping in as both writer and director is Michael J. Basset, who previously worked on … nothing anyone’s ever heard of.

Silent Hill: Revelations 3D was met with universal critical disdain, earning a 15 out of 100 on Metacritic. Slant Magazine’s Calum Marsh said the film “fundamentally misunderstands the appeal [of] its source material.” GamesBeat questioned writer/director Bassett on staying true to the source material, delivering the scares, and UFOs.

GamesBeat: In the first Silent Hill movie, I remember that pretty much every character was female. The studio even had them go back and add Kim Coates, I believe, as the detective. And Sean Bean had his role extended, just so it wasn’t an all-girl cast. Did that impact the second film at all?

Michael J. Bassett: No. … It’s an interesting question. I had heard that Christophe [Gans] had wanted to make an all-female movie, right? He was really serious about that. Obviously, it didn’t quite turn out that way. That was a product of his sensibility. Me, I don’t really think along those lines. I want to populate the world of this movie in a more balanced way, without any kind of agenda one way or the other.

Obviously, making a sequel to the first one and knowing that the central character is going to be this young girl, Sharon Da Silva, from the movie, or Cheryl if you play the game. … She grows up and becomes Heather Mason. Game three is Heather’s story, and that’s how it worked out. Her relationship with her father is the central plank of the game and of my movie. The first movie was the story of a mother looking for her daughter. This movie is the daughter looking for her father.

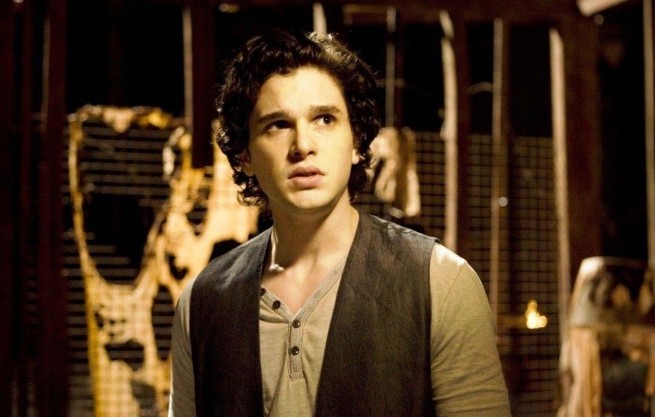

Even Kit Harington was … for me, it was lucky that he walked into the audition then, because I’d never get him now. He’s Jon Snow on A Game of Thrones. But at the time, that hadn’t been broadcast. All I knew is that I had a very talented young actor in front of me, and I wanted to work with him.

But no, that agenda, one way or the other, was never part of my thinking.

GamesBeat: Video game movies in Hollywood have done pretty poorly, commercially and critically. Did you struggle with that, or with anything because of that, while pitching Silent Hill, getting budgeting, and so on?

Bassett: The first thing is that this is not a Hollywood movie. This is a movie made by a European production team. The producer is French, and I’m English. There was almost no American involvement whatsoever. It’s been distributed in the U.S. by American distributors, but that’s it. The notion that it’s a Hollywood movie is monumentally incorrect. And that’s good for me. I’m a European filmmaker. I’ve never made a movie in Hollywood yet.

Not that I wouldn’t — I love Hollywood movies. But the great thing about working with Samuel Hadida, who is the producer on this picture. … I had worked with him before on a movie I made called Solomon Kane. We’d got on really well and had a great time. When he wanted to make a sequel, we talked about it. I said, “I’m a fan of the games. I love Silent Hill.” So the problem, I think, with game adaptations is that they are considered to be a very poor creative choice. But for me, that’s crazy, because some of the most creative things happening in the entertainment industry right now are coming from games. The way stories are being told, the visuals that are being deployed, the technology that’s being used. … Games are cutting-edge all the way for that. I’m a gamer of very long standing, so I have no prejudice about it either way. The difficulty is that when you’re writing a game adaptation, what you have to bear in mind is that you’re making a movie. You’re not doing a game. Movie writing and game writing are very different. What you do with characters, the mythology and the resonance of the stories — they’re all different. If you know that and you come at it in a way that’s respectful of the game world. …

I love Silent Hill, and I want to make something that’s completely true to the Silent Hill universe, but the story is an adaptation. It has to be turned into something that works as a movie narrative, not as a game narrative. There’s no branching. There are no choices. This is the story of this girl doing this thing. I want you to sit down and enjoy the entertainment I’m giving you. The participation is on a psychological level rather than a physical, interactive level.

GamesBeat: You were talking about keeping true to the games. One of the more contentious points with fans over the video game history has been the nurses — their official name escapes me at the moment — and Pyramid Head. They both first appeared in the second game. …

Bassett: In Silent Hill 2, yeah.

GamesBeat: The argument is that they were a manifestation of the main characters’s guilt and fears, the confusion surrounding. …

Bassett: … About his wife, yeah. I know where you’re going with that question. [Laughs] The thing about the monsters in Silent Hill is that they’re supposed to represent the psychology of the principle character. The notion is that what you give Silent Hill, you get back from Silent Hill.

