This interview has major story spoilers.

Much like with BioShock Infinite, Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us has inspired a huge Internet discussion about morality of its ending. The game is burning up the charts and will likely be one of the most successful PlayStation 3 exclusive titles of all time.

We talked to Neil Druckmann, the creative director for the game at Naughty Dog, and director Bruce Straley about the striking differences between the cinematic beginning of The Last of Us and its understated, almost anticlimactic ending. They talked to us in a comprehensive wrap-up interview, and we’ve broken out this snippet about the comparison between the start and the finish of the game. Please leave your own comments and thoughts.

For the extended version of our interview (part one), please check out this link. And here is part two of our extended interview. And here is our excerpt on the female characters, our excerpt on gameplay decisions, and another excerpt on the inspirations for the game.

GamesBeat: The beginning of the game knocked me off my feet. It was very different in that you started out with the impact of this virus on everyone else. A typical zombie story or whatever, it seems like it would start out with an explanation of where the virus came from or something. You guys didn’t do any of that stuff. You just started with something weird happening in this town. Can you talk about that?

Bruce Straley: We didn’t want it to be about a government conspiracy. We didn’t want it to be about the backstory. It’s a game where you play as these two survivors making their way across a post-pandemic world. That’s our focus. Getting into all that other unwieldy exposition-y storytelling just gets in the way of what we’re trying to do.

Throughout production, Neil and I focused on how less is more. How do we strip down things to get to the core? How do we leave things to subtext? Specifically, using the video game medium for what you’re describing about how we started the game—It’s more intriguing to play through these events as they truly would happen to somebody, and not have the privileged knowledge about what’s on TV or how scientists have discovered this virus and how it spreads. It’s more interesting to see how it’s actually going to go down. It’s way more intense, because it leaves so much to your imagination.

The Hitchcock way of doing things is that you’re left to interpret it yourself, which is way worse than listening to somebody expound on how A matches with B and B equates to C. That’s not nearly as intriguing.

One other lesson learned is that you don’t have to show your whole game development. That was a success for us. We showed very little of the game and I think that paid off at the end. Going forward, I think we’ll keep doing that.

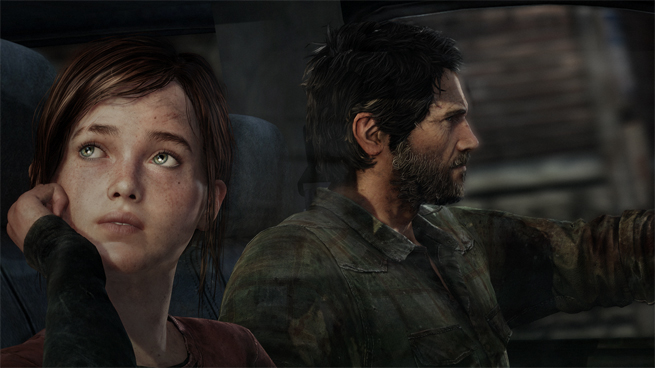

Neil Druckmann: The intro is about a family. That’s ultimately what the story is about. The opening shot of the game is Sarah and the closing shot is Ellie. That’s what the story is about, the bond with these two girls.

GamesBeat: That was one of my questions. What should the gamer remember about the beginning when they come upon the ending?

Druckmann: That’s an interesting one. There’s the question of what Joel has lost. The game explores this concept of a fate worse than death. If you turn into one of the infected and you’re still conscious, but lost in there, that’s a fate worse than death. Here’s this guy who’s lost his kid. That’s the worst fate for a parent. You’d rather die a hundred times than experience your child dying. And here he is at the end about to experience that again. How far is he willing to go to not have that happen?

GamesBeat: The first 15 minutes or so of the game, it was so beautiful. It was movie-like. The interesting comment is that for a lot of gamers, when you say a game is movie-like, it’s a negative thing. It means you have to watch it instead of playing it. How did you feel about that duality there?

Druckmann: Usually the word that’s used is “cinematic.” Some people see that as a pejorative for a game. We don’t. Steven Soderbergh gave a good talk about what it means to be cinematic. He talks about having authorial intent, using pacing, using lighting and shots. When we looked at the intro, the question was, “How do we set up the tension of the world?”

You gain control of Sarah. You’re walking out and turn the camera, and then you see light coming from Joel’s room. You start to hear this news report and you walk in. That seemed like about the right amount of time to pass to give you the next clue, so you hear the news report. Then you hear the explosion and the window rattling. We use sound effects to complement that. Then the music comes in when Joel runs into the house. It’s using all those storytelling elements that are usually attributed to cinema, but we’re using them in gameplay. To us it’s like, why wouldn’t you use that language? We’re a visual medium as well.

GamesBeat: When I wrote my own story about your game, I used a line from Schindler’s List: “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” I always thought that was a great quote. The game and the ending made me think about it. The funny thing about it is that’s not true in this case. You save a life and doom the whole world.

