I’ve traveled the world to see the gaming industry, going to faraway places like Helsinki, Finland; London; Marseille and Angouleme, France; Amsterdam; and Shanghai. And in those places, I’ve seen thriving game companies aided by the strong hands of incubators and government support. Now it’s time to take these lessons from abroad and apply them at home. By comparison, the U.S. has a laissez-faire approach that I believe will come back to haunt it.

It’s time for the U.S. industry to do more to support its game startups, or the U.S. will fall behind. I think that the U.S. government and corporate giants like Intel, which recently pledged to invest $300 million in making the tech and gaming industries more diverse, should start nonprofit incubators to help game startups get off the ground. They should also do this for tech companies in general, but let’s focus on gaming. Mobile games have become a $30 billion business worldwide, larger than the console software industry, according to market researcher Newzoo. Mobile is the fastest growing part of gaming.

And the U.S. is already behind. Only 9 of the top 20 grossing games on the App Store were made in the U.S. We’re not in a crisis of having a shrinking game business, a bad job environment, or weakening overall ecosystem yet. But we shouldn’t wait until that day comes. With mobile gaming, the world is truly “flat,” where anybody, anywhere, can make a hit game. (That’s a reference to Thomas Friedman’s bestselling book, “The World is Flat,” which chronicled how the Internet and technology are pushing globalization forward.

Borders have melted with the arrival of app stores that allow indie developers to reach the entire globe and a billion people with their games, said Ilkka Paananen, chief executive of Supercell in Helsinki, in a presentation to journalists in November.

“All that matters now is the quality of the game and its innovation,” he said. “All of a sudden, companies could access a billion consumers from a very distant location, like Helsinki.

Helsinki is doing it right. But I don’t see the U.S. doing what is necessary to help game companies. I’m not the only one who’s feeling eager to boost the fortunes of game entrepreneurs in the U.S. Sana Choudary, chief executive of San Francisco’s YetiZen, a game startup accelerator, told me that she would welcome more government and corporate support of game startups. It’s not enough for some states to offer tax breaks, which are really targeted at attracting bigger companies and stealing jobs from other regions. She said that the government can step in and take a lot of the riskiest investments in the tiniest startups.

“I agree completely,” said Tim Sweeney, chief executive of Epic Games, the North Carolina company that set up its own $5 million fund for developers this week. “These projects are driven by talent, genius, and ability of individual developers. But there’s a point where you have to buy some stuff. You have to spend money to make it. The return on investment can be huge. At every stage of growth, the investment you make is doing a lot of good.”

Sweeney built his first game in 1991 after earning money mowing lawns for two summers. Today, it takes more people and money to make games, even among the indies who are creating mobile games. The government, or a big company like Intel, could create nonprofit incubators that foster the tiniest game studios. Those incubators could take people with ideas for games and train them to be real business people who create jobs and pay a large amount of taxes back into the system over time.

The tiny country of Finland, with 5 million people, is making us all look bad by comparison. It has hit the jackpot with government funding for startups, and the result is games like Angry Birds and Clash of Clans, which are known the world over. The Finnish government’s investment arm, Tekes, puts more than $150 million directly into startups each year. Supercell, the maker of mobile games like Hay Day and Clash of Clans, received more than $450,000 in loans from the Finnish government. If it had failed, it wouldn’t have had to pay that money back. Supercell hit a home run with all three of its games (Boom Beach included), and it generated more than $300 million in taxes for Finland.

