… movie director and Monty Python alum Terry Gilliam (12 Monkeys, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas)

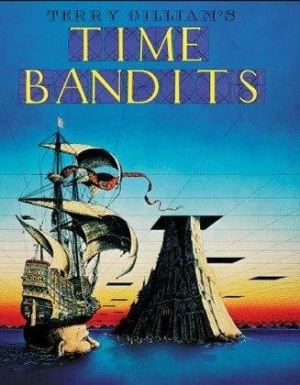

Moore: Terry Gilliam is probably my favorite director of all time. And why? Because when I was a kid, I watched a movie called Time Bandits, which is about a boy who’s sucked through a wormhole by seven dwarves who are basically the creators of the universe. God told them how to make it, and they’ve stolen God’s map of the universe, which is a time map. They run away to go and steal treasure throughout time. The boy has to go on this journey with them.

Moore: Terry Gilliam is probably my favorite director of all time. And why? Because when I was a kid, I watched a movie called Time Bandits, which is about a boy who’s sucked through a wormhole by seven dwarves who are basically the creators of the universe. God told them how to make it, and they’ve stolen God’s map of the universe, which is a time map. They run away to go and steal treasure throughout time. The boy has to go on this journey with them.

Gilliam had decided that he just wanted to make a movie where he could set it anywhere he wanted. They end up going to see Napoleon and going all the way back to fight the Minotaur and jumping through time in all these great settings. He has this way of writing stuff that’s so imaginative.

Then, when we transferred that voice to Puppeteer, we said, “We don’t want to have just one setting to set this in. We want to take them on a journey.” As we say, it’s so these people don’t get bored playing my game. I don’t want to get bored playing a game. We take them to these amazing destinations all the time that change on you. You think you’re where you are, and then suddenly, because it’s a moving theater, all the set changes come in, and you’re somewhere else. Then, as soon as you think, “OK, I’ve got that,” it changes on you again. You’re always progressing, always moving. We’re taking you on this fantastical journey.

I started off in games as a pixel artist, making animated sprites. Way, way back, we’re talking here. Then we started on the technological curve for the PlayStation. Now we’re at PlayStation 3 — and even PlayStation 4 — and we’re seeing some of that uncanny valley type of stuff. When I finished my last PlayStation game [Siren: Blood Curse for PS3 -ed], it was like, “Right. No more. No more eye-reflection shaders and all that stuff. I want to move away from realism and concentrate on the creative side.” If I want to have a 200-foot-tall wooden tiger who’s kind of sarcastic and snobby, then I will, and we do because I can. I’m not stuck in that realistic world anymore. I’m stuck in this incredible fantastical world.

I think that’s something I learned exactly off what Terry Gilliam was trying to do.

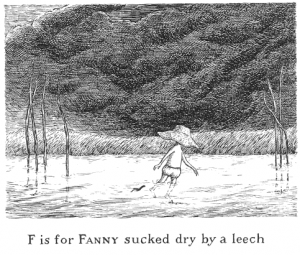

… children’s author Edward Gorey (The Gashlycrumb Tinies)

Moore: I love Edward Gorey. He does a lot of picture books. They’re all very, very dark. They’re like the A to Z of children’s names and how they die in bizarre situations. Look him up. They’re great reads. They really are great.

Moore: I love Edward Gorey. He does a lot of picture books. They’re all very, very dark. They’re like the A to Z of children’s names and how they die in bizarre situations. Look him up. They’re great reads. They really are great.

My son was born in Japan, so he’s fluent in Japanese rather than English, but I was reading this thing to him. He was giggling and laughing. It pointed out to me that children are much darker than we think they are. They don’t care. They don’t find it scary. We think it’s bad for them, or it’s scary to them, but actually, they like that kind of dark side of things. They think it’s funny, almost.

A lot of those influences went into Puppeteer — that way that we could have this dark fairy tale with this boy stolen away from Earth and shoved into a wooden puppet. His head’s pulled off and eaten, and then he’s thrown away to go and work as kitchen staff. He finds he has this magical power where he can put things on his head and use them as heads and then use those heads in the world to change things. Then he’s convinced by this psychotic, bizarre witch that’s somehow working as the cook in the kitchen to go and steal the tyrant king’s pair of magical scissors.

My son played it, and he said, “This is great! I’m really into this!” And so we wrote it so it didn’t talk down to kids. It was more aimed at the adults with the humor that kids would like here. I’ve met a lot of adults who have the mental age of kids, so I think we’re generally in the right ballpark [laughs].

… cartoon Roobarb & Custard

Moore: There was an animation that was all done with felt-tip pens called Roobarb and Custard. [It showed a] very bizarre, off-the-wall relationship between this stupid dog and this evil cat that’s just trying to hurt the dog all the time. It’s just laughing at his stupid antics all the time. That was influential. All those very English things, actually.

Moore: There was an animation that was all done with felt-tip pens called Roobarb and Custard. [It showed a] very bizarre, off-the-wall relationship between this stupid dog and this evil cat that’s just trying to hurt the dog all the time. It’s just laughing at his stupid antics all the time. That was influential. All those very English things, actually.

There are a lot of [relationships] in Puppeteer — I wouldn’t call it bullying per se, but it’s kind of, “Hold on, what about me?” Especially the relationship between the narrator and the leading lady. They’re at each other’s throats all the time. It’s interesting to watch. Plus, when you play two-player, you can either help somebody out or you can actually get in the way. It’s up to you.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More