Click here for all of GamesBeat’s coverage of the 2015 DICE Summit.

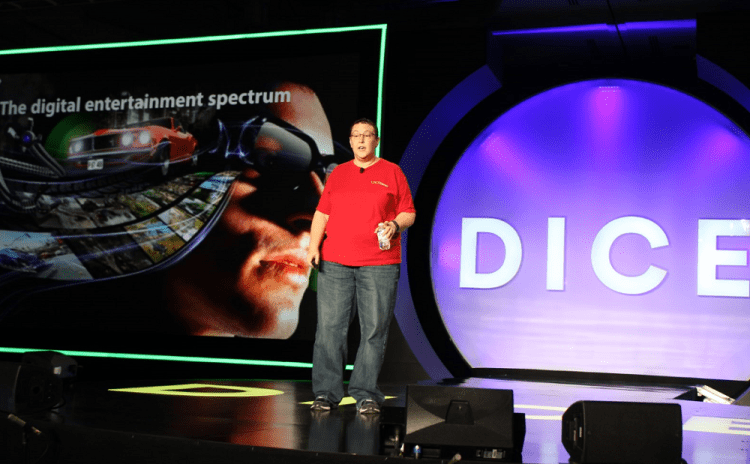

LAS VEGAS — Tracy Fullerton believes that games are poised at a critical moment of definition and change. Speaking at the 2015 DICE Summit today, the director at USC Games (the University of Southern California’s game-design program) says that several “bosses” stand in the way of reaching what she calls an “Age of Play.”

Fullerton predicts that we will see a time where the game industry will become so broad that it becomes a part of the larger entertainment spectrum, bringing about an age where the concept of “nongamers” will disappear. She sees a future where public social systems will turn to game designers for leadership, or where game makers will run community campaigns. What she calls “new superheroes of game design” would bring subjects like health care or city planning to games, helping society deal with our greater challenges.

Education has just started to experiment with games as an learning tool. While she admits that it may be far out, Fullerton sees a future where teaching and game design are a combined discipline, where designers would be teachers, and teachers would be designers. She feels that we could see a day where instructors without game design experience would be under-qualified for the classroom.

This culture would help cultivate future creators that would use games to help society address all of our issues, from health to civic engagement. City planning, fine arts, social work, and architecture could all benefit from games. But this can’t happen as long as we’re only training game designers for the entertainment industry, she stresses.

“A certain level of literacy in design may be critically important to the world’s citizens,” Fullerton says, addressing an audience of designers. “You are all wizards. How would you use your talents?”

Boss: a limited view

Fullerton says that the industry is stuck in viewing games as only entertainment, and implores game makers to imagine the bigger possibilities. She says that this limited view is a wall that stands in the industry’s way, and that’s mostly because most aren’t trying to do anything differently.

Boss: Community

“If we want everyone to play, everyone needs to be able to make,” says Fullerton.

While she says that the industry is making progress, we still have a long way to go before the culture of development is open to all.

“It isn’t like you can just run an ad and expect that women and minorities will apply,” she says. “How many people do you know will respond to such a half-hearted invitation? We’ve really got to mean it.”

Fullerton believes that people of all kinds would make games if they knew they could. She says that it’s time to inspire different segments of society to imagine themselves as game developers.

Boss: Identity

The game industry is in a position where it has to defend itself from the audience it created, says Fullerton. She feels that gaming is the only industry that has focused on one segment so much that it cultivated its sense of entitlement. Now it’s a threat to the industry’s identity, she says.

Fullerton remembers a time where games were for families, girls, women, and men.

“We need to take back that sense of play for everyone.”

Ambassadors of change

Fullerton calls the next 10 years the most important that the game industry has ever faced. She says that it’s in danger of not reaching its potential, and that we could miss out on a bigger industry than we have ever imagined, saying that it “glitters with opportunity.” But it has to happen through wider culture, she notes.

Fullerton challenges all game makers to maximize their efforts towards helping games reach this goal.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More