Sony and Microsoft have made their opening moves in the next-generation video game console war. Their next big revelations will come at the E3 game trade show, and this starts with their press conferences on June 10. The age of digital game consoles has arrived, but I’m still worried that the console makers are caught in binary thinking.

In the days before the original Xbox, back in 1999, Microsoft’s knee-jerk reaction to Sony’s threat was defensive. It wanted to stop Sony’s PlayStation 2 from taking over the living room. That’s why it started on the Xbox, and then the company expanded its thinking from there. Both companies came to see their game consoles as Trojan horses, items people purchased for gaming purposes and eventually used for controlling all entertainment. Microsoft and Sony both have credibility as leaders in games, and their eyes are still on a much larger prize of being the hub for movies, music, TV, communication, and everything else.

In the days before the original Xbox, back in 1999, Microsoft’s knee-jerk reaction to Sony’s threat was defensive. It wanted to stop Sony’s PlayStation 2 from taking over the living room. That’s why it started on the Xbox, and then the company expanded its thinking from there. Both companies came to see their game consoles as Trojan horses, items people purchased for gaming purposes and eventually used for controlling all entertainment. Microsoft and Sony both have credibility as leaders in games, and their eyes are still on a much larger prize of being the hub for movies, music, TV, communication, and everything else.

But gaming was the linchpin. If they failed with that, nothing else mattered.

That’s still the case today. Some described Sony’s press event in February as rambling and Microsoft’s Xbox One announcement as a disaster. But they’re wrong. They’re simply incomplete events, by necessity. More information — some of it which they’re keeping secret for now — will trickle out over time. By the time of the launches in the fall, potential customers are going to know what they need in order to decide whether to invest in one game console or another. Sony showed off games. It needs to show more broad entertainment and services. Microsoft showed off entertainment and services. It needs to show more games.

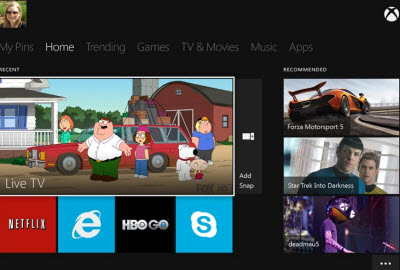

But both of them need to show that they understand the rights of consumers in a world where walled gardens are full of holes. The difficulty for these companies is that the world has moved on from completely binary thinking. Gamers watch movies. People play games on more than one device. When you acknowledge that we live in a multitasking world with multiple platforms, and when you design your experience taking that into account, then you can win big. This is the way to grab all of the marbles: being transparent, being more open than you should be, and embracing community.

“I really don’t see this as a binary answer,” said Chris Petrovic, the former head of GameStop Digital Ventures, when asked who would win. “Each of these platforms can and will capture a meaningful share of consumers’ share of time and wallet. There seems to be general consensus in the games industry that it will continue to follow the ebbs and flows of its media brethren — movies, TV, etc. — in that the incumbent platforms will still provide the richest, most immersive premium experiences for the enthusiast while the newer platforms will appeal to the masses because they win on price and convenience.”

You can bet that they’ve got the bases covered on the either or questions. Microsoft said it would launch 15 internally produced games in the first year after launch. It also said it would spend more than $1 billion developing games in this generation. Sony can expand its PlayStation Network and tap into its entertainment properties so they work on PS4. Their approaches to their initial revelations so far reflect some choices. Microsoft chose to focus on non-gamers. Sony chose to focus on the hardcore.

The trick is to pay attention to both sides of the binary choices and give people more than just the basics. You don’t want to be perceived as failing to “get it.” And you have to act like you’re responding to and fostering a community.

The trick is to pay attention to both sides of the binary choices and give people more than just the basics. You don’t want to be perceived as failing to “get it.” And you have to act like you’re responding to and fostering a community.

With every console announcement, fans look for what they want. They want to make this product their own. If what they want isn’t in the console, they complain. With Microsoft, fans didn’t see enough games. With Sony, it was the opposite. They saw lots of games. But fans also complained about how Sony’s event dragged on. They complained about how Sony didn’t even show its box. In both cases, the companies defended themselves by saying they wanted to hold something back and save it for E3.