Druckmann: Well, you’re a parent. We’ve talked to people who’ve finished the game. A lot of articles refer to Joel as a monster at the end – “What does it feel like to play a monster?” Just as I don’t feel that Marlene is a monster for wanting to kill a kid to save mankind, I don’t view Joel as a monster either. How can you ask him to do that?

You can argue that maybe he goes too far. There’s a conversation to be had. But for him, well, you can survive. He’s survived for a year in this world. What is it worth saving mankind if he has to go through hell again?

GamesBeat: One interesting thing to me is that the other game that’s really resonated this year is BioShock Infinite. The ending of that game is something that people have talked about a lot, and it’s very similar with The Last of Us. The thing that’s gone viral, that everyone’s talking about, is the ending.

GamesBeat: One interesting thing to me is that the other game that’s really resonated this year is BioShock Infinite. The ending of that game is something that people have talked about a lot, and it’s very similar with The Last of Us. The thing that’s gone viral, that everyone’s talking about, is the ending.

Druckmann: That’s something that worked in our favor. We had focus tests at the office, where we brought people in to play the game, and for a long time, the ending tested badly. People felt it was unsatisfying. They wanted more of a climactic battle. They said that one of the characters should die, or maybe they both should die. Someone even suggested that Ellie shoot Joel at the end. But for us, we had this idea for the ending and we stuck to it. It felt like the most honest thing we could do for the characters.

Straley: With the example of BioShock, as well as our game—I played through BioShock, and there’s something to be said for not necessarily understanding exactly what’s going on. That helped me talk to people about it. There’s something about subtlety and ambiguity and subtext. When you see conversations between people out there and this stuff resonating with them, it gives us hope for the industry as a whole. Maybe people are maturing. We’re starting to look at them as an audience in the way that good filmmakers do, using subtlety and subtext in their filmmaking. It’s more interesting to let the viewer or the player figure things out for themselves.

We’re all grown up now. I’ve seen enough good stories in books and film. Now I want to see them in video games. When they come, that subtlety really sells. Now I can get in an interesting conversation with Neil about what this means over lunch or something. We find that more interesting, not only as developers but just as people who digest media.

Druckmann: It’s super intriguing to us, seeing all these articles that talk about whether Joel is a hero or a villain. Why does he have to be one or the other? Couldn’t he just be a complex person who’s made good and bad decisions? It’s open to interpretation.

Straley: It’s interesting, because it butts up against everything that you know about video games – the hero complex, the power fantasy, saving the world. If you just make deep characters that have real human drama, at this point in our lives and in the medium, it’s much more interesting to discover what we can do with story and gameplay and paralleling those two. I think there’s still so much more potential in this medium. We’re only scratching the surface.

GamesBeat: The interesting part about the movie side — toward the end Joel is in the hospital, and he’s trying to rescue Ellie. You have no choice left. You have to follow through, and you have to shoot these doctors. Can you talk about that? That part disturbed me. In effect, at that point, I didn’t have a choice in the game?

Druckmann: Just out of curiosity, what did you do when you got there?

GamesBeat: I just stood there for a while, waiting for Joel and Ellie to escape. Then I realized, “OK, it looks like I have to shoot these people in order to get Ellie out of there.” So I did. One of the workers was just sitting on the ground. I tried to shoot him in the leg, but he basically keeled over and died.

Druckmann: The one you have to shoot is the surgeon, the main guy with the scalpel. The other two, that’s just you being dark. [laughs] You don’t have to kill them. You could have just picked up Ellie. But that was intentional. That whole sequence used to be a cutscene, where Joel walks into the operating room and kills the doctor. But there was something, again, about using interactivity to say, “You are going to role-play as Joel. We’re going to make you feel that choice.”

Whether you agree with it or not, Joel is on this rampage. It’s ultimately his decision, but if you’re along with the story, you’re going to have to commit these acts. It rubbed some people the wrong way, that they didn’t have a choice, because – especially at the end of games – they’re so used to having this moral choice. But it didn’t feel honest to the character. It felt to us like if you were along for the ride, you were going to have a bitter experience, because you’re doing these acts yourself. You can feel horrible about them or question them or debate them, but you have to commit these acts if you want the story to progress.

Straley: People debate a couple of things. They say, “It’s an interactive medium. I want that choice at the end. I want engagement there.” First, it’s not a game built on that. The story hasn’t done that up to that point. It would feel very awkward to just throw that choice in at the end. Second, when we asked people, “Okay, if we did give you that choice, what choice would you make?” 90 percent of them said, “I’d save Ellie, of course.”

Some interesting articles have come out recently about empathy games, and then some about the end of our game. It’s the contrast of the conflicts between what the player is thinking versus what Joel is thinking that allows you to explore what we’re doing with that character. It’s because you’re not him that you get to see him.

I find that interesting as a device. It’s not about interactivity or non-interactivity. It’s being able to explore something that you are not. It’s Joel who’s going through that, not you, but you get to feel some of what it’s like to be Joel and what lengths Joel is willing to go to.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More