Or that’s certainly how I read it. Now, we were talking about how there’s no agenda. … But in a way, there was. In the first movie, Christophe had used Pyramid Head. They called it “Red Pyramid” or something, but he’s Pyramid Head. The design of the head was slightly different in the movie for practical reasons. The nurses appear as well. So I couldn’t unpick them. They existed in the world. It turns out that Pyramid Head was an iconic creature, and the nurses were really enjoyed by the audience. So we wanted to use them. What we had to do to make it seem rational to me was understand the psychology of why — certainly with Pyramid Head — why he would be in Heather’s journey. Because he shouldn’t exist now. He was in the first movie. He is generated by the central character in game number two. For Heather, why is he there, and what does he represent?

Now, to me, this is obviously something where everyone can interpret it and people can disagree with me, but my rationale was this: He’s the executioner — or a manifestation of the executioner — from when Silent Hill was a pioneer town and a prison colony, and these things happened back in the day. He’s the corruption of that spirit, if you like. He is part of the masculine presence within Heather’s world. She’s looking for her father. Pyramid is a masculine presence. I wanted that to be reflected by another monster we create, who is a very feminine monster. So I wanted this kind of antagonism between masculinity and femininity to be there.

When you see the movie. … I can’t explain it without giving away key plot points, but Pyramid Head is not what you think he is. His purpose is not as clear-cut as “He’s a baddie who goes around ripping off people’s flesh and chopping them up.” He means something more to her. I hope that, though it’s not the pure essence of game number two, there is an argument for him to be there. If he exists already, he’s there, but now I’m using him for a particular purpose.

GamesBeat: When making a film like this, especially one that’s going to be in 3D, how do you go about setting the atmosphere? In the game, you have that constant fear of “Am I gonna die? Am I gonna get a game over?” Because it’s interactive, it’s easier to immerse the player and get the fear going. How did you specifically go about trying to replicate that level immersion and the fear that fans are used to?

Bassett: Well, you have to remember that movies existed long before games ever existed, and they managed to create fear in the audience without that notion of interactivity. The only game that’s ever really, truly frightened me … well, Silent Hill did. It creeped me out. It frightened me. But the notion of dying — there’s never any problem with dying. You respawn somewhere else, and you play the level again. But I remember playing the first Aliens vs. Predator game. You probably don’t remember that one. You might be too young. [Editor’s note: My first console was the Atari 2600! –Sebastian] The one done by Rebellion in the U.K. That scared the shit out of me! Partly because there was no respawning. You had to play the whole damn level again. Suddenly, there was a value attached to dying: “Do not die; otherwise, you’ve gotta go back to the beginning.” There were loads of complaints about it. But the truth of the matter is, it suddenly had a value. You don’t want to die. You have to play the game in a way that you can’t do all these fast autosaves. “I’m gonna autosave before I open the door. Oh, I got killed by a monster. OK, back to the outside of the door again.” Which, to a certain extent, is my way of playing a game. Having that removed from me made it a very different gaming experience.

I’ve completely digressed, but that’s what I meant by saying that a game can frighten you,because you’re invested. In a movie, you’re only frightened if you’re invested in the characters. The technique you use, hopefully, is to get an actress — or an actor, but in my case an actress — to give a performance that you are sympathetic to, that you are engaged by. You understand her journey, and you want her to go on that journey but also not go on that journey because it’ll be a horrible frightening experience for her. Only then are you engaged, and only then can you be truly frightened.

You sort of know that the central character’s not going to die halfway through the movie. Nobody’s ever done that, really, apart from Janet Lee in Psycho, which was a genius thing from Alfred Hitchcock. The technique is to engage the audience with a character. And then, of course, the joy of Silent Hill — the game that you’re adapting — is that it presents you with this fantastic catalog of environments and techniques and designs to try and scare the audience. We’re going into corrupt asylums and hospitals and things like that. These are places that are familiar to the audience on one level, and then when you start corrupting them and changing them, they’re the most frightening versions. It’s rusty and grim, and you have these faceless nurses wielding surgical blades. You have one character that’s tied to a gurney, and the nurses are about to eviscerate him. That’s a nightmare that everybody has experienced in a hospital. Same as when you’re in school. High school is an inherently frightening, twisted place for some people because you have no choice but to go there. You take the familiar and make it a little bit twisted. That makes it more frightening.

GamesBeat: One of the staples of the Silent Hill games are the secret alternate endings.

Bassett: Ah, yes, the UFO endings.

GamesBeat: Right. The UFO ending, the dog ending. … I was wondering if that was something you had considered or were doing for maybe the home video release?

Bassett: We absolutely considered it. The difficulty is, doing that stuff costs money. At the end of the day, I figured it was better to spend the money on the screen for the main movie. We’ve certainly talked about doing something on the DVD release — a little treat for the fans. It would be lovely to do it. It would be funny and, I think, well received. But sadly, there’s nothing built into the theatrical version. Stay tuned for the DVD release. You never know what you’re going to get.