In the absence of a ton of games to show (OK, they did show EA Sports, Forza, Call of Duty: Ghosts, and a new one called Quantum Break [below]), Microsoft talked about technology like cloud processing, more accurate Kinect, and the instantaneous switching made possible by having three operating systems. Those could turn out to be big advantages. Sony mostly ignored such technical talk, saving it for the geeks who cared about it but leaving some questions hanging in the open. Sony did point out its advantage of having more processing power fully dedicated to running games (Microsoft has to divert precious silicon to handle Kinect’s constant processing requirements). That is how these machines are basically different.

In both cases, nobody answered all of the questions that gamers had. The fair criticism is that they should have had more solid answers on the consumer rights issues that people care more about these days: backward compatibility, used games, and always-online play. All of these relate to whether a consumer has gotten a fair shake, can preserve their investment, and can choose how much they want to be engaged with one product in a sea of other products that they use. By moving to crack down in some way on used games, the companies are taking back something that they once gave as a right to consumers under “fair use” agreements. They should have seen the concern coming from their fans (based on the fan reaction to Electronic Arts’ always-on debacle with SimCity) and headed it off as much as possible. Microsoft and Sony say they have policies in place that will fully describe what they intend to do. That’s not completely reassuring to consumers.

The problem is that, as with the actual launch date and the pricing, is that a competitor would love to know how its rival will deal with these consumer rights issues and act on it. Policies are the easiest thing in the world to change or copy. Software is next. And hardware is the hardest. But in a digital world where anything is possible, these problems have to be viewed in a different light. With backward compatibility, putting in the hardware to make an old game work on a new system is very expensive. It means, at the very least, you would have to put an IBM chip in a box that now has an AMD chip. On top of that, gamers care about backward compatibility in the beginning of a new console generation, but they rarely play old games on new systems.

The problem is that, as with the actual launch date and the pricing, is that a competitor would love to know how its rival will deal with these consumer rights issues and act on it. Policies are the easiest thing in the world to change or copy. Software is next. And hardware is the hardest. But in a digital world where anything is possible, these problems have to be viewed in a different light. With backward compatibility, putting in the hardware to make an old game work on a new system is very expensive. It means, at the very least, you would have to put an IBM chip in a box that now has an AMD chip. On top of that, gamers care about backward compatibility in the beginning of a new console generation, but they rarely play old games on new systems.

But the digital realm is where this gets interesting. With cloud streaming technology, it’s technologically feasible to host a game in a data center and let someone play it with any web-connected hardware. If they wanted to, Microsoft and Sony could put digital versions of their old games up into the cloud and make them accessible for consumers. But then we get to the real issue here: a scarcity of engineering talent. The time and resources it takes to do this right could be better spent making a new game system and its live services better.

Those are logical explanations for ditching backward compatibility. A similar case could be made for requiring an always-on connection and for curbing used game resales. But these problems expose a lack of trust. Consumers don’t like walled gardens anymore, and they mistrust anyone who has one. Sony and Microsoft have to regain their trust by showing off outstanding games that will make them drool. And they should also unveil something in the digital realm that truly sets these consoles apart from the last generation.

These machines have gone digital. They’re web-connected. Microsoft will have 300,000 servers available to provide services to them. We want to be so impressed with what those services and digital games can do that we’ll forget about those rights issues and gladly fork over our money. In fact, I hope that we exit this PlayStation 4/Xbox One generation thinking that digital gaming — always-connected and easily accessible — is better than traditional disk-based gaming.

In this column, I’m guilty of my own binary thinking. At E3, we’ll also hear from Nintendo. Maybe it would be cool if a console maker convinced Nintendo to give up hardware and make its software available on a rival platform, as an exclusive king maker.

And beyond E3, gamers will be listening to what Apple has to say about gaming at its own Worldwide Developer Conference. They’ll also be figuring out what happens with Android solutions such as Ouya. Gaming experiences are going to be everywhere. The more we focus on just one thing, the more we’ll be surprised by another. I’m not sure what to call it. But whatever the opposite of binary thinking is, do that. That’s my advice for Sony and Microsoft.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More