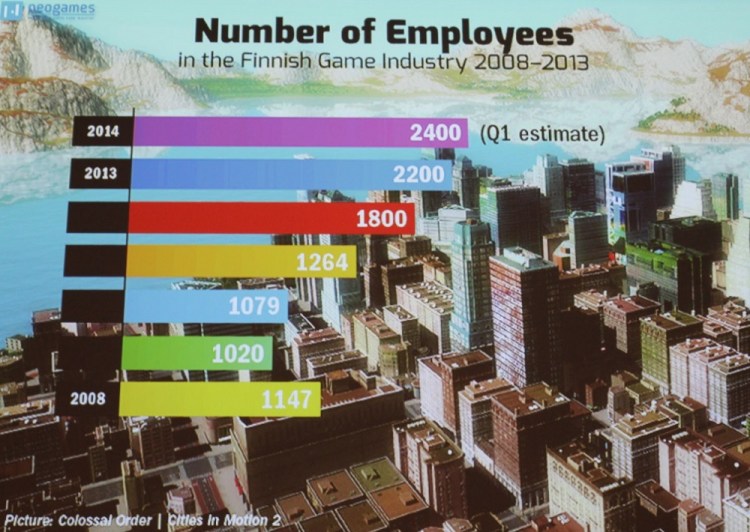

Supercell hasn’t reported its 2014 revenues yet, but I would bet that it made more revenue in mobile games than any U.S. mobile game company. It has no more than 150 people, but you can play its flagship game in more than 150 countries, said Koopee Hiltunen, director at Finland’s NeoGames nonprofit group. Finland has 17 schools that offer different levels of game education in Finland, and college-level education is offered for free to all Finnish citizens.

Finland has fundamentally changed the mindset of young people. Rather than work for big companies like Nokia, they now want to work for startups, said Artturi Tarjanne, a founder of venture capital fund Nexit Ventures. And the VCs in Finland are happy because they can move to later stage investments and put money into startups that have already had funding and worked out a lot of their early-stage challenges.

Any country can jumpstart a mobile game business. Finland’s game industry generated $1 billion in revenues in 2013, according to NeoGames. That’s up from just $45 million a decade ago. It had the patience and foresight to invest early. Other countries have taken notice. Lithuania, the United Kingdom, France, Sweden, Canada, Singapore, India, the Netherlands, Estonia, Germany, Thailand, and other countries have created game incubators, or they help game companies through tech incubators. In London, the Playhubs game incubator has some sweet space in central London, thanks to the government. London’s game industry is strong, but it still needs acceleration.

But Choudary said governments alone can’t create an industry. Incubators need mentors to train the next generation and give back to the industry. So you need successful game companies to spawn the next generation of successful game startups.

The U.S. has game accelerators like YetiZen, and tech incubators like TechStars or Y Combinator. But the tech incubators don’t do much with games, and their business model is to take an equity stake in their startups. By contrast, the incubators with government funding in other countries don’t take equity stakes. If we left it all up to the free market in the U.S., then the U.S. game startups would start out with a considerable disadvantage. Supercell didn’t have to give a stake to the Finnish government, and it later sold about half the company to Japan’s SoftBank for $1.5 billion.

I can see a lot of political reasons why the U.S. won’t act. Republicans could argue that government interference in the free market will just cause problems. They could say that the free market incubators will do the job much better than a government bureaucracy could. And Rhode Island’s $75 million loan to Curt Schilling’s 38 Studios, an ambitious fantasy game startup, ended in disaster, with politicians pointing fingers at each other about the loss for taxpayers. But we’ve got to get over our religious divisions in politics and accept some level of risk.

As far as the effectiveness of government intervention goes, I would point at China, where the government has ordered foreign companies to create joint ventures with domestic Chinese companies if they want to do business in China. There are a lot of problems with that, and it’s not a fair trade relationship in the big picture. But it has worked, as China’s giant gaming industry is on its way to be the world’s largest market with the world’s largest gaming companies. And if you haven’t noticed, China and other Asian companies are buying the game industry. Last year, the Corum Group said that nine of the top ten acquirers of game companies were Asian companies.

Finland, with a total of 2,600 game employees, is not going to overwhelm the U.S. But in China, I regularly discover game companies that I have never heard of before, and they tell me they’ve got 1,000 or more developers. China’s Tencent already owns big stakes in American companies like Activision, Riot Games, and Epic Games. I don’t want to sound alarmist about that. But when exactly should we become concerned about the growing foreign ownership of American game companies and the declining status of American games on the worldwide stage?

As for other concerns about government intervention, the creation of government-funded game incubators doesn’t crowd out private industry. Choudary said that her company would move upstream to concentrate on companies that have proven themselves in some way. I also call out Intel, which pledged to invest $300 million in the tech and game industries to support diversity. These game incubators could identify non-traditional talent and foster it, making game developers out of a more diverse set of people who wouldn’t otherwise make games. We definitely need more of that.

Like I said, inaction would be fine. There’s no crisis. We might get lucky. But I’m going to pull out my American flag and wave it. By investing in America’s game companies, we will create jobs here and preserve that uniquely American creativity that has dominated the game business for decades. If we don’t act, other countries will pull ahead. And that would be a shame.

I would love to hear feedback on the ideas in this column, and I plan to write about it more in the future.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More